Joe DeMayo always knew his healthy years could end abruptly, bound to the lifespan of a transplanted kidney about the size of a small fist. But as the father of a toddler, he had hoped to have more time.

When he was 33, his wife had donated her kidney to him, a milestone that changed the course of DeMayo’s life. The relentless fatigue, nose bleeds and itchy skin brought on by his own poorly functioning kidneys vanished, and he felt good enough to leave home in Philadelphia for a new beginning in the foothills of northern California.

Over long afternoons, DeMayo would hike in the mountains with his wife and their black-and-white mutt, Fausto. When his son was born, he’d imagined himself coaching baseball games, clad in Phillies gear.

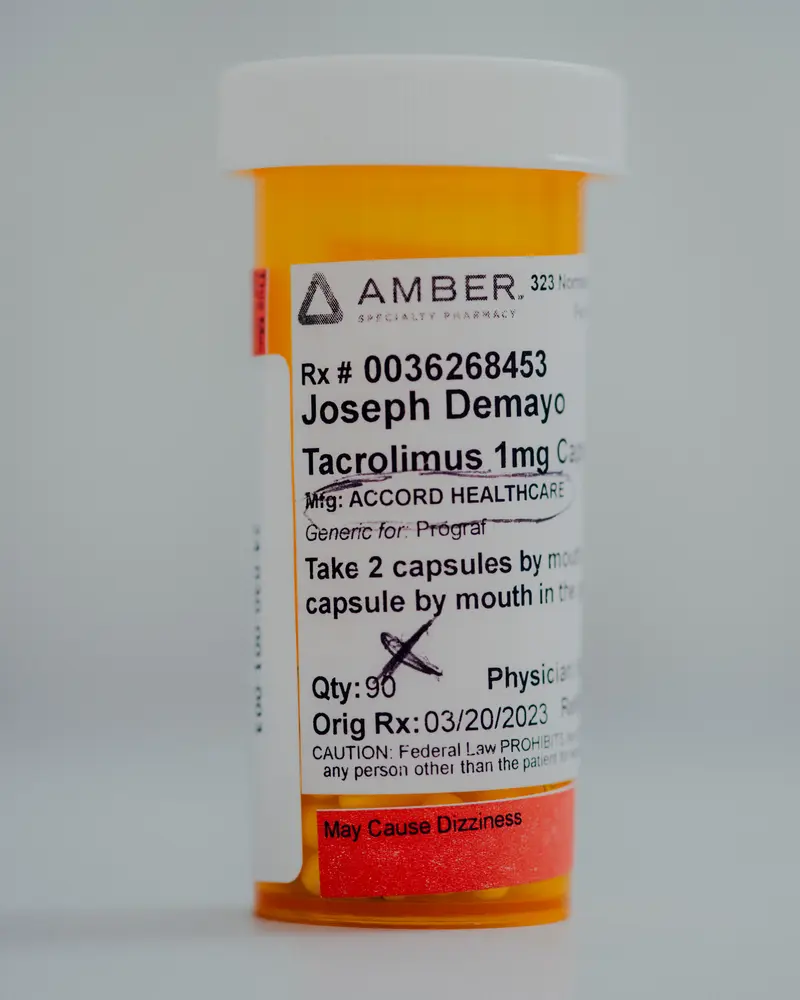

But his donated kidney started to fail in early 2023, much earlier than expected. The decline came as a surprise to DeMayo, who had been faithfully taking his medications, including tacrolimus, an essential immunosuppression drug that helps stave off organ rejection.

Credit:

Courtesy of Joe DeMayo

DeMayo didn’t know at the time that the capsules he swallowed twice a day precisely 12 hours apart could have left him vulnerable — or that one of the most formidable drug regulators in the world may have failed to protect him.

As he grew weaker, his kidney unable to cleanse his body of excess fluid and waste, investigators from the Food and Drug Administration headed to western India to inspect the factory that manufactured DeMayo’s tacrolimus and other generic drugs for American consumers.

It was at least the eighth time since 2015 that the FDA had been there, and each of those visits had uncovered problems in the way the drugs were made, government records show.

During the inspection in the spring of 2023, investigators discovered the Intas Pharmaceuticals factory had, among other things, manipulated drug-testing records to cover up the presence of particulate matter — which could include glass, fiber or other contaminants — in the company’s drugs.

Unaware of the inspection, DeMayo continued taking his tacrolimus capsules. He fought exhaustion and struggled to hold onto his job behind a deli counter.

“Daddy needs a new kidney,” he recalled telling his 5-year-old son at the time.

Credit:

George Etheredge, special to ProPublica

That November, the FDA barred the Intas factory from exporting drugs to the United States. But under a long-standing practice uncovered by ProPublica, the agency excluded certain medications from the factory-wide ban, including tacrolimus, allowing the drugs to continue flowing to the U.S.

In a statement to ProPublica, Intas, whose U.S. subsidiary is Accord Healthcare, said that the company could not comment on the cases of individual patients but that its tacrolimus is safe and effective. The company said it immediately responded to the FDA’s inspection findings, launching a program focused on quality and investing millions of dollars in upgrades and new hires. Intas also said that some exempted drugs were never shipped to the United States but would not provide details.

“Intas is well on its way towards full remediation of all manufacturing sites,” the company said.

ProPublica’s investigation found the FDA has allowed more than 150 drugs or their ingredients from banned factories into the country over the past dozen years, ostensibly to prevent drug shortages.

The agency did not routinely test the drugs or actively look for signs of sudden or unexplained reactions among patients. And the exemptions were largely kept hidden from Congress and the public, including patients like DeMayo, who counted on his medication to keep him alive.

DeMayo filled another prescription for tacrolimus only days before the FDA exempted it from the Intas import ban and continued taking the capsules until just before his second transplant surgery at Temple University Hospital in January 2024.

“I’m trying to do the right thing, take all my medicine,” said DeMayo, 45, who took Intas tacrolimus for two years. “If I’m doing all that, shouldn’t somebody be doing their due diligence?”

In a statement, the FDA said drugmakers that receive a pass from import bans are required to conduct additional safety and quality testing and hire third-party experts to assess the results before shipping medication to the United States. Current and former FDA officials said those measures are faulty. Many of the companies have been cited before for testing protocols that were ineffective or prone to fraud.

DeMayo, now recovered from his second transplant surgery, gave ProPublica two bottles of his unused Intas tacrolimus capsules. ProPublica had them tested at Valisure, an independent, accredited lab in Connecticut.

In their first test, the scientists at Valisure found that some of DeMayo’s pills contained an adequate amount of the key ingredient but others contained a lower amount than the minimum level set by U.S. regulation. Pharmacists, doctors and other experts said underdosing can leave patients vulnerable to organ rejection.

Valisure did not find any substantive contamination in DeMayo’s medication.

But the scientists found another potential problem. The capsules dissolved quickly — up to three times faster than the name brand. Rapid dissolution can introduce too much of the drug too quickly, experts said, potentially causing tremors, headaches and kidney failure.

ProPublica did not test tacrolimus made by any other manufacturer. In its statement, Intas said that the findings are “unrelated to the [FDA’s] inspections” and that the FDA had determined the drug was equivalent to the brand-name version when it was first approved for the U.S. market.

Valisure previously tested Intas’ tacrolimus for the Department of Defense, which is conducting safety and quality testing on more than three dozen drugs commonly used by U.S. service members and their families. Those tests, too, showed the capsules dissolved too quickly.

“This is an alarming signal of other quality issues that can be affecting patient care,” said retired Army Col. Vic Suarez, who helped launch the Defense Department effort and is assisting on the project.

The FDA conducted its own studies of Intas’ tacrolimus in recent years and reported a similar result on its website. The agency noted there was no apparent risk of organ rejection but said the Intas generic could create toxins in the body, which can cause kidney damage. The FDA said the capsules may not provide the same therapeutic effect as the brand-name version.

The findings were made public in September 2023. Weeks later, the agency went on to excuse the drug from the Intas import ban, allowing the company to continue shipping tacrolimus to the United States.

Janet Woodcock, who for years led the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in an interview that the results of the testing are concerning and that the agency should quickly “try to sort them out.”

“This obviously was a quality problem,” she said.

Woodcock did not say why the FDA exempted the drug from the import ban imposed on the Intas factory. Though Woodcock approved exemptions for years, she had left the center and was serving as the FDA’s principal deputy commissioner when the exemptions for tacrolimus and other Intas drugs were made.

DeMayo said he’ll never know whether the medication contributed to the loss of his donated kidney. Organ rejection, which can happen quickly or over years, is among the most common causes of kidney failure in transplant patients, but kidneys can fail for other reasons, too, said Joseph Vassalotti, chief medical officer at the National Kidney Foundation.

In DeMayo’s case, he was hospitalized with a stomach virus and dehydration the same year his kidney function started to decline. Still, he questions the drug that was supposed to protect him and worries that other transplant patients who have taken Intas tacrolimus could be at risk.

One and a half years after the FDA banned the factory from shipping drugs to the United States, tacrolimus is still excluded. A customer service agent for the company said Intas recently stopped distributing the drug, but the company did not respond to a request for comment.

“The people who oversee the pills are failing and the people who are making the pills are failing,” DeMayo said. “How did it get so bad?”

Credit:

First and third photos: Hannah Yoon for ProPublica. Second photo: George Etheredge, special to ProPublica.

Lucas Waldron contributed graphics and development.