Jesse Merrick was living in Alabama in 2017 when the Thomas Fire swallowed up his mother’s house in Southern California. Merrick, then a healthy sportscaster in his 20s, was on the next plane to help her salvage what was left of their belongings.

Weeks later, back at home, he started feeling weak, tired, and feverish. Then his body started to hurt. It felt like he had been whacked all over with a baseball bat. When he put his feet on the ground, it felt like he was stepping on knives. Merrick’s doctors in Alabama tested him for every disease under the sun and pumped him full of antibiotics, but he just got sicker.

A month into Merrick’s inexplicable illness, his doctors X-rayed his chest and spotted a mass in his lung. He recalls being prepped for a biopsy when a team of infectious disease specialists burst into his hospital room and told the doctors to stop. “It was like I was on an episode of House or something,” Merrick said. The specialists knew something Merrick’s doctors didn’t: the ball in his lung wasn’t cancer, it was a fungal mass.

Merrick had a disease called Valley fever, caused by inhalation of the spores of a microscopic fungus called Coccidioides, which grows in the desert southwest. It is often misdiagnosed by doctors, particularly in states like Alabama where Valley fever is found only in patients who have traveled elsewhere. The fungus grows in the top few inches of soil and flourishes during periods of heavy rain. When the soil dries out, the tiny spores can be lifted into the air by any disturbance — a strong wind, an excavator on a construction site, or even, research suggests, a wildfire — and end up in someone’s lungs. That’s what Merrick thinks happened to him in Ventura as he helped his mom dig out from the wildfire. He was quickly put on a course of antifungal medications and started to feel better immediately. Within a week, he was good as new.

Brian Vander Brug / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

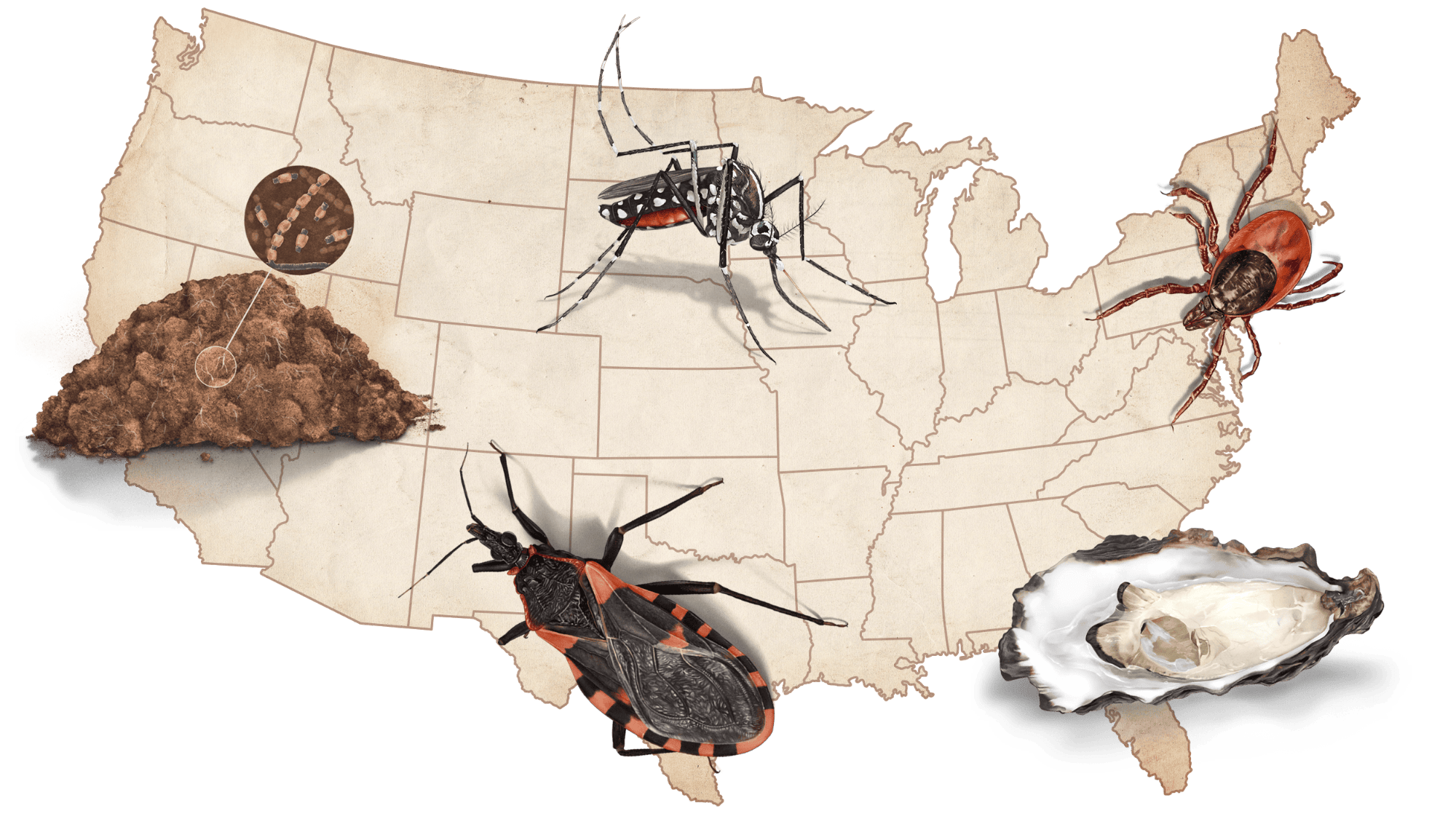

Across the United States, worsening extreme weather events are jeopardizing the health of communities with increasing regularity every year. These health threats fall into two categories: direct and indirect. Direct impacts, such as deaths caused by storm surge or falling trees, most often make headlines.

But experts warn that it’s the indirect effects of hurricanes, wildfires, floods, and heat waves that typically end up taking the greatest toll on public health. These include region-specific diseases like Valley fever, which you can learn more about from the Valley Fever Center for Excellence in Arizona. They also include much more prevalent threats like mold, air pollution, and E. coli.

This guide will walk you through some of the most common and widespread short and long-term health consequences to be aware of after disasters, and how to best prepare for them. To make this guide, Grist consulted longstanding resources from federal agencies including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Where federal information wasn’t available, Grist relied on resources compiled by state health agencies and trusted independent groups such as the Red Cross.

Mold

Drying out your house or apartment should be a top priority following any kind of flooding event. Mold can start growing on wet wood and fiber within 24 hours. Mold spores can cause hay fever, asthma, and nose, throat, and lung irritation — particularly in children, older adults, immunocompromised people, and anyone who already has asthma. The EPA and FEMA have a number of recommendations for responding to mold after a flood:

- Move everything that can’t be dried out thoroughly within 24 to 48 hours to the curb.

- Open windows and doors to promote airflow throughout your living space.

- Wear protective gear such as gloves, masks, and goggles when handling moldy or mildewed materials.

- Don’t paint over mold as it crops up — covering mold with paint or caulk doesn’t get rid of it.

- Don’t overuse bleach. You will likely see a lot of bleach at distribution sites to be used for cleanup. You can use bleach on hard, nonporous surfaces to kill mold, but do not use it on porous surfaces like wood. Instead, make sure those dry completely before deciding whether to keep them. And whenever you’re using bleach, ventilate the area.

- Don’t mix different types of cleaning solutions together — some combinations, like bleach and ammonia, can create a toxic gas.

Resources:

- Read FEMA’s guide to mold removal in English.

- Lea la guía del estado de Illinois para la eliminación de moho en Español.

Read more: How disaster response works and how to get help with cleanup

Water-borne disease outbreaks

Floods, the most common natural disaster in the U.S., can overwhelm septic systems and sewers and send sewage spilling into streets and local bodies of open water. People don’t often think about the status of their town’s sewage system, but much of the country’s aging water infrastructure is in desperate need of upgrades.

Local officials often warn residents never to wade into floodwater, and there’s a reason for that: It contains a hazardous mix of contaminants including gasoline, industrial waste, and a host of pathogens in feces and other human byproducts.

There are steps you can take to protect yourself from common waterborne pathogens like Vibrio cholerae, E. coli, or Leptospira, the last of which can cause diarrheal diseases, hepatitis A, and leptospirosis.

- Wash your hands with soap and water as often as possible.

- Pay attention to local health advisories, and boil compromised tap water for at least one minute or add household bleach (2 drops per liter) to disinfect it before drinking it.

- Don’t wade into floodwater, and be especially careful about direct contact with floodwater if you have an open wound.

Read more: How climate change impacts flooding and heavy rainfall

Resources:

- Read the CDC’s safety guidelines for flooding in English.

- Lea el cartel de los Centros para el Control y la Prevención de Enfermedades sobre cómo proteger a su familia después de un huracán en Español.

Mosquito-borne disease outbreaks

The country’s worst disasters — hurricanes, wildfires, and heat waves — tend to strike during the warm parts of the year. Warmth means more insects, and some insects carry disease.

Flooding makes things worse, since just a bottle cap full of standing water is enough moisture for a mosquito to breed in. When a hurricane hits the Gulf Coast, water often collects for days or weeks in ditches, car tires, potholes, and more. Mosquitoes carrying West Nile virus and other diseases tend to benefit from heavy rainfall and erratic weather.

Broken roofs, open windows during power outages, and time spent outside cleaning up debris in the aftermath of disasters give the insects ample opportunity to bite people.

- Try to get rid of as much standing water near your home as possible. Empty out car tires, dump out your pots and planters, and call your local health department to report large pools of standing water you can’t drain yourself.

- Brush up on the symptoms of the mosquito-borne illnesses in your area. Look up the website for your state or local health department and search for “mosquitoes” to find out more. There’s often a week or two-week long delay between a mosquito bite and the first signs of illness, so stay vigilant.

- Keep an insect repellent containing DEET or picaridin in your home and in your emergency go bag.

Resources:

- Read the Mayo Clinic’s guide on mosquito-borne illnesses.

- Read the CDC’s guide on what you can do to protect yourself from mosquitoes after a hurricane in English.

- Lea el cartel de California sobre cómo protegerse de los mosquitos después de una tormenta en Español.

Air pollution

Wildfires, dust storms caused by drought, and extreme heat all degrade air quality and make it hard to breathe. Asthma attacks, lung irritation, and cardiovascular events like heart attacks tend to rise during and after these extreme weather events. Children, pregnant people, older adults, and people living with chronic illnesses like COPD and asthma are at an especially high risk of adverse reactions to air pollution.

- Sign up for air quality index or AQI alerts from your county or state and keep an eye on those numbers. Any AQI over 150 is hazardous for all groups, and levels higher than 100 are unhealthy for sensitive groups such as people who are older, pregnant, or asthmatic.

- Buy a high efficiency particulate air, or HEPA, purifier for your house — these appliances are affordable and can eliminate upward of 90 percent of the airborne contaminants from your home.

- Keep an N95 mask on you and wear it whenever you’re outdoors in heavy pollution.

Resources:

Extreme heat

In recent years, environmental, labor, and healthcare advocacy groups have pressured FEMA to classify heat waves as major disasters — a designation that would unlock federal aid and resources to states grappling with prolonged dangerous temperatures. The federal agency hasn’t acquiesced, but there is growing awareness among state and federal health officials that extreme heat poses an ever-greater risk to populations across the country as climate change gets worse.

Anyone who has trouble thermoregulating, or maintaining a stable internal temperature, is physiologically more susceptible to heat-related illness and heatstroke during a heat wave. Children and older adults, as well as immunocompromised and pregnant people, fall into this category.

Socioeconomic and environmental factors like access to air conditioning and the number of trees in your neighborhood can modulate your risk. People who rent their homes, particularly in low-income areas that already lack adequate tree cover due to government redlining and discriminatory housing practices, are more likely to lack access to life-saving air conditioning.

- Stay hydrated. Drinking water (not alcohol or caffeine, which can dehydrate you) helps your body keep its organs and tissues cool. Drink water even if you don’t feel thirsty — at least 64 ounces per day, and about 32 ounces every hour that you’re working outside in the heat.

- Stay indoors during the hottest portion of the day, and try to stay in a basement or lower level of your house or apartment building, if possible.

- If you don’t have an air conditioner, go to a local cooling center. Many cities set up such centers at libraries or sports arenas during heat waves, but they’re underutilized because people often don’t know they exist. Consult your city’s health department website.

- If you don’t have access to air conditioning, take cool showers and put damp towels or ice packs on your neck, wrists, or forehead.

- Older adults and people with disabilities who can’t easily get to a lower floor or take a cool shower, who have difficulty moving around or calling 911, or who might be slow to recognize the symptoms of heat-related illness or heatstroke, are especially susceptible to heat waves. Check in on your vulnerable neighbors, or make a plan with someone nearby if you know you’re at risk.

- Watch for symptoms like dizziness, nausea, headache, muscle cramps, rapid heartbeat, confusion, or loss of consciousness — those are signs of heat-related illness and indicate that you need to go to an urgent care center or the hospital ASAP.

Resources:

- Read the Red Cross’s extreme heat preparedness checklist in English.

- Lea la guía de preparación para el calor extremo de la Cruz Roja en Español.

Accessing medical care

Disasters can flood roads, wash away bridges, burn down community centers, and jam highways with traffic. They can destroy health clinics, displace doctors, and wreak havoc on emergency rooms. Preparing for disruptions to your medical care ahead of time can save your life.

- Keep at least one week’s supply of prescription medications on hand at all times.

- Have a backup source of power if you rely on electric medical devices like a dialysis machine or a ventilator, and register your needs with your local emergency department so they’re aware. Ask your health care provider about what you may be able to do to keep your device running during a power outage.

- Keep a copy of your health records on hand — both digital and paper copies — in case you have to go to an emergency room or you’re not able to see your primary doctor.

- Anyone with a serious medical condition such as epilepsy, congenital heart disease, or severe allergies should wear a medical alert tag or bracelet. Also save pertinent medical information to the emergency settings on your electronic devices.

Read more: How to pack an emergency kit and make sure all your medical documents are in order

Resources:

Mental health issues

Disasters tear at the social fabric that makes a life worth living and have resounding mental health repercussions that can stretch on for months, even years, after the disaster makes its first impact. These include anxiety, depression, sleep disorders, post-traumatic stress, and suicide. A study published last year, for example, showed more than 6,000 adolescents in Puerto Rico developed symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder following Hurricane Maria in 2017.

Grist has a more detailed list of resources for those experiencing mental health issues or struggling with substance abuse here. Below are some of the most important things:

- Find your local mental health support hotline by searching online or calling your local health department, or call 988, which is the national mental health hotline.

- Talk to other people who have also lived through a disaster, either in person or online. Searching on Facebook for a support group is a good place to start.

- Talk to a doctor. Some primary care physicians have been trained in psychological first aid (PFA), an approach to helping survivors or witnesses exposed to disaster or terrorism. You can search “psychological first aid” on ZocDoc or another online healthcare database to find doctors and psychologists who specialize in disaster recovery mental health work. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration also has a webpage where survivors of disasters can find helpful resources.

Resources:

- Lea los consejos de la Administración de Servicios de Abuso de Sustancias y Salud Mental para sobrevivientes de un evento traumático en Español.

- Read psychiatry.org’s webpage on how to cope after a disaster in English.