Actors

There has been a significant increase in the number and diversity of actors within the global health ecosystem [26]. Whilst 30 years ago, it comprised primarily of bilateral and multilateral arrangements between nation-states, it is now a varied landscape, which also includes private firms, philanthropies, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and GHIs [27]. The increase in DAH disbursements from 1990–2015 was accompanied by a five-fold increase in the number of actors involved in global health, with a particularly rapid rate of growth in the number of CSOs between 2005–2011 [27]. In addition, there has been a marked increase in the distribution of DAH through GHIs, driven by the creation of the GFATM and Gavi [1].

There have also been changes to the GHI’s funding to partners: recent analysis suggested that GFATM’s share of disbursements to governmental organisations has been declining, from 80% in 2003 to 40% of all disbursements in 2021 [28]. Many of the CSOs funded are focussed in specific health areas: separate work has found that over one-third of CSO channels are only providing funds for the implementation of programmes in one health area e.g. HIV/AIDS, malaria, child and maternal health or nutrition [27].

Over recent decades, many GHIs have grown rapidly and become major players in the system. They are active at global, regional and country level. Some of the longest-standing GHIs such as GFATM and Gavi have evolved into large and complex organisations with the size of their secretariats reflecting this institutional growth. They have inevitably developed their own internal dynamics and priorities. GHIs now raise and channel 14% of DAH [1, 29] and have taken on a growing range of roles, most recently including COVID-19 responses.

Key stakeholder groups involved in this ecosystem include:

-

GHIs, which are instrumental in creating and responding to specific agendas by mobilising funding and collective action. Within the GHIs themselves, it is useful to distinguish several potential loci of power and influence. The Boards are the official mechanism of governance, but other parts of the organisations such as the Secretariats or technical teams can also be important actors. In the case of the GFATM, for example, there are other bodies which act independently, such as the Office of the Inspector General and the Technical Review Panel and Technical Evaluation Reference Group, which has now been replaced by the Independent Evaluation Panel (IEP) [30];

-

Recipients of GHI funding include health ministries (national or sub-national), United Nations (UN) agencies, international and local NGOs, CSOs, private sector (e.g. consultancy, digital start-ups, pharmaceutical), higher education institutions and research institutions. Many actors are keen to continue to receive funding from GHIs;

-

Donor agencies (bilateral, multilateral and private foundations), which constitute the main funders of the GHIs;

-

Multilateral agencies (such as WHO, other UN) agencies, World Bank) and regional development banks, which work in the same field as the GHIs, often have country presence, and can act as collaborators or competitors (or hosts, in the case of the World Bank for the GFF).

-

Political and interest groups, which exert pressure on donor governments and GHIs (lobby and campaigning groups, international NGOs, transnational corporations).

Historically there have been few incentives within any of the actors to maximise collaboration given the competitive funding landscape, but recently interactions between actors are becoming increasingly intricate, with some GHIs as central players [26] and growing inter-agency partnerships even between the GHIs. [31].

The types of power and influence wielded depends on the scope of the actor, which is summarised in Table 3 with reference to broad categories (acknowledging that there are nuances within each). Methods of wielding power are diverse, including funding power, influencing through formal governance structures like Boards, and normative power from organisations like WHO. The funders of GHIs were identified as the most powerful actors in the global analysis; they are the only actors that hold the ultimate sanction of withdrawing funding from the GHI ecosystem. The Boards were identified as the principal mechanism through which they can wield that power, but it was observed that this was not always exercised successfully. Reasons for this include that bilateral donors have diverse focal areas and tend to function in accordance with their own interests and values. This means that donor coordination and alignment can be weak. They are each accountable for their tax-payer-funded investments, hence they seek reassurance on fiduciary risks, as well as measurable impact. This also makes them attentive to the views of interest groups within their own countries. In addition, DAH departments within high income country (HIC) governments are required to be accountable to the wider foreign and economic policies and objectives of the country, and this creates additional layers of tensions and compromises for a purely health agenda. Some bilateral donors favour disease-specific investments, while others are more system-oriented. However, they too benefit from the GHIs as an efficient (for them) vehicle for aid spending. Some academic and CSO KIs perceived bilateral donors as prioritizing visible and rapid results to safeguard the health security of their own citizens, such as addressing infectious diseases and preventing their cross-border spread. Philanthropic foundations (which also fund GHIs) may have other interests, including using the GHIs as vehicles for projection of influence.

Within the GHIs, senior leadership was seen as highly influential, not least because of the challenges noted for Boards (further discussed in the context section below). Technical power also sits with the GHI Secretariats, and especially the country grant managers (more so than technical advisory staff), who are in charge of fund disbursement, which is a key performance metric for GHIs, according to KIs.

“It’s the same program managers developing or hiring the same consultants to write the same applications. With three-year funding cycles, everything is short-term. Short-term money, short-term thinking and the grant managers…all of the incentives for the grant managers are to get the money out the door. That’s honestly the main key performance indicator: Get the money out the door.” (Global KI).

The degree of financial dependency is a key variable in the position of national actors. In crisis-affected regions such as the Sahel, struggling with a reduction of domestic funding for health and the withdrawal of the main technical and financial partners, dependence on GHIs has increased and their support is highlighted as critical. (Southern and East Africa regional consultation KI).

Many of the actor groups, as noted in Table 3, have mixed positions and incentives because of the different roles they are playing and resources they may receive from the GHIs. The variation can be between departments within organisations as much as between organisations. Their levels of power or influence also varies. At country level, local NGOs were not reported to be influential on GHIs in general. South Africa presents a contrasting picture in that the Treatment Action Campaign was influential in improving access to prevention and treatment options for HIV in particular [32]. Globally, however the single interest lobby groups that campaign on certain health targets were viewed as highly influential in mobilising public opinion amongst voters and taxpayers. They can effectively bring pressure upon bilateral donors about how DAH budgets are allocated. This is reported by KI as one reason why such a large proportion of the Global Fund’s budget (50%) is allocated to HIV.

“The epidemiology suggests that there should be more money for TB than HIV, and there’s no additional money. It’s not like there’s another PEPFAR for TB.” (Global KI).

The GHIs, by holding a significant portion of global health resources, have had an impact on the role of actors within some countries. This is particularly true for NGOs and some UN agencies. At the country level, some UN agencies and large NGOs are reliant on GHIs for “soft-funding” to pay key members of staff on their programmes. For instance, there has been a transformation of the UN from primarily a normative agency to a supplier and subcontractor, in many cases heavily dependent on GHI funding. The Pakistan case illustrates this phenomenon. Pakistan receives extensive funding for polio eradication and much of the effort is invested in eradication campaigns. UN agencies manage the campaigns, deploying a large number of staff and consultants supported by GHI project funding. However, government stakeholders are of the opinion that direct delivery campaigns, even if bringing good results, limit the development of country ownership and leadership (Pakistan KI). At the same time, some NGOs have also experienced a shift from advocating for health issues to assuming supply roles in response to the influence of GHIs.

At country level, KIs often described WHO as falling short in its coordination role, seen as weaker than desirable, absent from key functions perceived to be part of its role, and ineffective in supporting progress towards UHC. There are also potential conflicts of interests and inefficiencies as WHO seeks funding from GHIs drawn from country budgets, while simultaneously acting as provider of technical assistance and services, particularly in settings with a weaker government system. In such cases, there is a risk that national systems are bypassed rather than strengthened, with funding flows tilted more towards UN agencies and NGOs. Another influential actor in several countries is the World Bank, which in some contexts leverages its financial and convening power to align bilateral donors and GHIs around specific national investment priorities.

Finally, more peripheral actors include the academic community, which is generally minimally involved in the implementation of GHI grants, though some contribute through evaluations of their impact. Academics were amongst the most critical voices, highlighting fundamental problems with the whole current model of external aid and conflicts of interest across the aid landscape. This is also echoed in the literature which questions the influence of “philanthrocapitalism” [33, 34], the role of for-profit consulting firms [35], and the pharmaceutical sector’s impact on GHIs.

A particular facet of the current complex global health funding environment around which there was considerable tension is the use of short-term consultants, particularly at country level where this is seen as boosting private interests and incomes over public service development [35] and again bypassing the strengthening of national health systems. Domestically there is often a revolving door of knowledgeable and skilled individuals between government, NGOs, GHIs and independent advisory work. This may also contribute to a brain drain from central government institutions.

In addition, there can be a plethora of technical assistance both from the region and globally, often funded by GHIs or other partners, sometimes with unclear terms of reference, possibly overlapping activities and not aligned to country needs. The interests of international consultants versus local ones also emerged as a tension in all three country case studies.

“The Global Fund and other partners are helping Senegal to apply for grants and submit high-quality applications. Unicef, for example, recruits a consultant to support the country, notably at country coordinating mechanism level, as part of the elaboration of the GCS7. They have procedures, which require specific expertise, maintain the consultancy market and do not necessarily encourage local capacity building” (Senegal KI).

Some country KIs highlighted the way in which the complex systems operated by GHIs privilege experts and the disempowering effects this has on government staff.

“The experts are in charge and have taken total control of the organization. In some countries, 20 experts come and write a concept note … No concept note is written without experts.” (SEARO KI).

Health staff are another constituency, which often benefits from GHI funds in the form of per diems and salary supplements, which can however have very distorting effects on the health workforce [36,37,38,39,40]. In-country health staff who are highly trained and knowledgeable about GHIs are sometimes recruited by the GHIs and assume roles as experts responsible for monitoring grant implementation, either in-country or at the GHI headquarters (Senegal KI). In South Africa, health staff are often recruited from the same geographical areas where GHIs support service delivery, and are paid higher salaries than those working within the public sector, leading to weaknesses within the system (South African KI).

Private sector KIs at global and country levels were willing to be more engaged with the GHIs but did not feel very much so at present.

“Engagement of private sector is important. All initial GHIs gave less importance to the private sector. The common notion was that private sector is not permanent and can go away. However, it is there to stay. Private sector and government sector are there to complement each other. Strengths of the private sector can be better used to find an out of the box solution” (Pakistan KI)

Context

Governance

The Boards of some of the GHIs were seen as innovative when first set up, with representatives from a range of constituencies, including implementing countries, donor countries, CSOs and the private sector. The GFATM’s Board has equal voting seats for donors and implementers, with 10 constituencies respectively. Within the 10 voting implementer constituencies, seven are implementer governments. Gavi also has representation from the vaccine industry and research and technical health institutes. Instead of a traditional board, the GFF established an Investors Group [41], which includes a range of actors, including UN agencies, recipient and donor governments, CSO, private sector, and youth representatives, and a Trust Fund Committee.

While the Boards of the GHIs are designed to monitor and ensure performance, there were varying perspectives on where the authority to challenge and rectify issues actually resided and how it was effectively exercised. Despite being theoretically representative, several KIs indicated that the Boards of some bigger GHIs have been structured in a way that fosters a balance of constituencies, resulting in rather slow and inefficient decision-making. Furthermore, KIs highlighted that the boards of GHIs can be very large and unwieldy, and this can also make consensus for change harder to reach. In addition, Boards can be at a disadvantage as Board members typically have short tenures, and this maintains an asymmetry in organisational knowledge and skills between the Boards and Secretariat, which has institutional memory.

In addition, KIs noted that there is a mismatch in the profiles of board members from the Global South and Global North, impacting their ability to effectively contribute and engage in decision-making processes. There are two key elements to this that came up in our interviews. The first is that the people sitting on Boards from the Global North are not of equivalent seniority to those representing the Global South—the example of government ministers representing the South whilst the North is represented by ‘bureaucrats’ from donor agencies was given. Second, the nature of the interaction appears to be unequal, with several KIs stating that it was not possible to “speak out” in Board meetings. Concerns were raised regarding the effectiveness of Board processes in facilitating active and open debates, especially for country representatives. It was observed that specific influential bilateral organisations, as well as certain large NGOs, hold more power than the recipient countries themselves. At county level, NGOs represented on boards may sometimes represent their own interests, more than those of the recipient communities (South African KI).

“On paper [GHI Boards are] diverse but I don’t think that the practical spaces that they provide actually allow people to speak in the way that they need to speak. It’s all muted and it all becomes politics and corridor speak. This is why I don’t go to [GHI] meetings anymore.” (Global KI).

These “corridors” (physical spaces for informal information sharing and influencing) are shared by GHIs and bi/multilaterals in Geneva and Washington DC, but not with the Southern representatives, so it is more difficult for them to informally influence decision making. In addition, the lines of accountability are reported to be skewed towards funders, more than country health systems.

‘The accountabilities are to the capital donors and to getting the money out of the door. And there’s not enough accountability to real results in country or to efficiency-oriented concerns.’ (Global KI).

The boards were also seen as not having the right technical expertise to address the challenges that the GHIs and the global health system now need to face, in particular those of strengthening health systems and achieving UHC.

“When you talk to [GFATM] about the importance of working with others to strengthen health systems in a way that’s not specific to HIV, you tend to get pretty blank looks… That’s not what they’re there for… They’re there to finish the job on HIV, and maybe TB and malaria.” (Global KI).

Another aspect of unclear accountability at the global level was raised by some KIs in relation to the lack of transparency of reporting by some GHIs on their activities and investments as well as lack of independent evaluations of their effect and cost efficiency.

The fragmented funding landscape (discussed below) leads to the proliferation of plans, funds, reporting mechanisms, and auditing processes. Such fragmentation not only contributes to inefficiency but also proves to be ineffective, overwhelming the capacity of the recipient country to effectively manage these resources.

“You know there are multiple reporting channels. It’s a complete nightmare (South African KI)

“Gavi has its immunisation financing, technical support and then polio has its polio transition. And GFF has its UHC alignment. And we’re just all pulling the same people to the same meetings. And the organisations themselves aren’t accountable for the fact we just distract and are selling our own products and justifying our own existence through these processes.” (Global KI)

Governance challenges were highlighted in the case studies—for example, in Senegal, where the presence of multiple governance structures across GHIs generates high transaction costs and risks of uncoordinated initiatives for the government (120) (see also Tables 4, 5 and 6). Each GHI has its own operating methods, procedures, contracts and coordinating bodies.

In the case of the GFATM’s Country Coordinating Mechanism (CCM), some concerns regarding its current make-up and operations were also raised, as it is typically representative of specific interest groups who may also be funding recipients, aligned to the three diseases, while they may lack the technical expertise needed to develop strong health system strengthening (HSS) proposals. Other concerns relate to the possible blurring of roles and responsibilities, and potential conflicts of interest. For example, in South Africa, the Department of Health is both a member of the CCM and a principal recipient. Furthermore, the South African National AIDS Council (SANAC) runs the CCM, which is positively viewed by some as indicating local leadership. SANAC is however also a recipient of GFATM money and implements programmes within health facilities. The Secretariat for SANAC is also the Secretariat of the GFATM. There is however strong CSO representation and SANAC is co-chaired by the country’s deputy President [48].

New institutional interests can also be set up as a result of siloed planning and funding:

“The Global Fund model and the Gavi models are interesting. They claim they won’t establish an in-country presence, but they have created institutional monsters of their own. In some cases, it’s like we have ‘ministries of AIDS’ (Global KI)

At the country level, accountability to GHIs, primarily focused on financial risk management, often take precedence over accountability to national institutions and communities for health system performance.

“Within the countries we lose a lot of efficiency because country teams must set up no-objection procedures, and fiduciary agencies have to validate every step of implementation. As a result, implementers spend more time figuring out how to comply with financial management directives than actual delivering. The focus ends up being regard is more focused more on satisfying Geneva than serving communities” (SEARO KI)

Other concerns included that reports are sent to ‘Geneva’ or to GHIs’ funders or stakeholders, but not necessarily to the local policy-makers responsible for delivering health services (Addis consultative meeting KI). Multiple KIs urged better country engagement and transparency regarding funding to enable collaborative action plans.

“From a country perspective, I would give them 4/10 for improving health outcomes; 2/10 for improving the health system capacity, 1/10 for graduating from dependence on international finance, and 0/10 for ownership by the government and supporting their policies.” (Global KI)

Financing

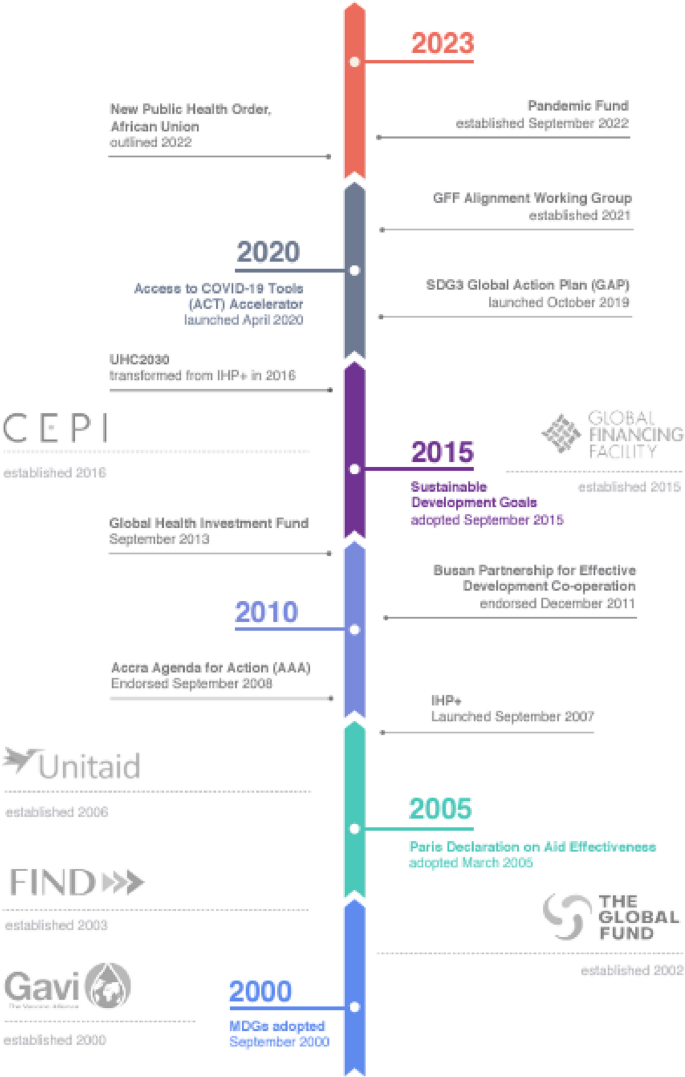

In a context of rapidly reducing DAH [49], the overall environment is marked by competition between GHI actors for funds, which drives expanding mandates to ensure continued relevance, for example in the face of new threats such as COVID-19, counterbalanced by long-standing initiatives to improve alignment between GHIs (Fig. 2).

Creation of GHIs and some alignment initiatives, 2000–2023. Source: Witter et al. 2023[7]. Image credit: Claudia Molina

Global KIs perceived competition for funding between GHIs and other global-level organisations, creating a sense of a zero-sum game, where funds may also not align with the actual needs in terms of disease burden or the functional role of different organisations. The competition for funding from the same pot of money was perceived to be likely to contribute to a perceived eagerness of GHIs to take on new roles and expand their mandate, as organisations jostle for roles and funding. The existing system of staggered replenishments by GHIs was perceived as challenging for bilateral donors and governments of LMICs to manage [50,51,52] and there were concerns regarding the overall financial sustainability of the repeated, increasing GHI requests for replenishment.

At country level, dependence on GHI resources can lead to imbalances in relation to priority areas and loss of alignment. In Senegal, for example, despite low prevalence, HIV programmes continue to receive substantial funding, whereas non-communicable diseases, which are more prevalent, lack sufficient resources (KII and [46]). This was echoed in the South African case study, where despite the high HIV prevalence concerns were raised that not enough finances were being directed to non-communicable diseases and strengthening of primary health care.

At the country level, some GHIs wield considerable power, depending on their contribution to the country’s domestic funding. GFATM and Gavi are important funders to governments, NGOs and civil society. A comparison of WHO’s Global Health Expenditure Database (April 2023 update) [53]and OECD Creditor Reporting System [54] data indicates that Gavi and GFATM gross disbursements accounted for a larger combined budget than domestic government funding in seven sub-Saharan African countriesFootnote 1 in 2020, giving these two institutions considerable influence. As an interesting contrast, in South Africa DAH constitutes less than 5% of total health expenditure, with the GFTAM providing the largest share of funding for HIV and to a lesser degree TB and malaria.[53] KIs reported that this small contribution to the overall budget does limit their power at governmental level. As in other countries, GFATM and Gavi also work through a variety of channels and by empowering non-state actors or disease-specific programmes they are still capable of creating advocates for them. Lack of transparency can also cause challenges for managers at devolved levels:

“In Ghana, in talking to district managers, they were so frustrated because these donors were coming in, running their funding off budget and basically bypassing them… The district managers have very little power in how these resources are allocated, but they’re held accountable for delivering within their districts. It’s crazy, right? And there’s so much frustration at that level. I think from a governance side they should be very transparent.” (Global KI).

There are also imbalances within government, as funds go disproportionately to some programmes (such as HIV/AIDS and malaria), which creates inequities and also vested interests amongst some Ministry departments. For instance, in Mozambique, a KI reported that 80% of the funding received is for HIV, which creates a set of vested interests out of balance with the rest of the health system, and little incentive for these recipients to support a more integrated system. The ability to gain such disproportionate benefits from GHI funding, including as a result of the opaque mapping of funding to public expenditure, creates pockets of strong resistance to reforming the GHIs as they are currently functioning at country level.

By contrast, GFF works through more an integrated funding mechanism, which raise different concerns about fungibility.

“Financing takes the form of budgetary support or trust funds, producing a substitution effect between donors and governments. How can we explain the fact that, while budget support increases, health expenditures and needs remain unmet?” (SEARO consultation KI).

Moreover, provision of funding is perceived as not tied to a country plan led and owned by Ministers of Health and instead is tied to programmatic funding cycles of Gavi and GFATM, with an imperative to disburse funds rather than support national planning. This results in the provision of fragmented ad hoc funding and exacerbates frustration within country governments, which feel disempowered to direct resources or ensure accountability:

“The power lies with GHIs so far. They send you the support but you do not have a say. If you do not have a say, you do not have power” (Pakistan KI; see also Tables 4, 5 and 6).

Some countries have shown notable progress in adopting a more integrated approach – for example, Malawi is currently making progress on greater integration [55]; additionally, Ethiopia, Rwanda, Somalia, and certain provinces of South Africa have been recognised as enforcing a more harmonised approach across funders, including GHIs [56]. There is scope for countries to shape GHI support, where will and capacity exist, but this is not always facilitated by the GHI requirements.

According to South African KIs, GHIs and larger donors often by-pass government, due to lack of trust, instead providing direct funding to NGOs, CSOs, Parliament and higher education and research institutions, undermining control and overview of central institutions such as the Department of Health and Treasury. Reportedly, approximately half of the GFATM funds are allocated to government recipients, but even among those, a significant portion remains off-budget [54, 57]. In pursuit of their goal to channel 55% of funding through government systems by the end of 2021, Gavi has made strides in increasing the share. However, as of 2021, only 41% of the (non-commodity) funding had been directed through these systems.

Country KIs are also sceptical about the small proportion of funding that is expended within countries. Only operational funds of country grants are actually spent in the country whereas the bulk of the funding often comprises supplies which are internationally procured as local vendors are not pre-qualified for GHI procurement. There have been long-standing concerns of lack of international community support to boost the local industry for supplies production, which leads to a cycle of dependency on GHI funding.

“Local vendors are not pre-qualified, so we end up sending back 70% of the funding to donors through international procurement and that at a much higher cost compared to the local purchase”. – (Pakistan KI).

Despite the focus on minimising fiduciary risks, there are also concerns that the GHIs (GFATM and Gavi in particular) may inadvertently contribute to or escalate corruption risks. This concern stems from the use of multiple independent bank accounts and off-budget systems, which can create opportunities for financial irregularities. Periodic crises have been linked to poor accounting practices and inadequate tracking of fund usage [58,59,60,61,62].

Narratives and framing

Performance narratives

GHIs justify their existence based on results achieved in their focal areas, but there is considerable contestation about how those results are generated and whether they reflect others’ investments along the results chain. While the GHIs are recognised to have made substantial contributions to the results chain for their focal areas, many global KIs and the literature [17, 63, 64] reported that some of them over-claim results, especially on blunt indicators such as ‘lives saved’. Specifically, they are perceived to claim credit for the entire outcome of broader investments, which encompassed contributions from LMIC governments and from other funders. In some cases, reported results have been primarily based on modelling, rather than comprehensive evaluations.

“They collect the receipts for inputs, but they don’t really know what those inputs are producing.” (Global KI).

The GFF has moved away from this model and reports on assessed contribution to national/country results, with a clear line of sight to the nature and value add of the GFF contributions, which made their reported results less questioned by KIs. However, this was mentioned by some KIs as having weakened their case for impact in comparison to some other GHI claims. This shows the pressure that GHIs are under to compete and ‘out claim’ one another in order to attract or maintain funding.

In response to concerns about health system impacts [65, 66], there has been an increased focus in GHI policies on ‘HSS’ investments. However, with GFATM the classification of spending as supporting resilient and sustainable systems for health (RSSH) was also questioned by global KIs, who claim that what is counted as RSSH and what is seen as disease-specific does not follow a clear logic. There has been ongoing debate and lack of clarity around how much money spent by GFATM and Gavi can be classified as actually strengthening the health system in a sustainable way [67]. Various attempts to classify expenditure have been made, ranging from 27 to 7% of investment [68, 69].

Several KIs mentioned that the narrative is dominated by what they interpreted as powerful and vocal interests grouped around the GHIs at global level, which have strong interests in emphasising the strengths and successes of GHI activities, and have the resources to amplify this message. This is in contrast to more critical voices at country level and globally, which are not able to project their views with such power. As was highlighted in the governance section, some Board members also feel less able to speak out in the face of these power differentials.

Narratives about capacity

At the national level, particularly in contexts of financial dependence, there can be a mutual blame game, in which GHIs and other partners lament lack of national capacity and planning which forces them to play a dominant role, while national counterparts resent their lack of control, ownership and independence, blaming GHIs for undermining these and not building their capacity. Both sides have an element of justice and the behaviour on both sides can reinforce continued patterns of this nature.

‘The government is meant to set targets but, in reality, GHIs set priorities because the government lacks the capacity to do so. The country is thus pushed to achieve targets set elsewhere with little regard to the local context (e.g. economic climate, available resources, burden of disease, political realities). This is because of very limited state capacities, reflected in a weak national programme, a Health Department with no clear vision or capacity, and the absence of a public health approach, a realistic health financing strategy, or medium-term (five-year) and long-term (15–20 year) plans.” (Pakistan KI).

Part of the challenge relates to the timeframe and institutional incentives of GHIs, which have relatively short funding cycles, while building capacity takes longer and is more complex to measure.

“[GHIs are] top-down, selective, short-termist, and biased towards delivering results that can be measured, In a neglect of important things that need to be improved or strengthened, but which can’t be captured in ways these initiatives prefer to measure things – which is by counting.” (Global KI).

“Health systems work is by nature difficult. Part of what it achieves is preventing more bad things from happening. That’s always difficult to gauge and assess” (Global KI).

Some of the divergence of discourse on the impact of GHIs relates to respondents focusing on different outcomes – in particular, short-term gains in coverage in specific areas versus longer term changes to how system operate. The fact that GHIs primarily fund inputs means that there is continuing dependence in the longer term.

“We’ve done really well over 20 years in bringing down the incidence rate of HIV, saving people from dying of HIV with TB and malaria as well. But of course as soon as the money dries up, that all starts to disappear, all those gains, and that’s what we saw over COVID, right?” (Global KI).

Narratives about risks

It is also important to understand how risks are framed. The GHI systems are in many cases primarily designed to prioritise minimising fiduciary risk, which is crucial for donors. However, that may not be inherently more important than addressing programme and system risks, such as failing to achieve progress, strengthen programmes, or causing unintended harm to health systems. Enhancing effectiveness may involve increasing flexibility, even if it results in higher fiduciary risk. This aspect becomes particularly significant in fragile and conflict-affected settings, where the circumstances are dynamic and require adaptability. KIs point out that more work needs to be done on balancing the costs of different approaches and using more context-adapted measures.

“There is a problem with the financing flexibility. The Global Fund, for example, has very strict budget lines and in conflict settings, it does not allow us to adapt according to the current situation.” (EMRO consultation KI).

Narratives about potential reforms

The analysis of the interview data revealed divergent perspectives on the role and possible future path of the GHIs (summarised in Table 7). Some implementers and funders were incrementalist in their approach to change, whereas other country-level actors, multilaterals, and academics tended to be more radical. There is also a lot of variation within these groups. It is notable that there were surprisingly critical voices from within the GHIs themselves, reflecting the divergent pressures that staff within them are having to manage.

The positive narrative about results noted above makes changes to the status quo more difficult. GHIs rely heavily on these narratives to make the case for their continued importance and existence, providing information systems and data to support their positions. At the same time, critical narratives emerged from our interviews, which support radical reforms. There is a discrepancy between these more radical voices and the official narratives within GHIs about reform, which weakens the possibility of agreement on the way forward.

While reforming existing institutions is challenging, establishing new institutions appears to be an altogether easier route to plan to respond to new global challenges. Hence proliferation and fragmentation are perpetuated, impacting on recipient countries. Over the past few years, several new global funds have been created, including the Global Oxygen Alliance [70], the Hepatitis Fund [71], Health4Life Fund [72], the Pandemic Fund [73], and the Health Impact Investment Platform [74]. The relevance, functioning and unintended consequences of these new funds, largely supported by the same bilateral donors, UN agencies and foundations, need to be evaluated. They add a new layer of complexity and fragmentation to the global health architecture and at national level, where each initiative focuses on a specific field, such as sexual and reproductive health and rights, HIV, or innovation, and operates with its own programs, governance structures, mechanisms, and approaches.

“The mechanisms are fragmented, but the public health problems they tackle are not” (Senegal KI).

Another potential reform that was mentioned is the expansion of mandates of existing GHIs. However, some interviewees, especially global KIs, expressed concern about what they perceived as constantly expanding mandates, particularly regarding the GFATM and Gavi. They pointed out that these organisations have been expanding their roles and venturing into new areas, such as HSS [65, 69]. However, in their opinion, there is little evidence to suggest that GHIs are appropriately structured and technically equipped to handle these responsibilities effectively (South Africa KI; regional consultation).