The real Man of Steel wasn’t woke, but he was radical.

The American right has launched another of its characteristically soul-crushing and stupefying culture wars, this time targeting Superman. James Gunn, the director of the latest iteration of the franchise, simply titled Superman, provided the casus belli by innocently telling The Times of London, “Superman is the story of America. An immigrant that came from other places and populated the country. But for me it is mostly a story that says basic human kindness is a value and is something we have lost.” While these mild words might be read as a subtle rebuke to Donald Trump’s xenophobia, they hardly amount to a ringing promise to use the Superman character to challenge the status quo.

To Fox News, though, Gunn’s anodyne comments were proof that Superman was about to become “Superwoke.” The network’s host made a strange joke that the superhero’s cape will now read MS-13. Former Donald Trump adviser Kellyanne Conway told Fox, “We don’t go to the movie theater to be lectured to and to have somebody throw their ideology onto us” and doubted if a liberal Superman movie would be a success. This prediction that a Superwoke movie would bomb was widely echoed on the right.

It turns out Conway and crew are flops when it comes to box office prognostication. Gunn’s Superman is in fact a smash hit, so far raking in more than $425 million. Despite the right’s claim that the movie is anti-American, it actually did much better in the United States than in the international market (a situation that Gunn, ironically, blames on Trump’s global unpopularity, which is hurting American cultural products).

The most sophisticated critique of the movie from the right came from Daniel McCarthy, the editor of the intelligent traditionalist journal Modern Age. Writing in his magazine, McCarthy accurately noted that “Superman is a product of the New Deal. His creators, Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel, were Jewish teenagers from immigrant families (Shuster was a Canadian immigrant himself) who became friends and creative partners in Cleveland, Ohio.” McCarthy contrasts the robust liberalism of the New Deal, fully assured of its power and America’s ability to save the world, with the more anemic contemporary liberalism reflected in Gunn’s movie. In the new iteration of Superman, the Man of Steel is often beaten up—and is just one superhero in a universe of other fantastical beings. To McCarthy, this fault—along with what he sees as a reluctance to affirm the goodness of Kansas culture—is symptomatic of a rootless, post-national liberalism.

McCarthy’s criticism doesn’t quite work. Superman has always been strong, but never completely invulnerable (at the very least, he can be brought down by kryptonite). For obvious narrative reasons, stories about an all-powerful being who cannot suffer would be boring, so there have been many stories about Superman’s vulnerability long before the current movie. And contra McCarthy, the film goes out of its way to affirm that Superman’s adoptive parents, old-fashioned farmers in Kansas, are crucial to his learning to be human.

The value of McCarthy’s essay is that it reminds us of a fact too often ignored by contemporary critics, especially right-wing ones: the New Deal origins of the character. Shuster and Siegel first came up with the idea of Superman in 1933, in the very depth of the Great Depression. The early story was a dystopian science fiction about the dangers of science creating a superhuman being. This was of course an idea with much purchase given the rise of Nazism (Hitler coming to power that very year) and had been previously explored by many writers, most notably in Philip Wylie’s Gladiator (a 1930 novel that influenced Superman’s creators). Siegel and Shuster would play with the concept for a few years before finally selling it to Detective Comics (DC). The crucial decision they made in developing their protagonist was to turn the fearful racist idea of an Übermensch on its head by imagining a superman that adhered to democratic, egalitarian politics. (The word “superman” was not the only politically resonant phrase associated with the character. Beginning in 1939, he was known as the “Man of Steel” which—perhaps coincidentally—echoes another figure who had that moniker, Joseph Stalin).

In effect, Superman was based on the idea that America could respond to the fascist Übermensch with its own compassionate and justice-seeking Superman. Another layer of allegory was provided by the hero’s dual identity. Just as the United States had been weakened by the Depression but stood ready to remake itself as a global savior, so the new hero was both the meek and mild Clark Kent—and, in reality, a larger-than-life dynamo. Of course for those who grew up in a Jewish immigrant milieu, as Siegel and Shuster did—or indeed any immigrant milieu—the theme of dual identity had a personal resonance as well.

The earliest Superman comics done by Siegel and Shuster reflected not just the New Deal but the broader radical politics of the Popular Front. Superman in these stories was not concerned with affirming the justness of the status quo but rather with challenging those powerful forces, including business interests, that oppress the people.

Superman premiered in Action Comics #1 (June 1938). In the first story, Superman saves an innocent man who is about to be wrongly executed and then investigates the misdeeds of munitions manufactures who are bribing an American senator and stirring up a war in Central America. The arms dealer storyline is continued in Action Comics #2 (July 1938) and strongly echoes the finding of the Nye Committee, a Senate investigation into the arms industry (popularly called “the merchants of death”) that ran from 1934 to 1936. In particular, the fictional war that Superman stops in the story parallels the Chaco War (1932–35) between Bolivia and Paraguay. The Nye Committee found that the merchants of death played a sinister role in egging on both sides of that war. Superman’s arch foe, Lex Luthor, is in his first appearance in 1940 shown to be a war profiteer.

In Action Comics #3 (August 1938), Superman tackles capitalist exploitation in the mining industry. The story opens with Superman rescuing a group of miners trapped in a cave-in. In his guise of the reporter Clark Kent, Superman interviews a miner named Stanislaw Kober who has been crippled by the accident. Kober tells Superman/Kent, “Months ago we know mine is unsafe—but when we tell boss’s foremen they say, ‘no like job, Stanlislaw? Quit!’”

Superman/Kent then goes to interview the mine owner, Thornton Blakely, who blames the accident on Kober’s “carelessness.” Scorning his workers, Blakely says he’ll offer to pay part of Kober’s medical bill and give him a pension of a $50 retirement bonus. Unsatisfied by this answer, Superman breaks into Blakely’s estate dressed as a miner. One of the security guards calls Superman a “bohunk”—a reference to the Central European origin of many mineworkers. Superman then engineers a situation where Blakely and his rich friends are themselves trapped in a mine and realize that faulty equipment could doom them. Of course, Superman saves them in the end, which leads Blakely to have a change of heart, promising to Clark Kent that he will now look after worker safety. Kent thinks to himself that if this promise isn’t kept, Blakely can “expect another visit from Superman!”

Writing in Cosmonaut magazine in 2023, Hank Kennedy listed other Superman stories where the superhero fought systemic injustice:

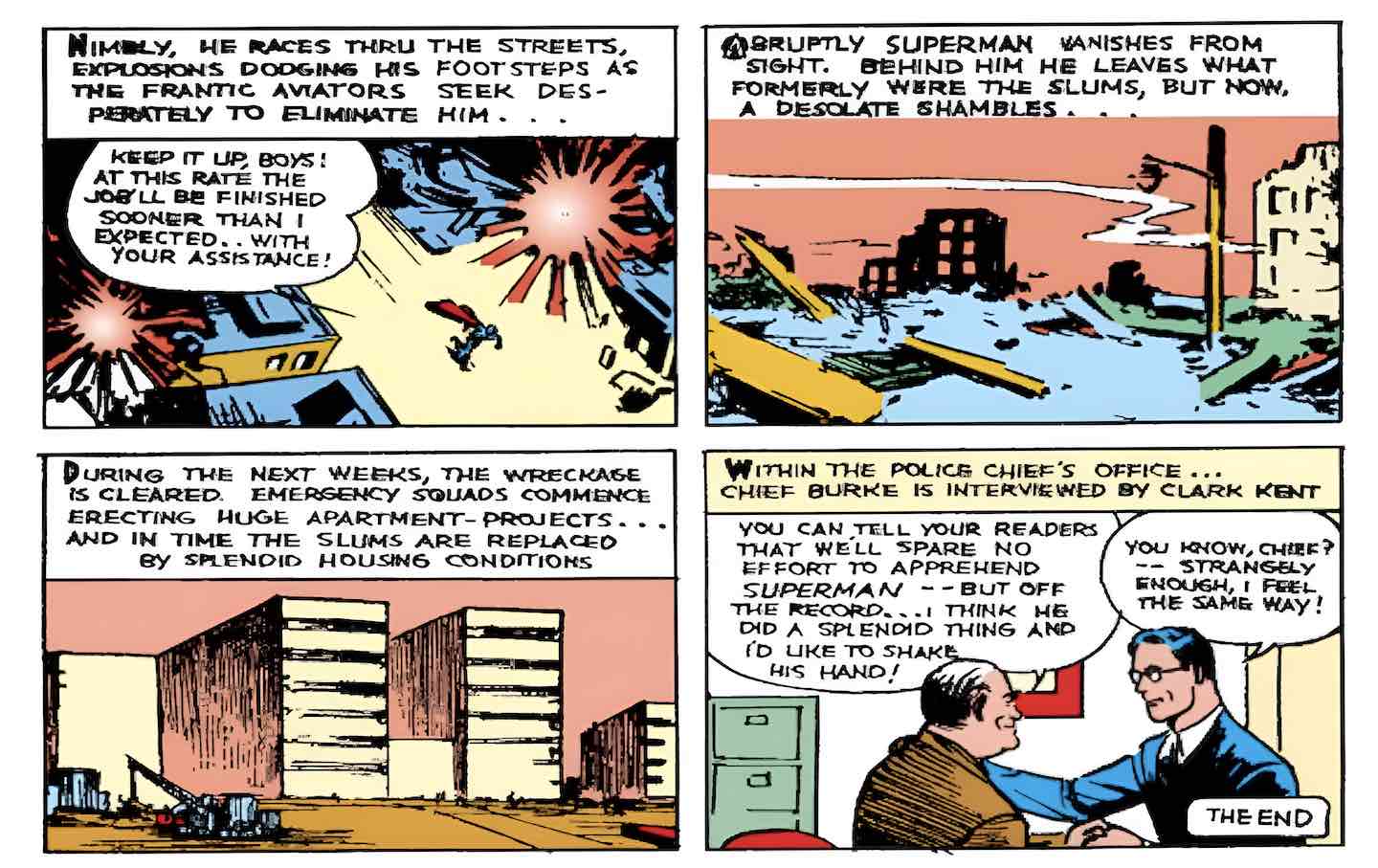

Superman destroys slum housing in Action Comics 8 (January 1939) to force the government to build public housing for the poor. Superman exposes the cruel mistreatment of prisoners in Action Comics 10 (March 1939). In Action Comics 11 (April 1939) he goes after some stock brokers guilty of defrauding investors and in Action Comics 12 (May 1939) Superman addresses reckless driving and unsafe cars, anticipating Ralph Nader’s Unsafe at Any Speed.

As Kennedy notes, these radical themes started being phased out after World War II, when the character became more of a nationalist Boy Scout defending the status quo. This reflected a broader rise of conservatism after the New Deal era ended. By this point, the original creators Siegel and Shuster, victims of a notoriously unfair contract, had lost any creative control and the character had fully become a corporate intellectual property controlled by DC Comics.

The radical and left-liberal politics of the original Superman were shared by many other pioneers in the comic book industry. Like Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, many of the early cartoonists were the children of immigrants or immigrants themselves, often from Southern and Eastern Europe. Perhaps the most creative figure in comics was Jack Kirby (born Jacob Kurtzberg) who cocreated Captain America, the Fantastic Four, the Hulk, Black Panther, and many other characters. Kirby was a lifelong left-liberal, described by his son as having Bernie Sanders politics. The publisher Lev Gleason, who published best-selling titles such as Daredevil and Crime Does Not Pay in the 1940s, was a member of the Communist Party and often worked social justice themes into his comics. The rowdy plebeian spirit of the early comics provoked a backlash in the early 1950s, leading to a Senate investigation and the industry’s adopting a strict code of self-censorship.

Distant echoes of Superman’s early radicalism can be heard in James Gunn’s new movie, but only in muted form. As Daniel McCarthy notes, “Gunn’s movie is not very political by today’s standards.” Superman does stop a powerful American ally from attacking a neighboring state, a scenario that has enraged some Zionists who see it as a critique of Israel’s onslaught in Gaza. This allegorical interpretation is likely accurate, although taking offense at it says more about the bad conscience of pro-Israel nationalists than it does about the politics of the film.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

In the movie, Lex Luthor clearly invokes tech bros such as Elon Musk and Peter Thiel: Luthor uses his alignment with Washington to push for a surveillance state and extrajudicial internment camps. Again, this is an allegory that progressives should welcome, but it is overlaid with so much science fiction gimmickry that it loses its force. Gunn’s Superman is not so much woke as convoluted and allegorically indirect.

The original 1930s Superman, created by two desperate teenagers living in country knocked flat by an economic depression, had a directness that the current incarnation lacks. The comics were rudimentary and primordial, speaking to an elementary sense of justice. They emerged into a world where class conflict was sharper and more visible than in later decades. When the original Superman met an arms dealer or an abusive mine owner, he went at them with his fists. The current Superman is more uncertain about who his enemy is: He is more of a Barack Obama liberal than a 1930s Popular Front superhero. But, who knows, if the world keeps getting worse, the spirit of the original radical Superman might yet return.

More from

Jeet Heer

The Democratic National Committee’s forthcoming “autopsy” is a cover-up to protect the failed leaders who twice lost to Trump.

Jeet Heer

Partisan politics is making a travesty of justice.

Jeet Heer

From the Cold War till Donald Trump, there’s always been a special dispensation for hawkish bigots.

Jeet Heer

The Epstein scandal deserves a real investigation, not Trump’s hand-waving cover up.

Jeet Heer

Trump’s defense secretary loves taking selfies while presiding over administrative anarchy.

Jeet Heer

By attacking equality of citizenship, MAGA is smashing the foundations of national pride.

Jeet Heer