This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with the North Dakota Monitor. Sign up for Dispatches to get our stories in your inbox every week.

Reporting Highlights

- Seeking Help: North Dakota mineral owners asked state leaders to help them get information from oil companies.

- Oversight Program: Lawmakers created a royalty oversight program. It had support from the industry but was less than mineral owners wanted.

- Limited Scope: The program has solved some concerns, but it has failed to address a major one.

These highlights were written by the reporters and editors who worked on this story.

One morning in February 2023, a small group of mineral owners arrived at the North Dakota Capitol on a mission. They had traveled from across the state and other parts of the country to explain to lawmakers how the powerful oil and gas companies had been chipping away at their income.

It’s not easy to recruit people to testify during the winter months of the legislative session. Ranchers are busy with the calving season. Snowbirds have relocated to warmer climates. It’s a more than three-hour drive for those living in the Bakken oil field.

But those who made it to Bismarck lined up at a podium to share details of their own experiences and the broader concerns affecting the estimated 300,000 people who receive money from the industry in exchange for the right to their underground minerals. For nearly a decade, they had grappled with companies withholding significant portions of their royalty payments without explaining how they determined how much to deduct, as the North Dakota Monitor and ProPublica reported last week.

Now they were at the Capitol for a specific reason: They wanted legislators to require companies to provide more information so owners could discern if they were being paid correctly, and to impose penalties if companies failed to comply.

Shane Leverenz, who manages income his extended family receives from numerous oil wells, read aloud email responses from companies to illustrate the lack of cooperation mineral owners face when they request information. “We are not obligated to mail each owner a calculation as to how their interest was calculated,” one company wrote.

“There is no transparency,” Leverenz told the legislators. Leverenz, whose great-grandfather homesteaded in North Dakota and had his property deed signed by President Theodore Roosevelt, has helped organize royalty owners on this issue in recent years. Leverenz grew up in Epping, a town of fewer than 100 people in the northwest part of the state, and traveled to North Dakota from Texas, where he now lives, to testify.

Credit:

Jeremy Turley/Forum News Service

After input from Leverenz and others, lawmakers decided to create a new state program that they hoped would address conflicts between royalty owners and companies. In particular, mineral owners had mounting concerns over postproduction deductions, the money companies withhold to cover the costs of processing and transporting minerals after they are extracted and before they are sold. Companies say they are allowed to pass on a share of those costs, while royalty owners say they shouldn’t bear that responsibility because in most cases lease agreements don’t mention those expenses.

The state’s “postproduction royalty oversight program” had the support of the industry, but it was far less than what Leverenz and other owners wanted. In the two years since its creation, the program has not lived up to its name and has not alleviated owners’ concerns over deductions or transparency, an investigation by the North Dakota Monitor and ProPublica found. The program has resolved 69 cases so far, and none have involved postproduction deductions, according to documents obtained under a public records request. A case can represent a complaint or question from a royalty owner.

“The legislative intent was supposed to be addressing the issue of the postproduction costs that they were hitting people with,” said Rep. Don Longmuir, a Republican from Stanley, in the northwest corner of the state.

The newsrooms’ investigation found that the program has focused on other issues. It has instead helped owners resolve complaints about companies withholding payments entirely and failing to pay interest on late royalty payments, records show. Some mineral owners said in interviews that they do not trust state officials to help them get information about the deductions and therefore have not tried to use the program.

Leverenz said the program, also referred to as the ombudsman program, has not accomplished what he and other royalty owners were told it would. He has taken six complaints to the ombudsman; three were resolved but three remain open, including two for more than a year. The unresolved complaints do not involve deductions, he said, and focus on other issues with his family’s royalty payments.

“The ombudsman is running into the same thing that I have, where there’s just no response from the oil companies or they stalled,” Leverenz said. “There’s been no forward momentum.”

Ron Webb, who coordinates the program within the state’s Department of Agriculture, said it has helped facilitate communication between mineral owners and companies. He said the program is voluntary and does not have authority to compel companies to change how they calculate payments or even to provide information. “Oil companies are not required to work with us,” Webb said.

The program no longer promotes itself as being able to oversee concerns about royalty deductions even though that was part of the legislative intent. On the department’s website and in a brochure, the word “postproduction” has been dropped from the program’s name even though it is in the title of the law that created it.

The department’s legal counsel, Dutch Bialke, said the name of the law is irrelevant to how the program operates.

“The title is entirely legally non-binding and has no legal effect,” he wrote in an email, citing North Dakota law.

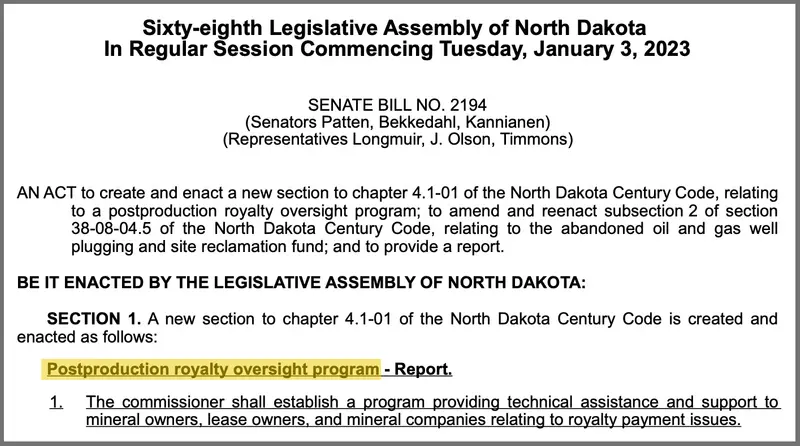

Credit:

Obtained by North Dakota Monitor and ProPublica. Highlighted by ProPublica.

“Nothing Is Clear”

Ever since Neil Christensen and his sisters noticed in 2016 that Hess Corp. was withholding nearly 25% of their royalty income — up from less than 1% just two years earlier — his family has tried to get answers from the company.

He traveled to Minot, North Dakota, some years ago to meet with Hess representatives at their production offices. He also called the company’s accounting office and its royalty owner hotline, but he said their explanations didn’t make sense.

“It doesn’t seem as if the company has a large interest in explaining themselves,” Christensen said. Spreadsheets kept by his family show withholdings have been as much as 42% in recent years. “The transparency issue is a big problem with oil operators and mineral owners.”

The royalty statements can be hundreds of pages long but provide only a general description of the reasons for the deductions, leaving owners unable to verify the companies’ costs and whether they are being paid a fair share. Christensen’s family and others said they have had payments reduced for expenses the companies incurred years earlier.

“Nothing is clear,” said his sister Naomi Staruch, who has spent most of her career working in finance for banks and churches in Minnesota. “I would get so frustrated really looking hard at the statements.”

Diana and Bob Skarphol, who have advocated for years on behalf of royalty owners, said confusing and overwhelming royalty statements are a common concern. The couple received one statement last year that included 39 pages of calculations for a single well — including reductions to past royalties going back nine years. The Skarphols received $1.15 that month from the production of the well.

Merrill Piepkorn, a Democratic former state senator from Fargo who was the prime sponsor of the transparency legislation, said oil companies’ tactics are “obfuscation through transparency.”

“You get so much information, there’s no way to find what you’re looking for,” said Piepkorn, who unsuccessfully ran for governor in 2024.

Todd Slawson, chair of the North Dakota Petroleum Council, said royalty statements are complex in part because state regulators within the last decade began requiring companies to include additional categories of information. Hess said it maintains an online portal where royalty owners can access their royalty information and operates a call center that mineral owners can contact with questions.

North Dakota does not regulate the costs that companies can pass on to individual owners, though the state and federal governments regulate deductions on government-owned land. The state audits the royalties paid on state-owned minerals to ensure the amounts are correct and, since 1979, the state’s leases do not allow deductions. But private mineral owners don’t have that same access and often learn about deductions by comparing their statements with one another.

“It’s kind of all rigged against the individual royalty owner,” Leverenz said.

State officials have told mineral owners that they can’t get involved in private disputes and that litigation is the owners’ best recourse. But litigation isn’t financially feasible for most families, according to attorney Josh Swanson, who represents mineral owners.

“It easily exceeds six figures, and that’s cost-prohibitive for most folks,” Swanson said. “Part of the playbook for a lot of operators is making these things as cost-prohibitive as they can.”

Swanson was the attorney Janice Arnson and her family hired to try to get answers from Hess. Hess had been deducting between 15% and 36% of their royalty income each month since 2015, according to a spreadsheet maintained by Arnson. They had no luck getting an explanation from the company until they hired Swanson in 2017. When Hess responded, a company attorney said in a letter that the deductions were “proper and permissible” under the terms of the lease. While Swanson disagreed, the family declined to pursue litigation because “it was going to be an expensive suit.”

“We were one small, little family,” said Arnson. “We just didn’t have the resources against Hess to fight.”

(Hess did not contest or comment on Arnson’s or Christensen’s claims.)

Some royalty owners have turned to the Northwest Landowners Association, a nonprofit advocacy group, for help. Troy Coons, the group’s chair, said he has fielded multiple calls a week from royalty owners who are angry that state leaders have not helped them with the deductions. “It’s a massive concern for people,” said Coons, whose group has sued the state on behalf of property owners on a different issue. “We’re not supposed to be bearing the burden of expenses.”

Lawmakers initially had bipartisan support in 2023 for a bill that would have guaranteed mineral owners access to electronic spreadsheets detailing their payments and would have required companies to provide more information on how they calculate a royalty owner’s share of the income from each well. It also would have directed courts to require companies to reimburse royalty owners for attorneys’ fees if they successfully sued for the information.

But that bill was discarded in favor of legislation creating the royalty oversight program.

The Legislature “took our bill and they stripped it of everything, and they shoved the ombudsman program into it,” Leverenz said. They created the program “with the promises that, you know, this is going to be the answer to all the issues that have been brought up over the years with the royalty owners.”

Sen. Brad Bekkedahl, a Republican from Williston, initially backed both bills. The senator said he hoped the bill creating the ombudsman program would be amended in the legislative process to give it more authority to advocate on behalf of mineral owners. That didn’t happen.

“That would have been, I think, more beneficial to royalty owners,” said Bekkedahl, who ultimately voted against it.

“Barking Up a Tree”

In pitching the program to lawmakers in 2023, Doug Goehring, the state’s agriculture commissioner, said the goal was to “try to develop some resolution” for royalty owners with questions about their payments, including concerns over deductions.

The bill required a report to legislators. Goehring told lawmakers he would share with them “full and complete information concerning the cases” handled by the program and the issues faced by mineral owners in order to inform future legislation. “We’ll certainly provide you scenarios, situations, and some of the challenges and difficulties we’ve dealt with,” Goehring, a Republican, testified in 2023. “And even some suggestions about how you correct some of this moving forward.”

The result has fallen short of what Goehring pledged in testimony, the news organizations found. Goehring now says it is not the program’s job to find resolution for royalty owners who question the deductions. “We don’t have a leg to stand on to try and advocate or try to extort money out of the company,” Goehring said. He said an exception is if deductions are specifically prohibited in leases, but most agreements, especially those signed decades ago, are silent on the issue of deductions.

Instead of a detailed report, Goehring delivered a one-page summary to legislators in September that broadly categorized the issues handled through the program. Legislators accepted the report without discussion. Goehring said a more detailed report was not necessary. “They don’t want to know that,” he said. “We generally don’t write reports in that manner. We give them the basic information.”

Credit:

Kyle Martin for the North Dakota Monitor

Of the 147 cases filed with the program, about half remain unresolved, including more than two dozen that have been pending since 2023. Goehring said some of the cases remain open at the request of royalty owners.

Two of the pending cases involve postproduction deductions, including one that has been open since September 2023, according to Bialke, the Agriculture Department’s legal counsel.

The cases are assigned to two energy companies that serve as ombudsmen, Diamond Resources and Aurora Energy Solutions, which contact the companies on behalf of the mineral owners. Neither of the companies responded to questions from the North Dakota Monitor and ProPublica.

The news organizations paid $425 to obtain records related to the cases that had been resolved as of late June. In those cases, the ombudsmen have answered royalty owners’ questions and obtained answers for them when companies had not been responsive. In some cases, they mediated solutions that resulted in royalty owners receiving payments they were owed, records show.

In one case, an ombudsman spent nearly 10 months going back and forth with a company until the royalty owner got paid. In other cases, ombudsmen helped royalty owners understand technical issues related to taxes and the probate process after inheriting minerals. The department redacted company names from the documents released, with Bialke citing state law.

“It has been extremely helpful for frustrated royalty owners who cannot get their questions answered,” said Slawson of the North Dakota Petroleum Council, who also owns an energy company. “Having deductions suddenly show up on revenue checks and questions not being answered or not explained well can lead to suspicions of wrongdoing.”

Kenneth Schmidt, who owns minerals near Ray in Williams County, contacted the program after struggling to convince a company that it owed interest on late royalty payments as mandated by state law. It took a few months, he said, but the company paid him.

“I was very satisfied with the program,” said Schmidt. “Instead of going to an attorney and I’ll pay $400 an hour, they did it for free, but through the state.”

Goehring said the program has been successful, citing feedback from the industry as well as the fact that no bills related to royalty deductions were introduced during this year’s legislative session, the first time in nearly a decade.

“If there’s no bills that are coming up, then isn’t that an indication? It’s kind of like if you don’t have a cough, then maybe you don’t have a cold,” he said.

While the program has resolved disputes like Schmidt’s, which are more cut-and-dried, it isn’t well equipped to handle more complex disagreements, Goehring said. That isn’t a surprise to one of the lawmakers who worked on the bill.

“I don’t doubt that in some cases, facilitating that communication probably helped, but I don’t think it gives all the answers to the royalty owners that they’re looking for,” Bekkedahl said.

A number of royalty owners told the news organizations they simply don’t trust the program to help. “I didn’t feel the ombudsman program had any teeth in it whatsoever to do anything,” said Brian Anderson, who has not filed a complaint even though he wants companies to more fully explain their deductions. “They’ll placate you; they’re not going to do anything about it.”

Curtis Trulson, a royalty owner in Mountrail County, agreed: Going to the program, he said, is just “barking up a tree.”