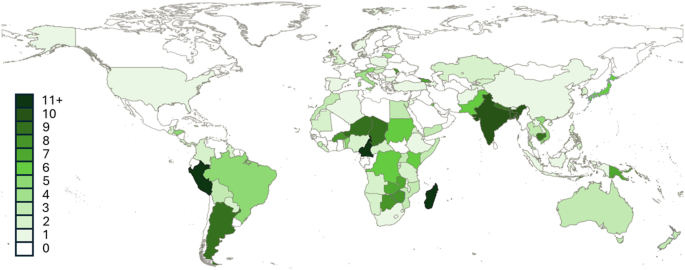

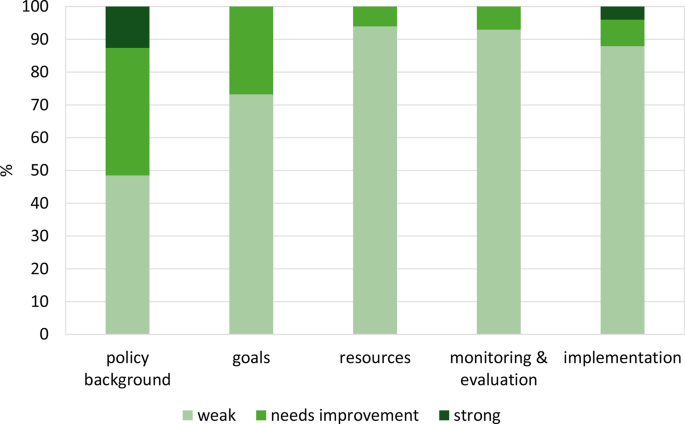

Climate-change policies worldwide had ineffective planning to safeguard child health, with 43% of countries obtaining a score of 0 (no mention of child health). Thirty-eight per cent of countries achieved a score of 1–3; these generally acknowledged the disproportionate health burden on children without providing any goals or actions. Low- and middle-income countries performed better than high-income countries, noticeably in South America, sub-Saharan Africa, and South Asia (Fig. 1). Policy backgrounds were the strongest areas overall (Fig. 2), but most policies fulfilled no criteria across all other policy determinants (Table 2). We provide a full list of policies evaluated and explanations for their scores in Supplementary Files 2 and 3.

Global distribution of climate-change policy scores for child health adaptation

Percentage of countries that fulfil none of the scored criteria (weak), some criteria (needs improvement) or all criteria (strong) across each policy determinant area

Policy background

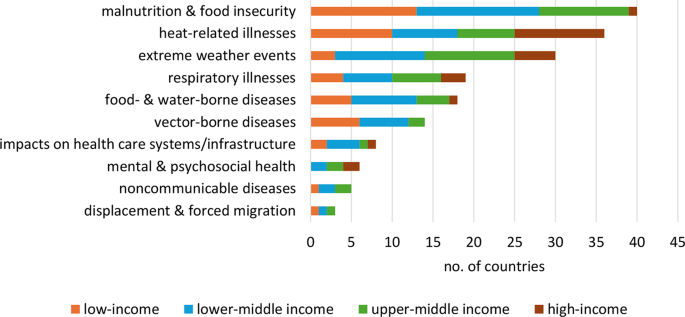

About half of the policies recognised that children were disproportionately affected by climate change, referring to them as a vulnerable group. The most common climate risks identified (Fig. 3) were malnutrition and food insecurity (n = 40), mainly recognised by low- and middle-income countries (Fig. 4), and heat-related illnesses (n = 36) which were often the primary focus of high-income countries.

Number of countries that identified specific climate-sensitive health risks for children in their policy backgrounds

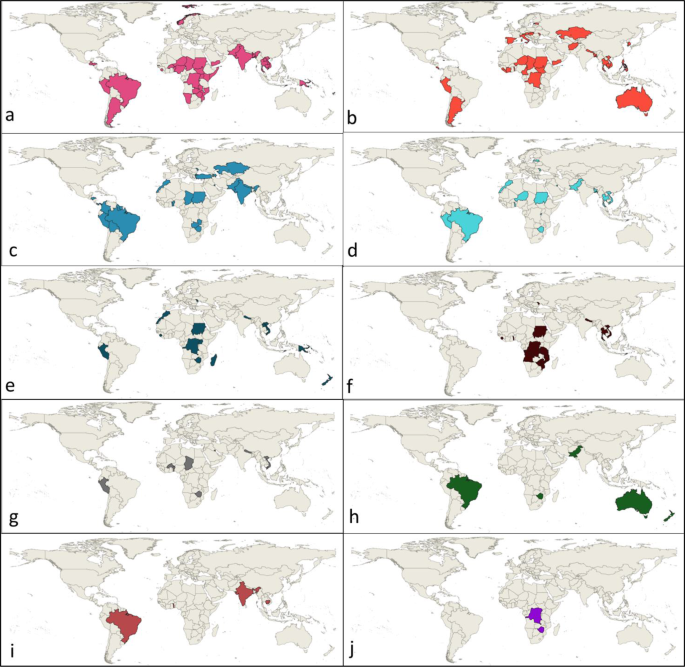

Global distribution of climate risks disproportionately affecting children identified in policy backgrounds. We categorised risks into (a) malnutrition and food insecurity, (b) heat, (c) extreme weather events, (d) respiratory illnesses, (e) food- and water-borne diseases, (f) vector-borne diseases, (g) impacts on health care systems and infrastructure, (h) mental and psychosocial health, (i) noncommunicable diseases, (j) displacement and forced migration

Where explicitly stated, the sources of policy backgrounds included multi-level stakeholder consultations, scientific articles, World Health Organization or United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) data, government publications, and vulnerability assessments.

Goals

Goals were rarely specific enough to be evaluated later for success. Only four countries described measurable child health outcomes, including malnutrition and diarrhoea (Sudan), childhood asthma (Virgin Islands), and general morbidity and mortality (India and Argentina).

Child health goals in low (n = 4), lower middle- (n = 5), and upper middle-income countries (n = 4) focused on improving health care, disaster-risk management, knowledge of health impacts, adaptive capacity, or physical and mental resilience, and reducing morbidity, mortality, violence against women and girls, or preventing harm. Goals rarely described specific climate-related health risks — where present, these included malnutrition, diarrhoeal disease, and extreme weather. High-income countries (n = 2) pledged to improve healthcare for vulnerable groups, including children, and to decrease general climate-related health impacts.

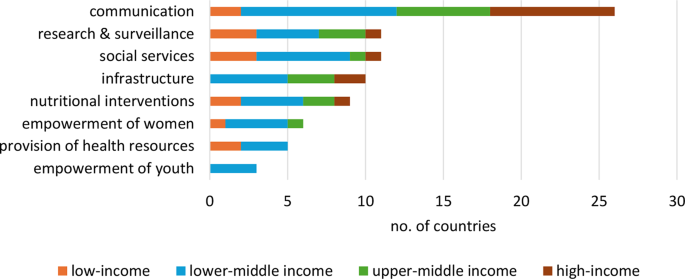

Forty-seven countries described actions that we categorised into (i) research and surveillance, (ii) provision of health resources, (iii) infrastructure, (iv) social services, (v) nutritional interventions, (vi) empowerment of youth, (vii) communication, and (viii) empowerment of women (Figs. 5 and 6). Actions could be categorised into multiple themes.

Number of countries that identified actions to protect child health

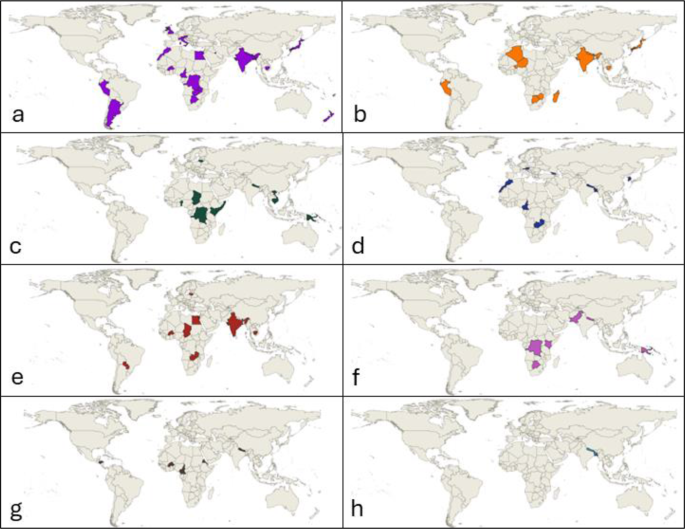

Global distribution of policy actions to improve child health categorised into (a) communication, (b) research and surveillance, (c) social services, (d) infrastructure, (e) nutritional interventions, (f) empowerment of women, (g) provision of health resources, (h) empowerment of youth

We provide summaries of each theme below.

i. Communication

Communication of climate-related health risks and adaptation behaviours was commonly described across all country income categories. In low- and middle-income countries, health information was communicated via social media campaigns, documentaries, exhibitions, libraries, brochures, television and radio shows, advocacy by community groups, school curricula, and demonstrations. Where the health information topics were specified, they mainly related to nutrition (dietary guidelines, nutritional deficiencies, and/or gastro-intestinal infections). Other topics included disaster preparedness and biomass smoke exposure within the home. The development of emergency response monitoring and communication systems for extreme weather events was also described. Information was targeted to women, school students, and primary healthcare personnel.

In high-income countries, communication strategies included school initiatives, websites, webinars, and integration of health information in the early education curriculum. Specific topics included extreme weather alerts (particularly for heatwaves), natural hazards, and disaster-risk management targeted to parents and school students. High-income countries rarely described actions outside of communication.

ii. Research and surveillance

Low- and lower middle-income countries described strengthening information-management systems for child health outcomes. Some outlined regular nutritional screening of children as well as pregnant and lactating women. Upper middle-income countries pledged to evaluate various health indicators ranging from vector-, food-, and water-borne diseases, extreme temperature exposure, food insecurity, impacts on medical infrastructure and the public health system, and healthy practices (unspecified). Japan was the only high-income country to address this theme, describing increasing scientific knowledge about the health effects of climate change on vulnerable populations (including children).

iii. Social services

Various social services and welfare programs were outlined in low- and lower middle-income countries. These included livelihood diversification, improved access to financial safety nets and insurance, free healthcare for mothers and children, and agribusiness enhancement to ensure food security and income generation. Lithuania was the only high-income country to describe social services that included subsidised tick-borne encephalitis vaccination for people under 18 years old, as well as free public transport for students (although this was not explicitly linked to child health).

iv. Infrastructure

No low-income countries outlined actions relating to infrastructure. Middle-income countries described the construction of climate-resilient emergency shelters and healthcare facilities, and retrofitting school buildings with insulation. Two high-income countries provided actions — Austria pledged to improve the climate-resilience of schools via shading solutions and drinking water fountains, and South Korea described retrofitting residential buildings with insulation.

v. Nutritional interventions

Interventions to improve food security were concentrated in low- and lower middle-income countries. These included the implementation or expansion of feeding programmes and guidelines, actions to diversify household diets, the expansion and promotion of fortified food consumption, and the enhancement of crop quality and harvesting techniques. Paraguay (upper middle income) described the construction of agroecological gardens in schools.

Lithuania was the only high-income country to include a nutritional intervention: the expansion and promotion of organic products at pre-school education establishments.

vi. Empowerment of women

Some policies linked improvements in child health to female empowerment, due to the disproportionate burden of childcare and household management faced by women. These were predominantly from low- and lower middle-income countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Cross-sectoral actions to reduce personal risk for women and girls in search of clean water were described, such as improving access to clean water and sanitation facilities and implementing local rainwater harvesting. Other actions included establishing a helpline for reporting gender-based violence and child marriage during and after disasters, training women in agricultural practices, providing access to enterprise funds, increasing income-generating opportunities, and generating gender-disaggregated indicators to improve emergency medical services. One upper middle-income country (Botswana) aimed to ensure the full participation of women and female-headed households in disaster management public gatherings. No high-income countries made commitments for empowering women.

vii. Provision of health resources

Provision of equipment, implements, and medicines was only in low- and lower middle-income countries. Specific resources included energy-saving cooking stoves in rural households and emergency kits. Burkina Faso was the only country to provide preventive malaria treatment for pregnant women and children. Cameroon intensified vaccine distribution programmes for a range of climate-affected diseases (diarrhoea, cholera, measles, typhoid, and others).

viii. Empowerment of youth

Three lower middle-income countries facilitated the participation of children and young people in disaster risk management initiatives — for example, by establishing youth-led volunteer groups for emergency response, rescue, and evacuation during disasters (Bangladesh). No other specific mechanisms were stated.

Resources

Only twelve countries stated the estimated or allocated financial resources for child-health actions, in the form of annual budgets or total estimated costs. No countries incentivised with rewards or imposed sanctions for spending the allocated resources on other programs. Human resources or organisational capacity was not addressed in any of the policies. Five low- and middle-income countries provided strategies to mobilise the allocated financial resources. Funding sources included government treasuries and international financing partners, such as the World Health Organization, United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), and other United Nations agencies.

Monitoring and evaluation

Measurable child-health indicators were rarely included; where present, these included preterm birth, malnutrition, respiratory disease incidence, and hypertension or other comorbidity rates in pregnant people. Timelines for data collection were similarly rare (n = 3), with follow-up occurring at one- or five-year intervals.

Implementation

Stakeholders involved in implementation included youth-led organisations, schoolteachers, various government departments, experts, senior policymakers, media companies, community organisations, and faith-based organisations. The responsibilities of individual implementers were rarely defined.