When President Trump campaigned for his second term on the promise of deporting millions of undocumented workers from the United States, farm groups were quick to voice their discontent. An immigration policy focused solely on removing those without legal status “would cripple agricultural production in America,” according to the American Farm Bureau Federation, a powerful agricultural lobbying group.

Economists, labor organizers, and immigrant rights advocates agreed. About 40 percent of farmworkers in the country are foreign-born, unauthorized workers, the U.S. Department of Agriculture recently found. Some farmers already complain that it’s hard enough to fill agricultural jobs domestically; without foreign labor, they argue, the nation’s food system would grind to a halt.

Now, the Trump administration appears to be making moves aimed at alleviating some of the economic burden felt by farm employers. Late last month, the Department of Agriculture announced the agency would end the survey used to set minimum wages for migrant farmworkers on temporary visas. Some farm groups welcome cheaper labor costs, but experts say falling wages — coupled with the administration’s mass deportation agenda — will ultimately scramble the business of hiring farmworkers.

The H-2A visa program allows farmers to hire seasonal workers from abroad, the vast majority of whom come from Mexico. These workers are paid according to something called the Adverse Effect Wage Rate, or AEWR. Every year, the AEWR is determined using the previous year’s Agricultural Labor Survey — more commonly referred to as the Farm Labor Survey, or FLS, which asks farm employers about their workers’ hours and wages. In a sense, the AEWR sets a wage floor for all farm laborers: U.S.-born workers must earn at least as much as H-2A workers when performing the same job.

In an announcement on August 28, the USDA said the agency would discontinue its use of the FLS, calling it “no longer necessary.” Without this mechanism in place, wages for farmworkers — regardless of their legal status — are likely to fall, experts say.

Some farm groups celebrated the move, arguing that AEWRs in recent years have grown too high and present a burden to their business. Daniel Costa, director of immigration law and policy research at the Economic Policy Institute, a non-profit think tank, argued that ending the FLS would usher in a new “wage rule employers have been begging for.”

But labor groups contend that farmworkers — whether they are guest workers, U.S.-born, or undocumented — are not paid a fair or even livable wage.

“What the Trump administration just did, it essentially liberalizes the entire labor market in the food system,” said Jose Oliva, campaigns director at the HEAL Food Alliance, a coalition of groups representing workers in the food supply chain. The resulting financial precarity would add another layer of risk to a profession that’s already one of the lowest paid in the country — as well as on the frontlines of the climate crisis.

Carlos Moreno / NurPhoto via Getty Images

Heat is the deadliest extreme weather event. For farmworkers, whose jobs include strenuous outdoor physical activity, that risk is even more pronounced. Researchers have found that workers in the agriculture industry are 35 times more likely to die from heat-related illness than any other workers. Beyond high temperatures, farmworkers are also especially vulnerable to other climate impacts — such as wildfire smoke and flash flooding.

“The job is already one of the more hazardous, dangerous, and deadly jobs, according to statistics,” said Costa, from the Economic Policy Institute. “It’ll probably get worse,” he added, noting that the Trump administration may or may not choose to implement a nation-wide heat safety standard for workers currently under review by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

The USDA did not respond to a request for comment.

“It is clear that the Trump administration is moving to cut wages for the H2A program,” Teresa Romero, president of United Farm Workers, a labor union, said in a statement to Grist. “Beyond the obviously harmful impact on H2A workers themselves, this will also undercut the wages of local farm workers, of all statuses including U.S. citizens.”

The H-2A visa program has grown steadily over the years, as farm employers have struggled to fill jobs with U.S. citizens. Some farmers call the program overly bureautic and burdensome — but many feel bringing in migrant workers is their only, or best, option when it comes to hiring, especially in an era where the federal government is set on deporting undocumented workers. Immigration raids on U.S. farms, part of the Trump administration’s mass deportation strategy will likely make farmers even more reliant on the migrant visa program, according to labor experts.

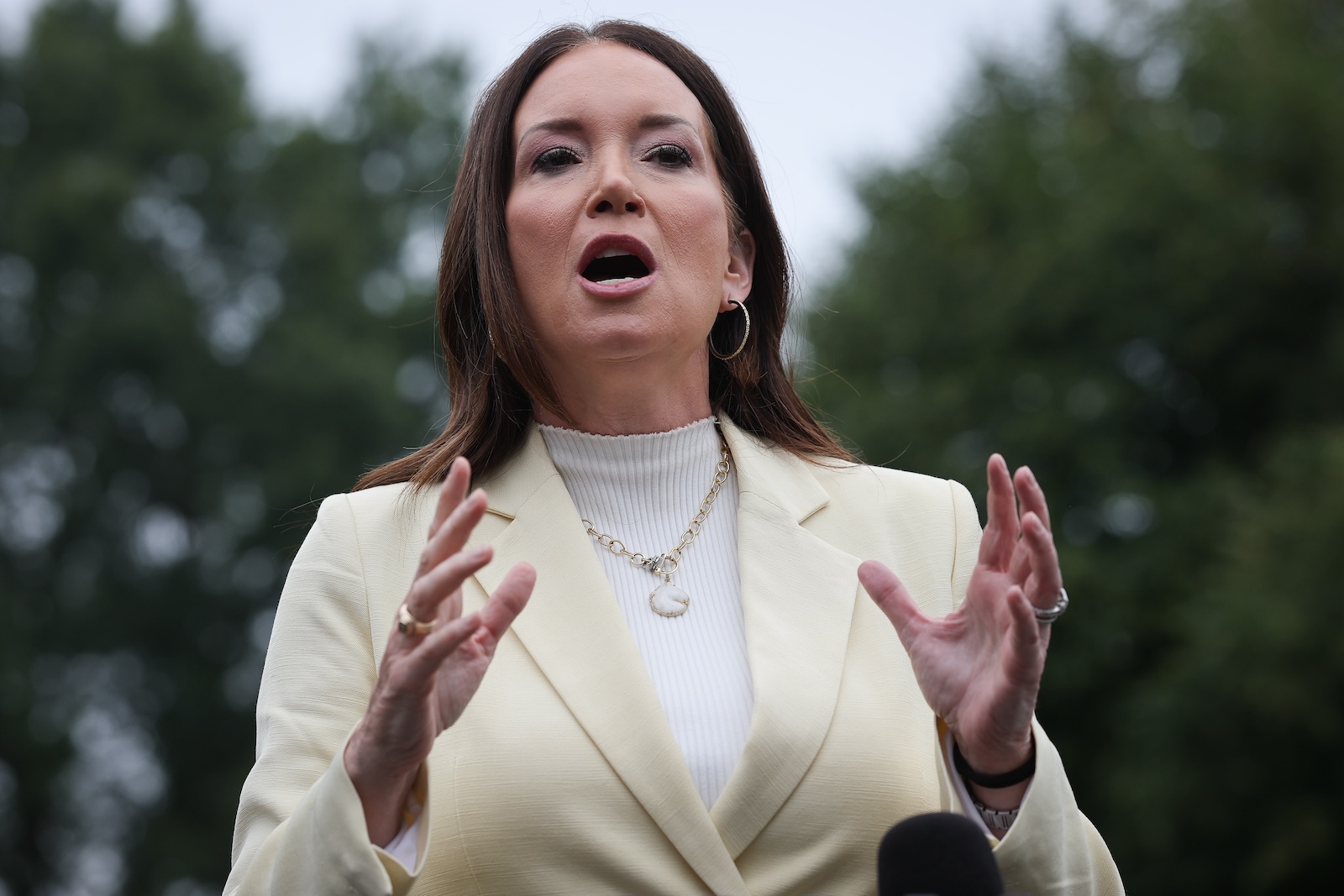

Brooke Rollins, the Trump agriculture secretary, has claimed the administration will create a farm workforce that’s “100 percent American.” But currently, minimum wages for farmworkers are so low that they do not attract very many U.S.-born workers to the agriculture industry, said Edgar Franks, political director for Familias Unidas por la Justicia, a farmworker labor union. “If you’re trying to attract local workers, the AEWR is going to be way too low,” said Franks.

Oliva, at the HEAL Food Alliance, argued that if wages for farm work fall even lower, employers will see a drop in able and willing workers. “What you’re essentially going to see — and this is something I am 100% convinced of — is an even lower participation in the job market,” he said. Franks disagreed. “I still think, even if the wages go down to $10 an hour, people from other countries would still line up to come and work under the H-2A visa,” he said, adding that their economic opportunities are often far worse in their home country.

Despite the grueling nature of farm work, the H-2A visa program — which allows agricultural employers to hire temporary or seasonal workers from abroad — is arguably in more demand than ever. The program was developed in 1986 during the Reagan administration, as part of a broader immigration reform package aimed at cracking down on unauthorized migration into the U.S. It has grown dramatically over time; the USDA found that H-2A certifications tripled from 2010 to 2019. (There is no cap on how many H-2A visas are offered annually.) Last year, nearly 400,000 visas were issued, according to the Farm Bureau.

Win McNamee / Getty Images

If wages for agricultural workers fall, Oliva said, those who do take those jobs may feel pressure to work longer hours to make ends meet.

Farmworkers lack many labor protections at the federal level; for example, they are excluded from receiving overtime pay under the Fair Labor Standards Act. In the absence of stronger labor rules, “workers are discouraged from taking breaks and drinking water because you’re not going to make any money if you’re not working,” said Oliva. That level of physical exertion is dangerous when combined with climate change driving up high temperatures.

Following the USDA’s announcement, the Department of Labor published an interim final rule aimed at adjusting its AEWR methodology — although it’s unclear exactly how the agency plans to do so. (The labor department did not respond to a request for comment.)

This is not the first time that federal agencies under a Trump administration have tried to revamp how seasonal migrant farm laborers are paid. During the first Trump administration, the USDA similarly moved to end the FLS; United Farm Workers sued, successfully blocking the decision.

In her statement, United Farm Worker president Romero said the labor union is committed to “fighting exploitation and deportation at the same time.”

Asked whether the group would sue the USDA over its move to end the FLS a second time, a spokesperson for the union said it was too soon to tell.