At a peaceful health centre in a sleepy suburb of Buenos Aires, Juanita is about to change someone’s life. She’s sitting next to me in her garden office – a small lean-to building, covered with purple jacaranda blooms – her small hands wrapped around a warming cup of maté on this bright but cool morning.

Then the phone rings. When Juanita answers, there’s a panicked voice on the line. It’s a young woman who has just found out that she is pregnant, and she’s desperate not to be. But her circumstances mean that she has no legal recourse to an abortion and cannot see a way out. People in this situation may try to end their pregnancy using ineffective or dangerous methods, which makes unsafe abortion one of the world’s leading causes of maternal mortality.

Juanita radiates empathy as she discusses the situation with the frightened caller. She calmly tells the young woman about a medication called misoprostol that could safely terminate her pregnancy. It’s sometimes called ‘magic misoprostol’ – not only because it is cheap and effective in up to 93 per cent of cases, but also because it can be legitimately sold as a stomach ulcer drug. That means it can be purchased even in contexts where abortion is illegal or difficult to access.

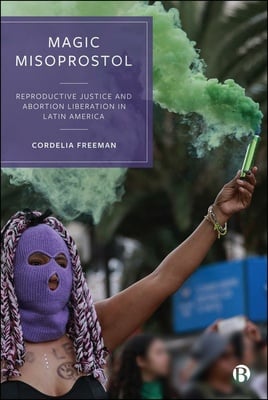

Juanita is an acompañante, or an ‘accompanier’, a person who is committed to helping those who wish to end their pregnancies with safe and supported access to misoprostol. As I argue in my book Magic Misoprostol, it is the work of abortion activists and acompañantes like Juanita who truly make misoprostol magic. This highlights how grassroots activism and community-led support can transform public health outcomes even in restrictive legal environments.

Pharmaceutical company Searle developed misoprostol as a treatment for stomach ulcers in 1973, but subsequently found that it could cause miscarriages. So when misoprostol was first marketed in Brazil in 1986, its packaging included a cartoon image of a pregnant woman with a red line across her body, and warnings that no one should use it when pregnant.

That turned out to be an accidental advertisement. At the time, abortion was completely illegal in Brazil and heavily stigmatised, so misoprostol seemed to offer a new solution. People began self-experimenting with misoprostol until they discovered how to take the right number of pills to induce a miscarriage.

The knowledge that misoprostol could be used to safely end pregnancies soon spread across the continent. But accessing the pill and knowing exactly how to use it remained tricky. This is where activists like Juanita come in. Hundreds and perhaps thousands of acompañante groups exist across Latin America, where abortion is often criminalised. While they vary in their size and organisation, they are all driven by helping people to have abortions outside of the medical sphere, with autonomy, clear information and support.

While from a legal perspective Latin America may seem to be making positive strides, with progressive laws in Colombia, Argentina and Mexico, the reality is more complicated. Some countries, particularly in Central America, are restricting abortion even further and even in contexts where abortion seems possible on paper, there can still be logistical hurdles, stigma and even violence from healthcare professionals that prevent people from being able to access an abortion.

That’s where acompañante groups step in. Acompañantes offer empathy, understanding and support without questioning someone’s decision to have an abortion. This means that for many people, an abortion with an acompañante outside of the medical system is not a desperate last resort; it is their preferred way to end their pregnancy.

Meanwhile, the medical establishment has also adopted misoprostol. Used in combination with mifepristone, it is now the standard way to have an abortion within the first 12 weeks of pregnancy, and has helped millions of women around the world. And it is not just the success of the medication itself. The acompañante model of support has proved so effective that in some countries, such as Argentina, acompañantes have been invited to train medical professionals on how to support people with abortions.

As I listened in on Juanita’s conversation with her desperate caller, I heard her patiently explain the young woman’s legal rights, where she would be able to purchase misoprostol and how Juanita could help her to use it effectively. The caller offered her deep gratitude, and when she hung up, she had a clear plan of her next steps.

Juanita put the phone down and smiled warmly at me. “You have a gift”, I told her. She laughed it off. While this was an extraordinary conversation for me to have the opportunity to overhear, and one which was life-changing for the caller, Juanita has taken hundreds of similar calls.

The story of misoprostol shows that while the development of medication is important, it is the activism and dedication of acompañantes such as Juanita that have reshaped access to essential healthcare, challenged restrictive laws, empowered individuals and reimagined what abortion care can look like. Thanks to them, misoprostol has become far more than a stomach ulcer drug. It has become a life-changing abortion pill that has transformed abortion access across the world.

Cordelia Freeman is Senior Lecturer in Human Geography at the University of Exeter, UK.

Magic Misoprostol by Cordelia Freeman is available on Bristol University Press for £27.99 here and will be publishing open access on September 12.

Magic Misoprostol by Cordelia Freeman is available on Bristol University Press for £27.99 here and will be publishing open access on September 12.

Bristol University Press/Policy Press newsletter subscribers receive a 25% discount – sign up here.

Follow Transforming Society so we can let you know when new articles publish.

The views and opinions expressed on this blog site are solely those of the original blog post authors and other contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of the Policy Press and/or any/all contributors to this site.

Image credit: Colin Lloyd via Unsplash