The recent UN Women’s ‘16 Days of Activism’ campaign against gender-based violence highlighted a global focus on ending digital violence. Although the annual campaign has concluded, its themes remain vital as we move into 2026.

Digital violence is a growing problem affecting women and gender-expansive people, often as a result of their careers. For example, 82 per cent of female parliamentarians and 73 per cent of women journalists have experienced online abuse, with 50 per cent of that happening in response to posts about gender inequality itself.

It’s good to see digital abuse being highlighted as a serious issue because all too often it’s regarded as secondary to offline, physical violence. The effects of digital violence are often felt in quieter, more private ways, but that doesn’t mean words don’t hurt – especially when it comes to music industry careers.

What digital violence looks like for artists

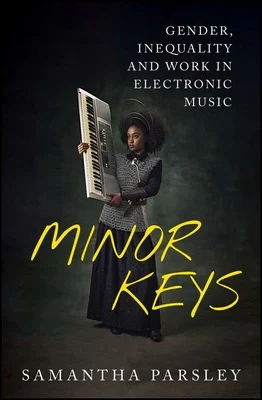

The impact of dealing with online abuse, misogyny and micro-aggressions was a prominent theme in a study I’ve just completed exploring the career experiences of women and gender-expansive electronic music artists. In my book Minor Keys: Gender, Inequality and Work in Electronic Music, I explain how dealing with social media trolls is ‘ameliorative work’.

Ameliorative work is all the effort that minoritised gender artists have to do in order to make their working lives better, or at least bearable just because of their gender identity. It’s work that is over and above their day-to-day activities as musicians, DJs, record label owners, promoters and audio engineers, and importantly, it’s work that their cis-male counterparts almost never have to do.

Ameliorative work is often hidden, almost always unpaid, and is physically, financially and emotionally depleting. This damages artists’ careers.

In the context of digital violence, ameliorative work is required to deal with misogynist – and possibly (re)traumatising – comments on artists’ videos, posts and other online content. Social media is not an optional part of a music career if you want to interact with genuine fans, but essential as a successful marketing tool.

So, it’s almost impossible to avoid seeing the abhorrent comments along with the constructive ones. You can’t ‘unsee’ death, rape and abduction threats no matter how fast you hit delete, and coping with that emotional shock and subsequent visceral wrench takes constant inner work as any therapist will tell you.

Even comments that state you are nothing more than your breasts, have slept your way to success, or – particularly in the case of trans people – should be erased as a human being hit hard, no matter how resilient you are. Regardless of whether they pose an offline threat, such statements are violent because they scream ‘you don’t belong!’ compounding the reality of being an unwelcome outsider in an environment where you are already in a minority.

How ameliorative work limits artistic careers

Building and maintaining the armour needed to be resilient is ameliorative work, as is the very real time it takes to sift content to find and delete offensive comments. This is time that cis-male musicians are using to make music and progress their actual careers, and it’s things like this that are never taken into account by industry gatekeepers when they argue that the playing field is level for all.

Over time, exposure to these messages also damages the self-esteem and confidence that’s central to creative work, reducing the willingness of minoritised gender artists to be visible – for example, refusing to be part of brands’ online campaigns because they’re sick of the backlash that will hit them if they are.

Voluntary withdrawal from online public life damages musicians’ careers at a more structural level too, since representation of diverse artists is essential to normalising different bodies as rightful players in what is otherwise an extremely white, cis and male industry. When diverse folks are seen as normal and not novelties, they attract less attention and (we hope) the trolling reduces. But if diverse artists are not willing to be represented, normalisation takes longer to happen, if it happens at all.

So, what can be done?

The internet is at its most powerful when we come together.

If you see misogynist content, call it out with a comment, or a DM of solidarity to the artist if you don’t feel safe posting publicly. If you run a platform, agency or record label/ community, proactively police your comments sections – don’t leave the ameliorative work to your artists.

In my research for Minor Keys, I witnessed the power of bystander intervention in silencing trolls, but equally important was its power to support artists affected by gender-based digital violence. These powers are amplified when those bystanders are cis-male allies calling out other men.

Tighter regulation of the internet seems to be common area of attention, particularly within the 16 Days of Activism campaign, but to me, activism starts locally, with a small ‘a’. We all have a part to play every day of the year.

Samantha Parsley is a writer, coach, DJ and founder of ‘In the Key’, a directory and platform championing the careers of women, trans and non-binary electronic music producers (www.inthekey.org). She is Professor of Organization Studies at the University of Portsmouth and coaches research-led writers as Curious View (www.curiousview.co.uk). Samantha DJs and produces music as Dovetail and lives with her husband on the south coast of England.

Minor Keys by Samantha Parsley is available for £14.99 on the Bristol University Press website here.

Minor Keys by Samantha Parsley is available for £14.99 on the Bristol University Press website here.

Bristol University Press/Policy Press newsletter subscribers receive a 25% discount – sign up here.

Follow Transforming Society so we can let you know when new articles publish.

The views and opinions expressed on this blog site are solely those of the original blog post authors and other contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of the Policy Press and/or any/all contributors to this site.

Image credit: Zakariae Lahkim via Unsplash