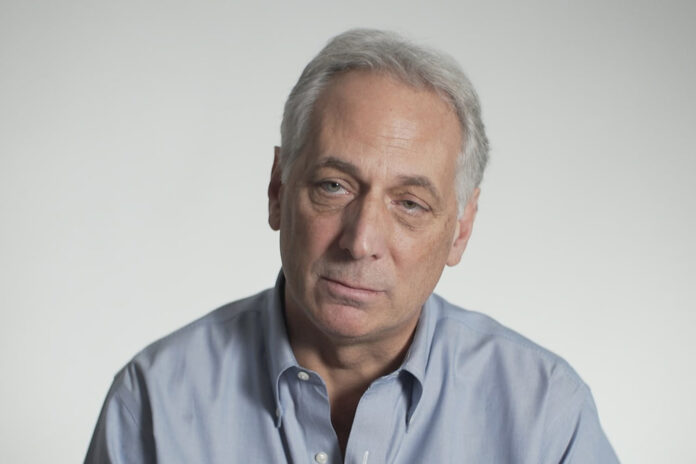

In 2019, James Manfredonia and some of his former Little League teammakers thought they would finally be able to face the coach who claim to abuse them decades ago when they sued him under the law of New York child victims.

Five years later, they have not yet achieved a trial date, and their lawsuit against Tony Sagona remains in Limbo.

The Sagona case is not outlier. For two years, from 2019 to 2021, 10,783 lawsuits were filed under the law of children’s victims in New York on behalf of 14,588 men and women who say teachers, coaches, priests, and other sexually abused figures as children decades ago, according to figures provided by the Unified State judicial system.

Of these cases, 7,632 were attributed to the judges and 2,052 of them were resolved or discarded. The rest is classified as “pending”.

“When the processes began to be archived, there was a lot of attention and talk about how the victims would get justice,” said Manfredonia, 63. “But no one seems to care. Here we are, all these years later, and we just have to wait, wait and wait. How can these cases not be a priority, especially given the supposed effort to pass the law?”

The law of child victims, which the New York Legislature approved in January 2019, raised the status of limitations and allowed childhood abuse victims to seek predators, regardless of when abuse occurred.

Although there seems to be a single reason why the processes are caught in a legal logjam, there is a lot to point out about who the culprit is.

The lawyers say that part of the bottleneck is that only a handful of judges is dealing with all these cases and that the state did not do enough to accelerate the cases. Legal battles ongoing the main institutions, such as the Archdiocese of New York – accused of covering up systematic sexual abuse – and its insurers about who is responsible for paying millions of dollars in settlements has also stopped the cases.

“It’s a typical story,” said Heather Cucolo, a teacher at the New York Law School. “The legislator passes something to correct a wrong. Let’s open this window, they say. We are supporting the victims. But the system to streamline these cases is simply not working, and no one seems to be intensifying to effect and implement the necessary changes.”

David Catalfamo, who leads a victim’s defense group called Just & Compassionate Compensation, said the state did little to intervene in legal battles. He said the state’s financial services department has released guidelines by saying that he expects insurance companies to “fully cooperate with the intention of the child’s victims.”

But in practice, Catalfamo said, Governor Kathy Hochul and the Department of Financial Services “blatantly supported great insurance, abandoning the survivors who promised to protect.”

Hochul’s office did not answer the emails and asked for comments.

Manfredonia’s lawyer, Bradley Rice, said things are moving so slowly, in part, for lack of judges assigned to deal with all cases. He said that to streamline things, some of the processes are being grouped.

“This is something you do in the first year or two after the process is filed,” said Rice. “The state was simply not prepared to deal with all these processes.”

One of the state senators who led the desire to approve the child’s victims law, Brad Hoylman-Sigal, whose district includes much of Manhattan’s Upper West Side, introduced a bill that would increase the number of judges of the state’s Supreme Court. But it is far from becoming law.

“New York has a constitutional limit of the number of state judges from the state,” Hoylman-Sigal’s office said in a written answer to the questions. “We pass legislation to remove this limit, but it makes it demands again through both homes and then approved by the popular vote by the people of New York.”

While Cucolo, a law professor, agreed that the scarcity of judges is a factor, she said there are other problems at stake by reducing the process.

“There is the process of discovery, which takes time. There are confidentiality rules when you are dealing with cases like these,” she said.

According to the child’s victims law, there is a process whereby victims should reach a “incident -specific threshold,” Cucolo said, adding that the process can take some time.

In addition, the delay agreements are ongoing battles between the processed institutions and their insurance companies to determine who is responsible for payments, say Cucolo and the defenders of the victims.

The Archdiocese of New York was in a battle with its insurer, Chubb, who must pay claims. The Archdiocese has been the target of more than a thousand actions of children’s victims, accusing it of having kept an eye on the sexual abuse of children by priests for decades.

In September, after he sued Chubb, claiming that he filled New York General Commercial Law, Cardinal Timothy Dolan, the Archbishop of New York, accused a letter to his flock that his longtime insurance company was “trying to escape his legal obligation and contractual morals to settle the covered claims that would bring peace and curars to the vimitaris.”

Dolan, who opposed the law of children’s victims in the past, argued that paying approximately 1,400 open claims would bankrupt the church.

Meanwhile, the Archdiocese has established its own independent reconciliation and compensation program to help victims who opted not to sue. In April, the Archdiocese had settled more than 430 of these cases, said the Joseph Zwilling -Voice port.

An Archdiocesan lawyer said in a statement on Friday: “The archdiocese and associate policyholders sought help to its longtime insurer when abuse survivors brought CVA allegations claiming that they hired negligently, supervised and maintained certain individuals accused of abuse.

Chubb, who held the archdiocese from 1956 to 2003, He said on Friday in a statement in response to questions from NBC News that “compensating victims who have suffered sexual abuse of unbridled church for decades should be the main priority of the archdiocese, especially since they are sitting in a large amount of wealth.”

“Nothing is preventing the archdiocese from paying its victims today,” the statement continued. “We have tried for years to obtain information on individual claims, but the archdiocese refuses to cooperate or provide any information. They continue to hide what they knew and when, which is why, in an attempt to force the release of information about claims that we processed it in June 2023.”

In closing, Chubb added, “You can’t get insurance coverage for what the church admitted – hiding and facilitating the criminal sexual abuse of children.”

But even cases against smaller organizations – such as Manfredonia against her former Sagona Book, Babe Ruth’s big league and others that the complaints claim that the coach was attacking boys, but did nothing to prevent him – they are being kept.

Sagona, who is 74 and lives in Boca Raton, Florida, was not accused of a crime. His lawyer, Steve Kirk, said Sagona “continues to deny the allegations with all his heart.”

“He never trained the Little League and doesn’t even know some of the people who are suing him,” Kirk said.

The calls to a number for the great Babe Ruth League killing were not answered.

But there may be good news: Rice has been informed that soon it will be receiving a court date, but it is unclear when. However, he said, the process is taking too long.

Manfredonia said that despite the delay, he does not regret having filed the process. Just being able to talk openly about something he kept bottled for decades is his own reward, he said.

“The biggest benefit of going out and telling our story is that it helped our families understand why we are the way we are,” he said. “They really don’t know how to know what it is, they know what we are feeling and hiding all this time. But they can start to understand our behavior and reactions, and this is a great benefit, a great benefit.”