Why are liberation and independence movements so often betrayed when their leaders get into power?

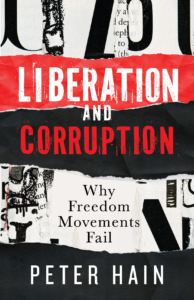

In this episode, Richard Kemp speaks with Lord Peter Hain, author of Liberation and Corruption, about this uncomfortable question.

They discuss Peter’s involvement with the fight for Nelson Mandela’s freedom, the reasons why liberation movements from ANC to the Sandinistas have corrupted once in government, and what we can all do to combat corruption and stop this vicious cycle.

Available to listen here, or on your favourite podcast platform:

![]()

![]()

![]()

Lord Peter Hain served as MP for Neath (1991-2015) and held senior roles in the UK Labour Government for 12 years, including seven in the Cabinet.

Scroll down for shownotes and transcript.

Liberation and Corruption by Peter Hain is available for £19.99 on the Policy Press website.

Liberation and Corruption by Peter Hain is available for £19.99 on the Policy Press website.

Bristol University Press/Policy Press newsletter subscribers receive a 25% discount – sign up here.

Follow Transforming Society so we can let you know when new articles publish.

The views and opinions expressed on this blog site are solely those of the original blog post authors and other contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of the Policy Press and/or any/all contributors to this site.

Image credit: Gregory Fullard on Unsplash

SHOWNOTES

Timestamps:

01:37 – How are liberation movement who come into power affected by their predecessors?

03:59 – Who were the Sandinistas? What did they want? And how did they go so wrong?

07:27 – What role did the US play in the corruption of Nicaragua and quite a lot of Latin America?

09:40 – How does the UK participate in theft from the African continent?

18:06 – What is neoliberalism, and did it contribute to Robert Mugabe’s descent into corruption?

22:03 – Is there a link between neoliberalism and the rise of the far right and the populist right?

26:13 – How correct was Mandela when he said that those who fought corruption could become corrupt themselves?

29:26 – Could you tell us about your involvement with campaigning for Nelson Mandela’s freedom?

32:34 – What lessons should our governments and policymakers learn from liberators who come into power?

Transcript:

(Please note this transcript is autogenerated and may have minor inaccuracies.)

Richard Kemp: You’re listening to the Transforming Society podcast. I’m Richard Kemp, and on this episode I’m joined by Peter Hain, former MP for Neath from 1991 to 2015, part of the UK labor government for 12 years and now sitting member of the House of Lords. Born to South African parents exiled for their anti-apartheid activism, Peter has been a lifelong activist and politician with over 50 years experience battling corruption.

In industry and in government, corruption is rampant. If there was some way to gather all the money stolen through corruption in just one year, you’d be able to feed the world’s hungry 80 times over. Peter’s new book, from which I got that figure, is titled ‘Liberation and Corruption: Why Freedom Movements Fail’ and is published by Policy Press. In it Peter examines global examples ranging from Africa to Latin America, Russia, the Caribbean, China and India to ask why independence and liberation movements are often betrayed when their leaders get into government.

As early as his teens, Peter led campaigns against apartheid, surviving a letter bomb and an attempt to frame him for bank robbery, and later became a major force in the struggle to free Nelson Mandela. In this book, with the unique perspective of having navigated both the streets of protest and the corridors of power, Peter reflects on the challenges of staying true to the values of liberation struggles while confronting their disappointing outcomes.

Peter Hain, welcome to the Transforming Society podcast.

Peter Hain: Thank you very much, Rich.

RK: Thanks so much for coming on. It’s such an important book. I’m really, just really pleased that we get to discuss your book today. Towards the end of it. You say liberation movements never came into government in a vacuum, able to begin afresh. They had to start where they found themselves rarely, if ever, where they would have chosen to be.

This statement, it really hit me as it felt quite key to your book. Can you explain how it relates to the liberation of subjugated peoples and then the corruption that follows?

PH: Yes. Well thank you. And it was one of the issues that I investigated because I’d been haunted as a protester in favour of these liberation struggles, notably, Nelson Mandela’s African National Congress, struggling for freedom and democracy against a brutal apartheid state, but also other liberation struggles like the Sandinistas in Nicaragua. And I was really disturbed by the way that they all seemed to get corrupt.

And when I looked at it, part of the explanation, it’s not an excuse. There is no excuse for playing with the devil, of indulging in corruption by anybody, whatever the color of their skin, wherever they are in society. But what I discovered was that when you come to understand the circumstances in which liberation movements come to take power, get into government, get into office themselves, what you find is they take over a system that is deeply corrupted itself.

So in the case of apartheid, that was a corrupt state. It was not only brutal, but it was corrupt. There were all sorts of shenanigans going on in the defense industry, for example, and lots of cozy contracts in which people were able to make money. Sanctions had been applied by the international community, and so those in the oil industry, for example, were able to easily earn money on the side by evading those sanctions.

And so when Nelson Mandela’s African National Congress actually took over the power, the reins of power and entered government, they found themselves embedded in the state. And he warned about it publicly as president. But that didn’t stop a lot of his colleagues, sadly, in going about things in the way that their former oppressors had done, and exactly the same thing happened in Nicaragua to Daniel Ortega’s, who was the leader of the Sandinistas, to his liberation movement.

RK: You mentioned the Sandinistas in Nicaragua. So the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, they were a liberation movement. They took office in 1979. By 2023, Nicaragua was the second poorest country in the Western Hemisphere. You say that exports collapsed. Inflation surged at one point to as high as 30,000%. Couldn’t get even get my head around. Like what, what that would look like.

Who were the Sandinistas? What did they want? And how did they go so wrong?

PH: Well, Sandinistas were a liberation movement led by Daniel Ortega. He was a pin up in student unions and in my youthful activist days in the 1970s especially. Not ever as globally important and iconic a leader as Nelson Mandela, but nevertheless a very admired figure. And they were struggling, and he was fighting against a brutal fascist state, often propped up by the US government.

And as a result, against a background of Spanish colonialism, which is, by the way, a very important part of the picture, as well as to why things go so wrong. Because not only were the states themselves corrupt like the apartheid state or the fascist state in Nicaragua, but in Nicaragua’s case, there was a very corrupt colonial empire ruled by the Spanish colonizers in Latin America, South America, Nicaragua, for example. In South Africa, it was the British colonialism, mainly that preceded apartheid and which also infected the whole society with corruption.

So when Nicaragua experienced such terrible economic problems under the Sandinistas, you also have to look at the culpability of the global financial and economic system in which they found themselves trying to govern. So they began with noble objectives of spreading justice and spreading equality and creating more opportunities for everybody, and not just the ruling elite. And they quickly found themselves entangled in a global economic and financial system that was seeking to take power from Nicaragua and keep it where it had always been under the fascist elite and, before that, under colonial rule was concentrated in the big global corporations and banks that had dominated the scene.

RK: Can you give a little bit more about who the Sandinistas were revolting against when they first took power? Because that kind of set the scene in like what it was like before they took over in 1979.

PH: Well, the Sandinistas were a popular liberation movement with all sorts of allies of workers, peasants, trade unionists, people in civil society objecting to the brutal fascist regime which had ruled Nicaragua for a long time. And so they were not just a liberation movement, but rather like Mandela’s ANC in South Africa, they had allies in the wider society, and they were struggling to abolish poverty and massive inequality and corruption and injustice and brutal power exercised by a tiny elite and establish a democratic state.

And those with the noble credentials and noble objectives which we all at the time supported. But they were quickly abandoned sadly, in government, which is partly, the theme of the book is why this happens.

RK: How rampant was the US’s, kind of the US’s hand in corruption, both in Nicaragua and quite a lot of Latin America.

PH: The US’s role is very murky and very dodgy and, pretty terrible, frankly, in summed up by one of its leaders saying of an evil dictator in the South American subcontinent. “He may be a bastard, but he’s our bastard.” In other words, he, this dictator, may have been regarded as an evil dictator which he was in this case.

But at least he was somebody that the Americans could work with and pursue their commercial, mainly, interests and security interests through. And that was true in Guatemala. It was true in Bolivia. It was true in other Latin American countries like Nicaragua, and Colombia as well. So it’s a wider pattern of not just a history of mainly Spanish colonialism being brutal, but also creating massive inequality and being in, and embedding corruption.

But it was also the United States governments seeing the subcontinent as being in their backyard as the North American country. And then you have South America, Latin America to the south. And feeling that they needed to control that in order to protect their economic and security interests. So that was their motivation. But it was a pretty nefarious role throughout modern history and still continues.

You look at what’s happening in Venezuela at the moment with President Trump making all sorts of bellicose threats. That’s not to defend the existing Maduro regime in Venezuela, which is itself deeply problematic and seems to be behaving in a very aggressive way towards its opponents, which is totally unacceptable to a Democrat like me. But, you find that the US has continuously, throughout the story, exercised as a, as I say, a pretty disreputable role.

RK: Stereotypes about rich, mainly white countries being uncorrupted in comparison to poorer, mainly black and brown countries has been proven to be false. In fact, you say that Global North countries actively fuel corruption. $100 billion is stolen from Africa every single year, which constitutes a quarter of the continent’s GDP. How does the UK, as an example of this, participate in this theft from the African continent?

PH: Well, mainly by being the conduit for the looting that takes place. Mostly, I might add, by African leaders themselves and elsewhere in the world, local leaders such as in Nicaragua, they don’t tend to invest their looted proceeds in their own countries. They tend to move it through the digital banking pipelines mostly owned by the British, the US and other countries in the Global North into what is seen as safe havens.

So, for example, Britain and London in particular is the center for about 90 billion USD a year, a year, of looted assets to be invested either in property, as a lot of them are, the London property market places, properties in Kensington and Chelsea and Mayfair and so on, as well as the home counties around London are very often bought up by these kleptocrats, with their stolen proceeds stolen from local taxpayers in countries like Africa.

But this 90 billion USD a year, each year, is often then passed through London. Money laundered through London and goes into UK overseas territory like the British Virgin Islands, Belize, Gibraltar and elsewhere. So these are UK overseas territories. They’re often invested into what are called shell companies, in other words, front companies hiding their beneficial owners, their real owners.

This was the kind of thing that happened in South Africa under former President Zuma and his cronies, the Gupta brothers, an Indian family, an Indian originated family who settled in South Africa and worked with Zuma to loot the country on a prodigious scale. Their money went out of the country into London through HSBC, through Standard Chartered Bank, both international banks and through the Bank of Baroda, which is partly owned by the Indian government.

So what you see is a picture here of, mostly white countries, but not exclusively in the Baroda bank’s case, it’s India. You’ve got China involved in all of this through Hong Kong. Hong Kong is one of the main money laundering centers of the world. Originally a British, part of the British Empire. And then you’ve got Dubai, another money laundering center inside the United Arab Emirates.

So the UAE government is complicit. And so when you look at, the point that I make in the book and what you’ve sought clarification on is it’s not just a question of black people being corrupt, they’re no more corrupt or less corrupt than white people as, as it happens. But it is a picture of, yes, where there are corrupt kleptocrats in African countries and there are far too many of them.

They don’t keep the money there. They send it into countries through the international financial system like Britain and elsewhere. So everybody’s involved, and everybody’s complicit in that. And unless the international community, it’s, one of the points I describe and look at in my final chapter, unless the international community as a whole and that means the governments, not just of London and Washington, D.C., but also of Beijing and Delhi and Moscow and Abu Dhabi, and the rest cooperate together to fight this.

You’re still going to see 4 trillion U.S. dollars a year, money laundered and corruptly looted from countries across the world. It’s got to be a global fight or you can’t win it.

RK: That’s an insane amount of money. I can’t I can’t even picture how much money that is.

PH: It is. It’s very difficult to get your head around when you’re talking about billions of dollars, let alone trillions of dollars. I mean, how do you even begin to imagine that. But that’s why when you quoted as a fact taken from the book, that the money looted is equivalent to feeding the world’s hungry many times over.

You start to get a picture of what it could mean if we stop this happening.

RK: So I mean, the way you’re saying, well, this is happening just like kind of matter of factly, it’s quite infuriating to hear, really, that this is all, as a matter of fact, occurring. The international community won’t do anything about it. So if kind of like our policymakers, our leaders aren’t going to do anything about it. Then what should we do about it?

PH: Well, one of the things that can be done is to be, is to set up an international anti-corruption court. Now, there are international courts. There’s an international criminal court, and there’s an international court of justice. But they’re focused on things like war crimes and genocide and that kind of thing. They don’t deal with corruption. You need a court specifically to deal with corruption.

It won’t stop it happening any more than courts, you know, in a country like Britain, stop criminals continuing to conduct their, you know, to go about their nefarious business. But it is a deterrent and if they’re caught, then they can be tried and locked up in the case of criminals. And the same principles should apply, in my view, to looters and kleptocrats.

It won’t stop corruption because that’s, you know, something that requires a multifaceted effort, but it will act as a deterrent. And even in the case of a country, and I imagine Putin’s Russia would never sign up to such a court if it were established. And the US has certainly never supported these multilateral institutions. So this is not just an anti Russian kind of accusation.

But even if the dictators like Putin and others around the world said they wouldn’t allow their countries to sign up because they’d be worried themselves. I mean, President Putin is deeply corrupt himself, having amassed a massive amount of money. Then they would be, they would be prevented from traveling to countries which had signed up. So you, for example, when the G20 summit was hosted in South Africa recently, President Putin was eligible to attend it as a head of government and as one of the G20 heads of state.

But he didn’t because he could have been arrested, not necessarily by the South African government, which is shamefully, in my view, cozied up to him rather, but actually by civil society. So there’s a deterrent there. So he was unable to travel. He would have liked to have done. And the same is true for other kleptocrats around the world. They their own countries may not have signed up to an international anti-corruption court, but there would be various bars on them traveling because if they did, they could easily be arrested.

So it’s a deterrent. And what’s important about it so far, and I described this in the last, again in the last chapter of the book is that it is not something that has been conceived of by Global North figures, including me, though I’m South African by origin, and exiled under apartheid as a child of my anti-apartheid parents.

But this is a this is a court supported by all sorts of countries right across the world. And in fact, there is now a draft treaty which has been drawn up by eminent jurists from all sorts of countries, from South Africa to Ecuador, from the Netherlands to Canada. And scores and scores of prominent lawyers have got to work on a voluntary basis to draw up a draft treaty.

So it’s not like the governments of the world, including our own British government, don’t have something to work on, or are starting fresh. They’ve got a draft treaty that they could quickly start getting support for and get implemented.

RK: Robert Mugabe was an anti-colonial revolutionary who, after becoming president of Zimbabwe, became a corrupt and repressive extractionist. You say that a key factor in corrupting freedom fighters once they reach office has been the voracious impact of neoliberalism. What is neoliberalism, and does it have anything to do with Mugabe’s descent into corruption?

PH: Robert Mugabe is a very sad example of one of the themes of my book. A brave liberation hero imprisoned under the racist regime of Ian Smith for many years, suffered a lot and then came to power and instead of maintaining the values of the liberation struggle and justice and equal opportunities and spreading equality and conquering poverty and so on, he becomes the very opposite, an authoritarian president, a dictator who won’t accept, even when he’s defeated at elections as he was periodically.

They just rig it, afterwards. And that has continued under his successor, Emmerson Mnangagwa, who was his enforcer. And so Zimbabwe is a very corrupt state. Why neoliberalism as an international economic system is important in this, however, is because it’s a form of economics that began, and it’s often sort of denoted as coming to prominence under President Ronald Reagan in the United States and Margaret Thatcher, British prime minister in the UK, around about the early 80s, because they preached privatisation, outsourcing, public is bad, private is good.

And what it’s seen replacing the old post-second World War Keynesian system, which had a flourishing market economy alongside huge record public investment and an extension of public services on the basis that, you know, a flourishing business sector needs educated, skilled people, healthy people. Therefore, good education, well-funded educational systems and well-funded health systems, for example, as well as research and development that provides the seed corn for a lot of our technology for the private sector to bring to market.

A neoliberal system has widened inequality, has cut back on public services. We’ve seen austerity notably here in Britain for 14 years between 2010 and 2014, massive austerity which has left the country in a bad way. Whether it’s potholes in the road or shortage of nurses or doctors or school budgets being very tight and so on. So why that is important to countries like Zimbabwe is it’s massively widened inequality and it’s opened up opportunities for people who are tempted, like the Zimbabwean ruling elite, to enrich themselves.

And then often to move their assets abroad and sometimes bring them back in concealed and so forth. So the neoliberal economic system is not an excuse for people to say, oh, well, it’s nothing to do with me, it’s the international economic system. It does not justify Mugabe and his clique and the current government and President in the Zimbabwean state, from continuing to loot and murder, and enrich themselves at the expense of their poverty stricken people.

It does not excuse that at all, but it does help to explain why it’s happening. Another answer that I was searching for having been haunted by this tendency of liberation movements to become, to lose their way and forget about their values in government. And to explain why this has happened.

RK: We have big global leaders, for example, like our president Donald Trump in the US and kind of like how a lot of his kind of attraction for voters is about like, he could help me kind of pull myself up by my bootstraps and make me rich too. Look at how rich that guy is. He has ideas to help the rest of us working people become rich.

I kind of see it, see it with like our own version or our, like, Diet Coke version. Nigel Farage at the moment as well, kind of the way he’s preaching to his people as well. But like does the popularity of those kinds of people making those kinds of promises does that, is there a line from neoliberalism to those leaders or speakers at least?

PH: I think the rise of the far right and the populist right, and remember that what you’ve seen is not just the election of President Trump in America and the rise of Reform and Nigel Farage seen as a possible future British prime minister. But you’ve also seen this phenomenon happening right across Europe, where the parties of the center left label, the socialist parties and the parties of the center right label, the small c conservative parties, Christian democrat parties have been vanquished by populist movements.

And so, for example, it’s predicted that the far right in France will succeed President Macron, who’s a centrist candidate. And one of the reasons for this, it seems to me, is the neoliberal responsibility, which has been to create massive inequality. But it’s a different type of inequality from the past. You’ve always had the poor sadly being forgotten at the bottom, but what you’ve had under neoliberalism, and this had been shown by a number of authors, Joseph Stiglitz, for example, in the United States, the United States economist has written about this.

Under neoliberalism you see massive inequality. But the important thing about it is the top 10% have done very well. The top 1% have done extraordinarily well. The top 0.1% stratospherically out of sight well. However, what has happened to the 90%? That’s the great bulk of people, not just working class but middle class and including of course the poor at the very bottom. That 90% has either stood still in its living standards in the age of neoliberalism or fallen behind.

And once you hit the middle of society, that becomes very politically disruptive. And you’re in for turbulence, which is exactly what’s happened. You saw that at its most extreme under the post First World War, Weimar Republic in Germany, which opened the door to Nazism, where the middle classes, where there was rampant inflation, people were, you know, going to a supermarket with a barrel load of Deutschmarks and finding that when they got there they needed another barrel.

So you saw the whole fabric of the middle of society being destroyed. Now, you haven’t got that extreme situation in countries like Britain and the European continent and the US. But you have had the middle of society feeling deeply, deeply disillusioned and cheated. And that has given the, opened the door to populists like Trump, like Farage, like the AfD in Germany and all sorts, Marine Le Pen in France and all sorts of other populist right movements to come in with easy answers, often scapegoating people, whether it’s Jews or Muslim or black people as being responsible somehow for the wider ills of the inequality that is visited upon them by the neoliberal system.

So that’s my view as to why we’ve got this phenomenon. That’s also my view as to why you’ve seen almost every liberation or independence movement finding its original values perverted and forgotten or betrayed once they get into power.

RK: You quote former president of South Africa Nelson Mandela in a speech from 1998. He said, “We have learned now that even those people with whom we fought the struggle against apartheid’s corruption can themselves become corrupted.” How true for South Africa has Mandela’s 1998 pronouncement become?

PH: Sadly, far too prophetic for comfort. He was president then. He’d served four years and was beginning the end of his five year tenure when he stood down voluntarily, by the way. A pretty unusual thing for a president to do, especially in Africa, but right across the world. He could have served another term and then kept extending it, no doubt like Robert Mugabe did.

But he didn’t. He said, I’ve served my purpose. I’ve created the basis for a new democracy and now it’s for others to take over. And of course, he was an older man at that stage as well. Not that that’s always a deterrent, by the way, to dictators continuing to keep themselves in power. Mugabe being an example. He stayed on until his early 90s, before he was finally deposed and then died soon afterwards.

I think that warning by Nelson Mandela was both brave, but also prescient, because what he identified was that already, within years of taking office, a few years of taking office, some of his party already looking to enrich themselves, then you’d have to start asking why, and you have to start recognizing that a lot of these freedom fighters, as they were called, liberationists as others might describe them, had been campaigning for change, had been fighting for change and risking their lives in many cases facing brutal regimes with nothing.

They didn’t have jobs. They didn’t have pensions. They didn’t have houses. Suddenly they get into office and they become members of parliament, even more important government ministers, or could be as important senior civil servants in these administrations, suddenly they’ve got access to proper salaries, pensions, houses and so forth. And yet they may be reasonably advanced in their age.

And so they got quite a lot of catching up to do. And so there’s a sense of entitlement that some people feel that they’ve struggled so hard, risked so much, sacrificed a great deal, why should they not benefit personally?

And that is something that Mandela could see happening, which he thought was wrong because he could see in that the seeds of the betrayal that Zuma, one of his successors, celebrated in his ten years of power, epitomized by looting on a prodigious scale and bankrupting the, near bankrupting the country, tragically, literally stealing from taxpayers on a massive scale. Billions and billions of South African rand. Hundreds and hundreds of millions of US dollars or pounds sterling. So I think that what Mandela was pointing to there was actually a pretty salutary trend that I find in my book happened right across Latin America, Africa, Asia, wherever you find independence or liberation movements getting into office, sadly, the story doesn’t end well.

RK: Would you like to talk a bit about your involvement with campaigning for Nelson Mandela’s freedom?

PH: Well, I was part of the British anti-apartheid movement. My parents having been brave, white anti-apartheid activists alone in the family or amongst their circle of friends or alone amongst any of my school friends parents in being jailed, issued a banning orders and ultimately my father prevented from continuing to work as an architect, which led us to be forced into exile and coming to live in London from Pretoria, where we’d lived.

And that led me into the anti-apartheid movement in Britain, where my parents, having worked with Nelson Mandela in the late 1950s and before he was imprisoned, and my mother having been to his first trial in Pretoria, the only white person to, normally to attend his trial, the black public gallery, because everything was segregated under apartheid in those days, had been absolutely packed with his supporters.

They knew him, but I didn’t get to know him personally until after he was released from prison, and by which time I was a member of Parliament in my early 40s. And then I had the privilege of working with him and getting to know him as a friend. But he was the symbol of the anti-apartheid struggle in Britain.

It was his personality, his picture who was adorned protest placards that I held up, for example, outside South Africa House in Trafalgar Square, when it was then the embassy of Apartheid in London. Now, of course, it’s the embassy of the High Commission of a democratic government, with all its imperfections, a massive change. I worked for his freedom.

Not as for one person’s freedom, but as the symbol of a wider movement. Of course, he served 27 years of his life, the best years of his life in prison, most of them on Robben Island, a cold, bleak enclave, on an island in a very cold sea outside Cape Town. So, he was the symbol of the movement.

And people might or might not remember the great concert at the old Wembley Stadium attended by 100,000 people. The Free Nelson Mandela concert on his 70th birthday in 18, sorry, in 1988. And that was broadcast. It was, on stage with some of the biggest rock and pop stars of that era. And those, their songs and their performances were broadcast to hundreds of millions around the world.

And that made Mandela an even more well-known, iconic figure. So he became it’s quite important, just as Daniel Ortega was in a much lesser way, because nobody could rival Mandela, and for the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, you need people that people can identify with, that they can relate to as individuals in order to symbolise a cause. And Mandela certainly was that for all of us.

RK: In your book, it is a bleak picture of corruption, but there’s also hope in your book as well. And you’ve touched on quite a bit of hope already today. And I was wondering if you could offer a bit more, if you don’t mind. What lessons should our governments and policymakers learn from liberators who come into power?

PH: Well, first of all, our governments and politicians should stop simply talking the talk about opposing corruption, as they all do. All of them, pretty well, and start walking the walk. And that includes here in Britain. We all say, and we’ve got legislation that is admirably against corruption and money laundering brought in, including by the last conservative government, which I vigorously opposed.

Not that policy, but their wider policies. Whether it’s US politicians or British politicians or French politicians or German ones or Spanish ones, wherever it is in the world. And you would even find Indian politicians. I’m not sure about Russian ones, but, and maybe Chinese politicians all say they’re against corruption, but actually they turn a blind eye to it.

They don’t resource the Serious Fraud Offices, the National Crime Agency is the main, some of the main British enforcement institutions and their equivalents across the world. They don’t resource them properly. And as a result of which they can’t actually combat these international global criminals and looters and money launderers on the basis that and with the kind of power that’s needed.

So I think you’ve got what we can all do is demand more from our politicians. What we can also do in our own lives, I think, not try to be saints because none of us are, but actually making sure and I’ve said this in a speech in South Africa where corruption is a result primarily of the loot, the Zuma decade, but not exclusively, is now deeply embedded throughout the society.

Unless you stand up and say, no, I’m not going to pay a policeman who stops me on a spurious traffic offense because he wants to be paid some cash. Or, in South Africa’s case, the home or the interior affairs, the home affairs official who won’t give you a permit or a visa, unless you pay a bribe or I even discovered to take a driving test in parts of South Africa, you have to pay the driving instructor a bribe to take the test.

Whether or not you know you pass or not, to actually take. So unless citizens start saying no, I’m not going to pay that police officer. It’s not an easy thing to do. It’s easy thing for me to say. And when I made the speech, I said, I’m going to get on a plane and go back to London after this, it’s easy for me to say, I’m not living here.

But unless the ordinary citizens of the world say, no, we’re not going to put up with this, then it’s not going to change. But I think there’s another lesson that I end up with in the book that I kind of came to understand more clearly. If I didn’t so much before. And let me put it this way, that the struggle for democracy and justice and in this case, against corruption is a never ending one.

Too many of us thought when apartheid was defeated and vanquished. And you had a democratic, the first democratic election ever in South Africa’s history in April 1994, which I found it very emotionally moving. I was a British parliamentary observer. We thought that was job done. And actually it’s a beginning of a different form of struggle. And unless new generations say we’re going to keep fighting for these values, we’re going to keep demanding and getting involved in civil society groups, for example, saying no to corruption, no to inequality, no to injustice, yes to equal opportunities, yes to social justice, yes to opportunities for all.

Unless each person says no, you can’t just say because women have got the vote therefore the battle for equality for women is over. Just because there are laws protecting gay people doesn’t mean to say that the position of gay people is what it should be. Just as it’s not enough to say because you got the vote, you’ve got a democracy.

No, it isn’t sufficient. You’ve got to keep the spotlight on politicians. You’ve got to keep holding them accountable. And I speak as a lifelong politician. You’ve got to keep the struggle up. So the book ends with a message to everybody that actually this is a never ending process. It’s up to fresh generations to hoist the banners and take up the cudgels and demand something better for all of us.

RK: Thank you, Peter, so much for coming on the Transforming Society podcast today. Giving your time and discussing your book. It really is an important book. I’m going to let everybody know where they can find your book in a moment. But first, just wondering if there’s anywhere we can find you online.

PH: Yes, you can find me online. And thanks for, thanks for hosting this podcast. You can find me online at the parliament website. You find my email, it’s publicly available. My own website is peterhain.uk. I’m on a lot of the social media platforms X formerly Twitter. My granddaughter runs my TikTok and Instagram accounts. You’ll find me on there as well.

RK: Thanks, Peter, and thanks to your granddaughter for all her service as well. ‘Liberation and Corruption: Why Freedom Movements Fail’ by Peter Hain is published by Policy Press. You can find out more about the book by going to policy.bristoluniversitypress.co.uk and also transformingsociety.co.uk.