A large-scale study of European rivers detected 504 harmful substances — 175 of them pharmaceuticals like painkillers and antidepressants.

Concerns about immediate and longer-term environmental and public health impacts are mounting. So far, micropollutants occur at concentrations too low to harm humans taking an occasional swim. But it’s a different story for aquatic organisms, from small snails to large fish, which are constantly exposed to pharmaceutical and other compounds that are known to affect fertility, trigger sex changes, impair navigation and movement, or increase mortality.

In response to the increase in micropollutants, the E.U. passed a revised Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive, which went into effect in January. It mandates that thousands of medium and large plants across Europe begin planning and installing, between 2027 and 2045, a fourth step in the purification process. According to planning documents, such “quaternary” treatment would slash levels of micropollutants by at least half using technologies like ozonation and activated carbon filtration.

While Switzerland and some regions in Germany and the Netherlands have already taken the lead, the vast majority of sewage plants in Europe — and in the United States — still lack advanced treatment technologies. The hugely expensive upgrades mandated by the E.U. will mainly be funded, according to the directive, by polluters themselves. But lobbying groups for the pharma and cosmetics industries in Brussels and in other European capitals, as well as individual companies, are fighting fiercely against the new rules.

Water before (left) and after (right) a fourth stage of purification at a wastewater treatment plant near Frankfurt, Germany.

Lando Hass / dpa

Despite stricter regulations and better wastewater treatment across Europe, the U.S., and in other parts of the world, tens of thousands of industrial chemicals, pesticides, and pharmaceutical compounds now circulate widely — many ending up in rivers through factory discharge or sewage plants. Together with pesticide runoff from agricultural fields, industrial discharges, and runoff from streets, urban wastewater is a major cause of what Ralf Schulz, an ecotoxicologist at the Technical University of Kaiserslautern-Landau, in Rhineland-Palatinate, describes as the “chemization” of aquatic habitats. A large-scale 2024 study by chemist Saskia Finckh from the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research in Leipzig screened rivers across 22 European countries, detecting 504 harmful substances — 175 of them pharmaceuticals like painkillers and antidepressants.

One of those painkillers, diclofenac, can accumulate in animals and damage the livers of river otters and the kidneys of fish, leading to increased mortality. Elevated levels of the drug were found in roughly three-quarters of surface water samples taken in Germany, according to the country’s Environmental Protection Agency, or UBA. More and more scientific studies are documenting negative effects of wastewater compounds on fish, crustaceans, algae, and even human immune cells.

“There’s no doubt who has to pay for [advanced treatment],” says a Berlin official. “The industries that cause the pollution.”

Public health officials fear that contaminants will increasingly find their way into drinking water, making it less safe for consumption. Berlin, like many cities around the world, sources most of its drinking water from wells near its rivers and lakes, after it has naturally filtered through layers of soil. So far, Berlin’s drinking water is well below threshold values for the 50 medical substances that are regularly screened. At the Tegel Lake well, however, levels of a transformation product of blood pressure drugs are already above the threshold recommended by UBA for safe lifelong consumption. Gerhard Mauer calls permanently keeping micropollutants out of drinking water “our duty under the precautionary principle.”

That’s why, on a crisp and sunny day in late September, Mauer proudly showed the company’s newest construction project to Andreas Kraus, Berlin’s permanent secretary for climate protection and environment. Scheduled to open in 2027, the Schönerlinde plant will use ozone, synthesized on site, to break down many of the harmful pollutants that have been evading purification. This project puts Berlin at the forefront of a technological revolution in sewage treatment. “Once this facility is operational,” Mauer told Kraus, “the water we pump into Tegel Lake will be largely free of problematic chemicals, and we can extract drinking water without having to worry too much about them.”

The new facility under construction at the Schönerlinde wastewater treatment plant will use ozone to break down micropollutants.

Sven Bock / Berliner Wasserbetriebe

A lot of money is at stake. During Kraus’ visit, Mauer said that equipping all six Berlin sewage plants with ozone or similar techniques would cost $584 million. Estimates of equipping 600 similarly large wastewater plants in Germany with quaternary treatment technology range from $10.6 billion to $47 billion. Kraus’ response was unequivocal: “It’s important that we as a city make sure our water is purified using the best available technology, but there’s no doubt who has to pay for it — the industries that cause the pollution.”

Industry, as might be expected, sees it differently. Lobbyists for pharmaceutical and cosmetics companies are pressuring the European Commission to soften — or even scrap — the legislation, which mandates that those sectors cover 80 percent of the construction and operating costs of quaternary treatment. Under the revised Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive, every treatment plant serving more than 150,000 people must be retrofitted by 2045. Smaller plants must also be upgraded if they are located in areas where micropollutants pose a risk to drinking water supplies.

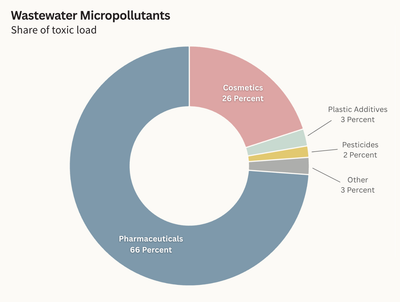

The exact share of costs a company must bear, according to the directive, depends on the quantity of environmentally problematic ingredients it produces and how toxic they are for aquatic organisms. The E.U. Commission has based its findings on an evaluation of scientific studies that found that the pharmaceutical and cosmetics industries are responsible for 66 percent and 26 percent, respectively, of toxicity in urban wastewater.

Industry trade groups are seeking to capitalize on waning enthusiasm for progressive environmental policies.

Initially, pharmaceutical and cosmetics industries said they supported the directive’s overall objectives. But they noted, in a joint statement, that the “arbitrary decision to pick only two sectors, human pharmaceuticals and cosmetics, to pay for the pollution caused by others fails to incentivize greener product development [by] all polluters.”

Since the directive went into force, those industries have pushed back harder. Trade groups are casting doubt on the scientific studies underpinning the new sewage regulations. They are lobbying to cut red tape in environmental policy and seeking to capitalize on waning enthusiasm for progressive environmental policies. Amid active and looming wars in and around Europe, sluggish economic growth, punitive tariffs imposed by the U.S., and aggressive anti-environment rhetoric from right-wing populist parties, many politicians and E.U. Commission strategists are distancing themselves from previous commitments enshrined in 2020 in the landmark European Green Deal — a policy package with carbon dioxide reduction, biodiversity protection, and the phaseout of harmful substances as core priorities.

Between March and July, pharmaceutical and cosmetics trade groups and companies took their case to the European Court of Justice. More than a dozen complaints were filed, with plaintiffs calling either for broader inclusion of other sectors, like the food industry, in the payment mechanism; for the removal of the “polluter pays” requirement; or even for voiding the entire Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive.

Source: European Commission.

Yale Environment 360

Manufacturers of generic drugs feel particularly threatened. For the diabetes drug metformin, for example, production costs could increase by a factor of 4.5, warns Josip Mestrovic, managing director of Pro Generika, a trade association. “If this really happens and nothing changes, we will have to take metformin off the market,” he says.

According to the German Federal Environment Agency, the active ingredient in metformin can have hormone-like effects on aquatic organisms. In experiments with fish, it triggered sex changes from male to female and inhibited the growth of larvae.

“The European Commission should stop the implementation of the directive and dare to start afresh,” says Jörg Wieczorek, CEO of the industry association Pharma Deutschland. The VKE cosmetics association — which includes companies such as Chanel and L’Oréal — seeks to at least cap the industry’s share of the costs at 1 percent. Lobbying groups are calling for a model in which water consumers contribute to the cost of advanced treatment. They point to Switzerland, where the cost for upgrading sewage plants is shouldered by water consumers through a levy of $11 per capita through water bills, not by polluters themselves.

Experts are calling for doctors to learn more about the environmental risks of pharmaceuticals they give to patients.

Water utilities and environmental economists argue against that. “The cost of removing micropollutants should not fall upon water users like private households and small local businesses but on those who are causing the problem,” says Oliver Loebel, secretary general of EurEau, a Brussels-based organization that represents 38 national associations of drinking water and wastewater operators across Europe. He argues that the Swiss model doesn’t provide any incentive for manufacturers to reduce micropollutants and replace substances that harm aquatic life.

Loebel hopes the impact of the new urban wastewater directive will go beyond simply cleaning up pollution after the fact. He sees the legislation as a potential driver for industry to replace environmentally harmful substances with safer alternatives. “The pharmaceutical industry prides itself on its ability to develop new substances, so it should be possible to avoid further environmental harm” and market alternative substances that can be removed more easily or that break down into harmless molecules, he says. A less harmful alternative to diclofenac, for example, already exists, says Loebel.

“The pharmaceutical and cosmetics industries have plenty of time to adapt — and a straightforward way to reduce costs by cutting pollution through innovation over the coming years and decades,” Loebel says. A clause in the directive requires regular reviews to assess whether access to medicines is being affected, and whether other sectors, like the food industry, should be included in the cost-sharing mechanism.

Scientists take samples from the Elbe River in Germany as part of a study on pollution in European waterways.

André Künzelmann / UFZ

Many experts are calling for doctors and pharmacists to learn more about the environmental risks of pharmaceuticals they give to patients. In the Stockholm region, an expert panel has developed what’s known as the Wise List, a set of prescribing recommendations that prominently includes such information. The idea is that doctors will prescribe the least environmentally harmful substance.

But without improved water treatment, the problems will only get worse. Erik Gawel, chief economist at the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research in Leipzig, warns against delaying investment in quaternary treatment: “The longer we wait, the harder the chemization of our lives will catch up with us later, when micropollutants gradually find their way into groundwater and drinking water,” he says.

In August, the powerful E.U. Commission promised to conduct and publish a new study about the costs of quaternary treatment as well as the potential impacts on concerned sectors, based on “the most recent and relevant data.”

“For the time being, I see no appetite in the E.U. Commission to reopen the directive,” Loebel says. But if that should happen, he warns, there’s a danger that “the directive would basically collapse…. Even if fewer politicians are pro-environment these days, they should at least be pro-water.”