The Korean government’s COVID-19 vaccine policy has undergone several changes: First, during the COVID-19 outbreak, the policy agenda focused on quarantine and domestic vaccine development until the first half of 2020. During this period, the Korean government criticized vaccine nationalism in high-income countries and adhered to its plan to procure vaccines through COVAX. However, since the average number of newly confirmed patients per day increased significantly from November 2020 onward, the government faced criticism for the failure of its quarantine policy. In addition, the Moon administration encountered widespread criticism for the government’s failure to secure vaccines, the problem of prosecution reform, and the failure of real estate policy [67]. Second, under pressure to secure vaccines, the government followed a two-track strategy of securing overseas vaccine supplies and supporting fast-paced domestic vaccine development [23, 34]. Third, on May 21, 2021, during the Korea–US summit, the KORUS Global Vaccine Partnership introduced some changes in vaccine procurement. The Moon administration considered this meeting and partnership an opportunity to commence the Global Vaccine Hub initiative, which aimed to make Korea a global vaccine supply center by ensuring the contract manufacturing of vaccines and advancement of vaccine technology through technology transfer or domestic development ([81], 440). Since then, the government has consistently stated that it will ‘mobilize all possible administrative power and financial resources’ for the GVHP using ‘all-out war’ metaphors, such as ‘with full force’ [81]. In this context, we identified a total of four governmental techniques in the GVHP.

Rationalization by calculative practice: money and ranking as criteria

According to the Korean government, the GVHP plans ‘to develop and commercialize the first domestic [Korean] COVID-19 vaccine in the first half of 2022 and invest 2.2 trillion Korean won over five years to enter the top five in the world’s vaccine market by 2026’ [17]. GVHP aims for Korea to become a top-tier supplier in the global vaccine market without addressing unequal global vaccine distribution. Accordingly, GVHP is not only an industrial strategy in the biopharmaceutical sector but also a national management strategy to increase Korea’s global ranking through performance improvement [44]. The country’s image and competitiveness in the international community are represented using numbers [38].

Further, GVHP’s goal, period, and invested amount are all presented in numbers, which enabled the measurement and standardization of the project’s performance. The budget invested in GVHP was larger than that invested in Nuriho for 12 years, Korea’s first purely domestic rocket launched in 2022, showing its priority.

Calculative practice limits the global inequality in vaccine access to economic and technical issues. High-income countries, including Korea, make national profits by selling vaccine products, while seeking to fulfill moral obligations for external legitimacy. One way to show global responsibility without damaging national interests is through donations. The Korean government donated ‘$200 million to COVAX’ [52] in 2021, ‘an additional $300 million to ACT-A’ [86], and ‘$15 million to ACT-A SFF’ [81]. Such donations erase the political and structural context of global inequality in vaccine access, replace actions for health with the amounts spent, and help dismiss the lack of vaccine access in low- and middle-income countries.

Therefore, even in global health crises, governments adopt calculative practices to preserve their national interests. Using numbers prevents the involvement of personal, social, and historical contexts of the ones producing and using them [46]. Vaccines are treated as commodities, the global space is considered a hierarchical market, and the state is an atomistic entity that competes with other countries for ranking. Furthermore, the equitable global vaccine distribution issue became a problem that can be solved economically and technologically, which depoliticizes causes and alternatives. Paradoxically, this strategy, i.e., numero-politics or politics of numbers, forces actors to focus their interests and efforts on goals quantified in a particular political way ([48], 261–263).

Business-centered system and policy

Countries’ use of calculative practice is often accompanied by their use of certain forms of power and decision-making structures ([49], 84–85), particularly in a business-friendly manner.

The shift from the Korean government’s COVID-19 vaccine policy to GVHP highlighted private companies’ leading role. The transition was spurred by the 2021 Korea–US summit. The summit’s main agenda was the Big Deal, in which Korea invested in the United States’ industry in return for vaccines. Executives of the Samsung, SK, and LG groups accompanied President Moon on his US tour as economic delegates, and the countries concluded a big deal at this summit. Major Korean companies established a plan to invest 44 trillion Korean won, approximately 33.3 billion US dollars, in important US sectors such as semiconductors, batteries, and automobiles, and President Biden publicly expressed gratitude to these Korean entrepreneurs [37]. In return, the United States provided Janssen vaccines to Korea under the name ‘US–Korea military alliance’, even though the former faced significant opposition since Korea was a high-income country with relatively ample vaccine stocks and stable COVID-19 spread [87].

Further, the two leaders stated that they had ‘agreed to establish a comprehensive global partnership for vaccines combining the US’s advanced technology and Korea’s production capacity’. Accordingly, four MOUs were signed between Novavax/Moderna and the Korean government/companies [74]. The cooperation of large corporations as quasi-diplomats was a vital requirement for the Korean government to lay GVHP’s foundation, and these corporations’ influence on vaccine policies expanded gradually over the years.

The government committee responsible for designing and implementing the project was largely shaped by a pro-business orientation. Two aspects of GVHP reveal its business-centered nature: First, its committee composition was biased. The working committee consisted of 13 members, each from the government and private sector. The private sector comprises nine experts from seven different sectors, one representative from related organizations, and three representatives from associations [9]. All three associations and nine experts are from or closely related to the biopharmaceutical industries. The decision-making process, conducted solely by bureaucrats and experts in a closed space, involves the technicalization and depoliticization of vaccine-related discussions and hampering other political actors from being engaged. As a result, despite civil society organizations’ demands for support of the TRIPS waiver, the committee focused only on vaccine development, production, and exports by Korean companies.

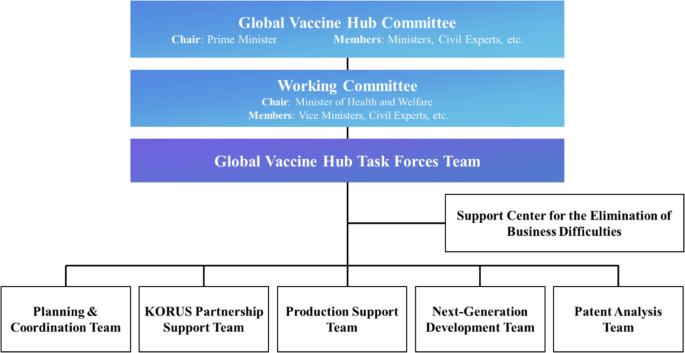

Second, the implementation system and policy contents of the Global Vaccine Hub Committee (GVHC) are designed to support private companies’ profit-seeking efforts (Fig. 1). The role of a center and five teams under the Global Vaccine Hub Task Forces Team includes supporting international cooperation between Korean and US companies, facilitating global vaccine and raw material import/export, developing national domestic vaccine strategies, and discussing patent rights. The GVHC was designed to reflect on, support, and benefit domestic companies.

Global Vaccine Hub Committee organization chart. (Source: [18])

In Korea, the tendency of high-value-added industries to foster strategy by governments is not new; rather, it has been pursued continuously since the 1990 s, and the pandemic further accelerated this effort. Further, the Moon administration has supported and ensured the deregulation of the biopharmaceutical industry even before the COVID-19 pandemic [2].

In summary, GVHP exercised governmental power to reinforce corporate support, which generalized the form of business within society and constituted the society’s legal, institutional, and cultural conditions based on competitive principles [11, 64]. Therefore, GVHP is a uniquely Korean expression of global neoliberal governmentality.

Dual strategy: protecting and circumventing patents

The Korean government announced its decision to support domestic companies to ‘create strong patents’ for COVID-19-related technologies/products while strategically circumventing patents overseas [54]. The government implemented various policies to protect the patents of domestic technologies. In July 2020, a joint declaration by the heads of the world’s five major intellectual property offices – Korea, the United States, Japan, China, and Europe – reaffirmed the ‘importance of intellectual property protection’ to support research and innovation in various industries to end COVID-19 as well as economic recovery and job creation in times of crisis [42]. Later, in 2022, the Korean Intellectual Property Office proposed expanding the examinations of national core technologies, including vaccines, and enhancing patent protection by strengthening the quasi-judicial status of patent trials.

The government also promoted domestic companies’ profit pursuit by implementing strategies to avoid patent barriers. As Korea was a late entrant to the global mRNA vaccine market, patent avoidance was needed when companies sought opportunities to maximize profits by circumventing patents. The press release for GVHP included information on overseas patent analysis, avoidance strategies for mRNA vaccine development, and relevant support for Korea’s core technology development [17]). In addition, the government actively considered the possibility of technology transfer, which would benefit domestic development and production. This dual attitude is evident in the Korean government’s Multi-tech Technology Transfer Hub proposal to the WHO in the early days of COVID-19. The proposal was expected to enable technology transfers and investments in the Korean production facilities of various vaccines, including mRNA ([81], 416–417).

With the expectation to develop and commercialize domestic vaccines, the Korean government pursued a dual strategy to circumvent existing foreign patents and protect the (potential) patents and profits of domestic companies. Further, the government guarantees the domestic companies’ monopoly of intellectual property, considering their profits to be national interests and as an indication of the nation’s superiority in global market competition.

Korean and global civil societies strongly advocated waiving the application of TRIPS for COVID-19-related technologies and expanding production to resolve vaccine inequity. Many of these groups expressed solidarity by affiliating themselves with the People’s Health Movement (PHM), a global network of local grassroots health justice activists and organizations. It operates at global, regional, and national branches, including PHM Korea, where several Korean civil organizations with a history of advocating health rights and justice have joined. Korean civil society organizations urged the government and domestic companies to support global initiatives, such as the TRIPS waiver and the COVID-19 Technology Access Pool (C-TAP), to ensure globally equitable access to essential COVID-19 technologies. One of their most prominent actions was calling on both the government and Celltrion to join patent pools like C-TAP, advocating that publicly funded COVID-19 treatments be made available worldwide [39]. This advocacy prompted Celltrion to adjust its stance, such as lowering the price of its treatment in Korea, though it did not share its patents or try to ensure access to the treatment in low- and middle-income countries [39]. Civil groups also recommended invoking compulsory licensing for COVID-19 treatments and vaccines, whether to meet domestic needs or to export doses to countries with limited access [60]. However, these demands were not heeded by the Korean government; instead, it questioned the feasibility of the TRIPS waiver and refrained from announcing any official position, making its implementation impossible. Furthermore, the government clarified that ‘to solve vaccine inequality, production must be expanded, and for this, Korea’s GVHP is needed’ [77], taking over and appropriating the radical demands of civil society in a profit-seeking manner.

In May 2021, the government held a public–private meeting after announcing that it would ‘discuss the measures with the industry’ regarding the TRIPS waiver. In this meeting, companies requested the government to continue supporting vaccine and treatment development, securing raw materials, and strengthening licensing cooperation instead of implementing the TRIPS waiver [77]. Based on the biopharmaceutical industry’s stance, the government opposed the TRIPS waiver in effect, arguing that intellectual property would serve national interest. Simultaneously, it suggested technology transfer or licensing from other high-income countries, including the United States, as the best alternative, given the pandemic as the new growth opportunity.

The government’s dual strategy highlights the uniqueness of Korea’s semi-peripheral position. It is different not only from the attempts of the United States to overcome weakening global competitiveness in the manufacturing industry by strengthening intellectual property rights but also from the efforts of other high-income countries to strengthen intellectual property rights to evade emerging countries’ pursuit. Korea, which has production capacity but lacks source technology, attempts to protect the potential intellectual property rights of COVID-19 treatments or vaccines developed by domestic companies (Celltrion and SK Bioscience), promote technology transfer and contract manufacturing, and circumvent infringement of intellectual property owned by foreign companies (Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna).

Korea presents itself as a global vaccine production hub based on licensing and/or contract manufacturing. Its opposition to the TRIPS waiver and nonparticipation in the C-TAP prevents vaccine production by low- and middle-income countries, which require shared technology and knowledge. In other words, the government’s vaccine policy that was put forward to solve global inequity was just an attempt to maximize Korea’s national interests. As a contract manufacturing base, Korea has only acted as an agent for high-income countries and transnational corporations. For example, two of Korea’s top five vaccine export destinations in 2021 were high-income countries – Australia and the Netherlands [41]. The dual patent strategy embodies governmental rationality, which Korea, as a neoliberal developmental state, exerts by considering the global value chain.

Vaccine diplomacy

The Korean government intends to engage in global pandemic governance and has donated money and vaccines ([81], 411–417). However, these activities are fraught with contradictions. After the Korean government promised financial support to COVAX and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), these institutions substantially supported for-profit Korean companies. For example, the Korean government promised to donate $9 million to CEPI over three years (2020–2022), whereas CEPI decided to provide $2.1 million to SK Bioscience, a Korean company that develops a COVID-19 vaccine ([81], 414). The Korean government mainly considers the COVID-19 vaccine issue to be a matter of diplomacy and business ‘to strengthen global production cooperation’ [17] and ‘to establish Korea’s status as a global vaccine hub country by expanding the international cooperation network’ [75].

According to the Moon administration’s self-evaluation, it had been ‘expanding the international cooperation network’ [81]. However, this did not refer to global solidarity, but to bilateral cooperation that differed by geopolitical and economic position. First, the Korean government signed a cooperation agreement for raw material supply, contract manufacturing, and research and development exchanges with leading countries, such as the United States, European Union, and United Kingdom ([81], 409–410). Korea publicizes its cooperation with these high-income countries due to its pride in becoming an advanced country and the expectation that it will learn advanced technology. Second, the governments of Korea and Australia, countries with similar levels of vaccine technology and gross domestic products (GDP), agreed to cooperate as equals in mRNA vaccine development and clinical trials. Lastly, Vietnam was the only low- and middle-income country with which Korea partnered. The Korean government promised to support establishing a disease prevention and management system in Vietnam based on Korea’s health administration model and secured Vietnam as an overseas site for vaccine clinical trials ([81], 411). Korea’s attitude toward foreign countries with different economic and technological levels reveals its linear and hierarchical global perceptions [3].

Moreover, the Korean government sought not only to establish a partnership with the US, the hegemonic country, but also to align itself with the broader contours of US global strategy. The Korea–US vaccine alliance helped strengthen the countries’ military alliance, as follows: (A) In March 2021, two months before the Korea–US summit, the Special Measures Agreement, which had been one of the biggest issues troubling the Korea–US military, was concluded [13]. (B) At the summit, Korea clarified that it would side with the United States in all cases where the latter conflicted with China, such as the case of the Mekong region [78]. (C) The United States sent the Janssen vaccine to Korea to benefit soldiers and workers under the Korea–US military alliance [73]. (D) The summit lifted the Korea–US missile guidelines to establish containment against China [4]. As indicated by these events, military alliances aimed at furthering hegemonic competition were openly strengthened during the pandemic.

The COVID-19 vaccine distribution issue further strengthened the US’s intention to increase containment against China and enhance the Indo–Pacific strategy, while providing Korea an opportunity to pursue its political and economic interests. Based on the agreement to link Korea’s New Southern Policy with the US Indo-Pacific Initiative, the two countries discussed ways to cooperate in the this region, such as supplying vaccines and essential medical supplies and exchanging experts [76]

Strengthening the Korea–US military and security alliance under the pretext of vaccine production has significantly contributed to US global hegemony and enhanced Korea’s involvement in this strategy. The Korea–US joint statement reveals that the security competition has expanded beyond the military dimension to include the health security mechanism.