Narrative review

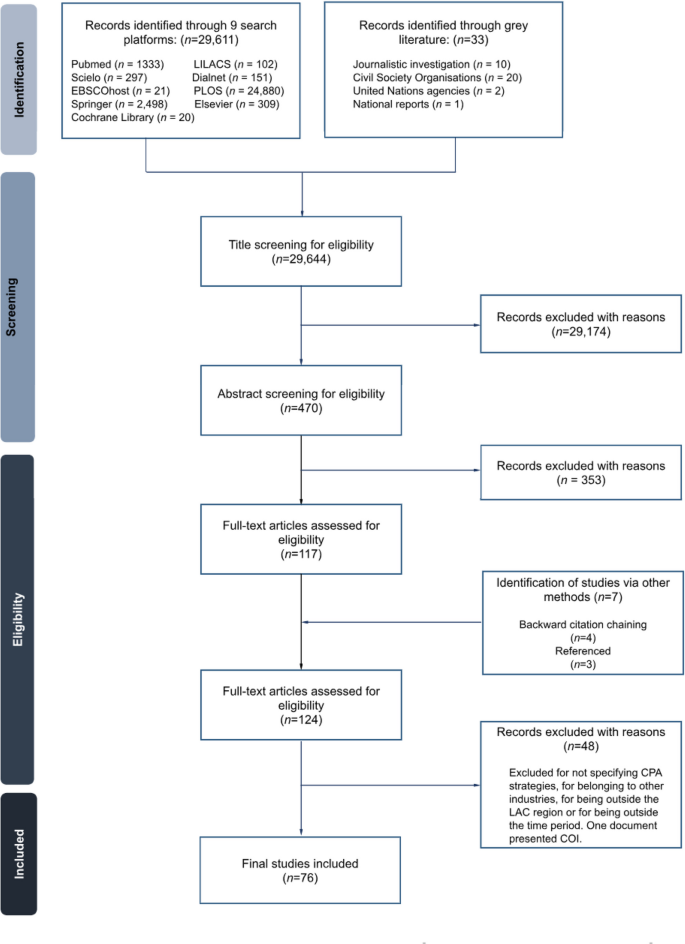

The search provided an initial screening sample of 29,644 documents from search platforms (n = 29,611) and grey literature (n = 39). Following a title screening, 29,174 documents were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria (Table 1). For example, documents dated outside the specified time period or including non-LAC countries were excluded. Among the 470 abstracts screened for eligibility, 353 were excluded for various reasons (e.g., documents with CPA strategies from other industries, documents without specified CPA strategies, documents with conflict of interest (COI), among others). As a result, 124 full-text documents were assessed, considering seven documents included by backwards citation chaining or by researchers’recommendation. Finally, 76 documents were included in the analysis, representing a range of different approaches (Fig. 1). The majority were scientific studies (n = 45), followed by reports (n = 18), investigative journalism reports (n = 9), and institutional reports (n = 4). The complete list of documents included in the narrative review is available in Additional File 3.

Flow diagram of document review on Food Industry CPA in Latin America and the Caribbean

Among the 76 documents, 56 correspond to documents from a specific country, and 20 correspond to multi-country documents. In general, 24 countries were identified, 15 of which were from Latin America (Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru and Uruguay) and nine from the Caribbean (Barbados, Bahamas, Belize, Bermuda, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Grenada, Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago). Importantly, all the documents involving a Caribbean country or a specific country in Central America (Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Panama) were multi-country studies (n = 4, 5.3% and n = 6, 7.9%, respectively). The countries with the most significant number of documents identified in this review were Mexico (n = 22, 28.9%) and Brazil (n = 12, 15.8%). Figure 2 shows a heatmap with the number of documents included for each country in the LAC region.

Latin American and Caribbean countries with evidence of food industry CPA from 2018 to 2024. No evidence (grey): a country with no evidence; Very Low (light blue): a country with 1–5 documents; Low (sky blue): a country with 6–10 documents; Moderate (azure blue): a country with 11–15 documents; High (cobalt blue): a country with 16–20 documents; and Very High (navy blue): a country with more than 21 documents. Own elaboration

With respect to the year of publication, from 2020 onwards, there was a notable increase in the dissemination of evidence on the CPA of the food industry in public health, food and nutrition public policies. The year with the highest number of published papers was 2022 (n = 18, 23.7%), while the year with the lowest number was 2019 (n = 6, 7.9%).

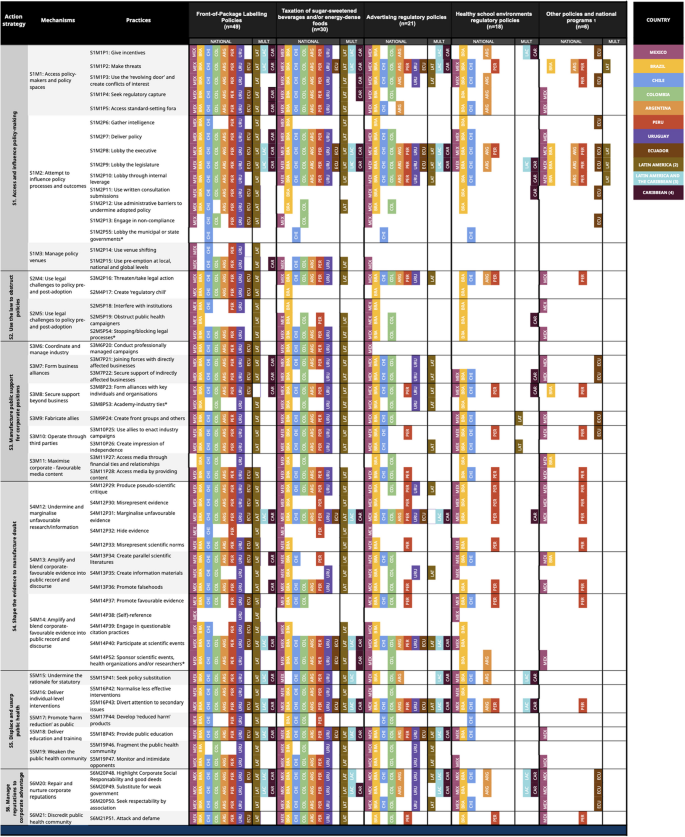

Evidence of action strategies, practices and mechanisms of corporate political activity by health, food and nutrition public policies in Latin America and Caribbean countries

More than half of the documents included in the review described CPA strategies related to the FOPNL policy (n = 49, 64.5%). Conversely, a smaller proportion of documents concerning the taxation of sugar-sweetened beverages and/or energy-dense foods (n = 29, 38.2%), regulation of UPPs advertising (n = 21, 27.6%) and the regulation of healthy school environments (n = 18, 23.7%) were identified. Notably, only one study from Peru documented the regulation of trans fatty acids (1.32%) [30]. A total of ten documents addressed other types of policies, such as interference by large agribusiness corporations (n = 2, 2.6%) and national programmes aimed at reducing malnutrition (n = 2, 2.6%) or sodium intake (n = 1, 1.3%). The rest of the documents did not mention a specific policy (n = 5, 6.6%) (Fig. 3).

Food industry corporate political activity in LAC based on health, food and nutrition policies (2018–2024). *Additional practices included in the taxonomy: 1. Other policies and national programmes include policies to reduce sodium intake, trans fatty acid regulation, food production and national food programmes focused on childhood malnutrition. 2. Countries belonging to”LAC”in the multi-country documents: Argentina, Barbados, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Trinidad and Tobago and Uruguay. 3. Countries belonging to “LAT” in the multi-country documents: Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico, Panamá, Paraguay, Peru and Uruguay. 4. Countries included in the Caribbean documents: Bahamas, Belize, Bermuda, Trinidad and Tobago, Jamaica and Grenada. Own elaboration, adapted from Ulucanlar et al. (2023)

Notably, the practices of making threats (S1M1P2), lobbying the executive (S1M2P8), lobbying the legislature (S1M2P9), marginalising unfavourable evidence (S4M12P31), participating at scientific events (S4M14P40), diverting attention to secondary issues (S5M16P43) and providing public education (S5M18P45) were identified in all subregions and countries’ documents related to FOPNL (Fig. 3).

As previously mentioned, the most widely documented policy across all subregions and countries was related to FOPNL. Mexico has the most extensive evidence of industry interference in this policy, with documented instances of all CPA action practices, except for lobbying municipal or state governments (S1M2P55) and accessing media through financial ties and relationships (S3M11P27) (Fig. 3). For example, in November 2019, Nestlé’s CEO sent a letter urging its suppliers to mobilize against the FOPNL and send letters to the Mexican government officials to “intervene” in the process (S3M7P21) [34].

Concerning the taxation policy on sugar-sweetened beverages and/or energy-dense foods, Brazil was the country with the greatest variety of CPA practices on this policy, documenting all mechanisms, except for managing policy venues (S1M3) and undermining the rationale for statutory policies on corporate practices (S5M15) (Fig. 3). In contrast, Ecuador had the least documentation available on this policy. With respect to healthy school environment policy, Brazil again stands out for documenting a greater number of practices related to this policy identified in the reviewed documents. However, in Colombia, Uruguay and Ecuador, there is no evidence that CPA practices are associated with this policy.

With respect to policies regulating UPPs advertising, Mexico has documented the highest cases of CPA interference by the food industry. However, corporate influence on this policy has also been reported across all subregions and countries. Specifically, documented practices include making threats (S1M1P2), lobbying the executive and legislative (S1M2P8 and S1M2P9), marginalising unfavourable evidence (S4M12P31), participating at scientific events (S4M14P40), diverting attention to secondary issues (S5M16P43) and providing public education (S5M18P45) (Fig. 3). Regarding making threatspractice (S1M1P2), in Peru the Law N° 30,021 (enacted in 2013 and including the regulation of UPPs advertising) generated strong opposition from industry and the media due to the potential economic losses it would cause and led to discussions with members of Congress from various parties to block the proposal [35].

Notably, regarding food production policies (e.g., Federal Law for the Promotion and Protection of Native Corn, General Health Law on Pesticides, among others), Mexico is the only country with documented CPAs in this area, and all six strategies have been identified. In contrast, for national programmes aimed at preventing malnutrition or reducing sodium consumption, CPA practices have been documented in Argentina, Ecuador, Brazil, Costa Rica, Paraguay and Peru, primarily through the strategies of accessing and influencing policymaking (S1) and manufacturing public support for corporate positions (S3) (Fig. 3).

In terms of health, food and nutrition public policies based on the policy cycle, the policy adoption phase (Phase 3) was the most thoroughly documented phase in the FOPNL and the regulation of UPPs advertising. Conversely, in the taxation of sugar-sweetened beverage and/or energy-dense food policies, the regulation of healthy school environments, national programmes and food production policies, the policy implementation phase (Phase 4) was the most prevalent. Less evidence was identified for the monitoring and evaluation phase (Phase 5), with only five documents: two on FOPNL, two on the taxation of sugar-sweetened beverages and/or energy-dense food policy and one on the regulation of UPPs advertising policy. Figure 3 presents a comprehensive overview of health, food and nutrition public policies by LAC country, categorised according to action strategies, mechanisms and practices (ASMP) of CPA.

Evidence of CPA strategies, practices and mechanisms of corporate political activity by country in the Latin America and Caribbean and policy cycle

Regarding the CPA of the food industry in the five phases of the policy cycle, it was determined that there is a greater volume of evidence in the phases of policy adoption (Phase 3: n = 32, 42.1%), policy formulation (Phase 2: n = 27, 35.5%) and policy implementation (Phase 4: n = 25, 32.9%) of public health, food and nutrition public policies. For example, all four documents from the Caribbean evidenced the CPA of the food industry in the policy adoption phase (Phase 2). In contrast, less evidence was identified for the agenda-setting phase (Phase 1: n = 14, 18.4%) and the monitoring and evaluation phase (Phase 5: n = 3, 3.9%). The three documents identified in the monitoring and evaluation phase (Phase 5) belonged to Mexico, Uruguay and Brazil. Eleven documents (14.5%) did not refer to a particular policy cycle phase or consider exclusively on one type of CPA strategy.

In terms of CPA action strategies in LAC countries, accessing and influencing policy making (S1) was the most frequently identified strategy in the documents included in this review (n = 69, 90.7%), especially in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru, Uruguay and the Caribbean (Table 2). However, despite the consensus on the action strategy, the most frequently reported mechanisms and practices differ across subregions and countries. In Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and Peru, the most reported mechanism was attempting to influence policy processes and outcomes (S1M2) through the practices of lobbying the executive (S1M2P8) and lobbying the legislature (S1M2P9). For example, throughout the process of approving and regulating the Law for the Promotion of Healthy Eating for Children and Adolescents in Peru, it was necessary to face opposition from interest groups and lobbies linked to the industry sector, which sought to influence discussions and decision-making in the executive and legislative branches and which also operated at the level of the media and through civil organisations [36].

In contrast, in Mexico, Argentina, Ecuador and Uruguay, the food industry gained access to and influenced policymaking by accessing policymakers and policy spaces (S1M1) through practices such as making threats (S1M1P2). For example, to intimidate legislators in Uruguay, food industry representatives stated that the FOPNL regulations would lead to job losses and price increases due to reduced sales and higher costs [106]. Additionally, the practice of using the revolving door and creating conflict of interest (S1M1P3) was evident in Mexico, where Patricio Caso, the government official responsible for the controversial Guideline Daily Amount (GDA) labelling promoted by the food industry, is now working as a senior manager at Coca-Cola Mexico [94]. These examples highlight how these two practices are employed to access and influence policymaking in LACs.

Although the mechanism of managing policy venues (S1M3) was not the most common (n = 9, 9.2%), the practice of using the pre-emption at local, national and global levels (S1M3P15) was documented, primarily in Latin America (LATAM). An example of this can be seen in countries such as Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay, where the food industry used the Mercosur (a regional trade bloc in South America) as a convenient excuse to delay discussions on FOPNL, arguing the need to”harmonise”labelling standards at the regional level [39]. Finally, one study documented an example of the practice of using venue shifting (S1M3P14), which occurs when corporate actors ensure legislation occurs in regulatory jurisdictions more favourable to them. This practice was reported in Peru, where there was a clear contrast between the space granted to the food industry and the opportunities provided to advocates during the discussions on the initiative for the Law of Promotion of Healthy Eating for Children and Adolescents [45].

The second most evidenced strategy was manufacturing public support for corporate positions (S3), with 56 documents (73.7%), primarily in Brazil, the Caribbean, Chile, Ecuador and Mexico. The mechanisms commonly employed were forming business alliances (S3M7), securing support beyond business (S3M8), fabricating allies (S3M9) and working through third parties (S3M10). Among these mechanisms, the one related to securing support was one of the most thoroughly documented, mainly through the practice of forming alliances with key individuals and organisations (S3M8P23). Brazil serves as a notable example, where the food industry partnered with universities and research institutes to create a platform called “Processed Foods”, which aimed to “offer a more comprehensive view of the food and beverage industry, in contrast to a vast amount of myths and prejudice that have been spread”. [69] This example illustrates how the food industry successfully secured the support of experts and scientific groups in various contexts, ensuring ownership and control over its allies.

Importantly, the practice of creating front groups and others (S3M9P24) was one of the most common within the strategy related to manufacturing public support for corporate positions (S3: n = 27, 35.5%), especially in Mexico (n = 15, 55.6%). In this country, the case of the Mexican Observatory on Non-communicable Diseases(OMENT in Spanish) stands out. The OMENT was a Nestlé-funded research organisation that monitored obesity and diabetes, including the effects of the sugar-sweetened beverage tax, with representatives from the food and beverage industry on its Advisory Council [83].

The strategies corresponding to shaping the evidence to manufacture doubt (S4), displacing and usurping public health (S5) and managing reputations to corporate advantage (S6) were the least documented. However, the mechanisms of undermining and marginalising unfavourable research/information (S4M12) and producing or sponsoring favourable research/information (S4M13) were identified in more than half of the documents included in the review (n = 40, 52.6%) through the practices of misrepresenting evidence (S4M12P30) and creating parallel scientific literatures (S4M13P34). For example, in Mexico, the National Association of Soft Drink and Carbonated Water Producers(ANPRAC in Spanish) paid approximately 93 thousand dollars to the College of Mexico to carry out a study on the taxation of sugar-sweetened beverages that Mexico implemented in 2014. The contract included terms that granted the ANPRAC the right to supervise and review the research progress [95].

Finally, the strategy of using the law to obstruct policies (S2) was mainly documented with the practice of threatening/taking legal action (S2M4P16: n = 28, 36.9%). In Chile, the National Advertisers Association (NAA), whose membership list includes multinational food industry companies such as Coca-Cola, Unilever and Nestlé, emphasises that the restrictions contained in the Food Act bill would violate Article 19 of the Chilean Constitution, which protects the freedom to express opinions and to inform, without previous censorship, in any form and by any means [72].

In summary, more than 900 examples of CPA practices were documented throughout the review. All practices were identified at least twice across the entire set of documents, although not necessarily in every document. Table 2 shows the key results by country, highlighting the most prominent policy phase identified, along with the main CPA strategies, mechanisms and practices reported by the food industry, accompanied by illustrative examples.

New practices found in the documents included in the review

No new strategies or mechanisms were introduced; however, four additional practices were included: sponsoring scientific events, health organisations and/or researchers (S4M14P52); academic capture through direct contract (S3M8P53); blocking/obstructing legal processes (S2M5P54); and lobbying municipal or state government (S1M2P55). The detailed definitions of these new practices can be found in Additional File 2.

The most frequently reported new practice was sponsoring scientific events, health organisations and/or researchers(S4M14P52: n = 14, 18.4%), enabling the food industry to position its priorities on the public health and education agenda, particularly in Mexico, Colombia, Argentina and Chile. This is illustrated by cases such as Nestlé, which, since 2005, has funded a nutritional research prize in partnership with the Chilean Nutrition Society [73]; or Panama, where the food industry has also provided scholarships and awards for primary, secondary and university schools through the Castillo Foundation, which is linked to the beverage industry [40].

The other three new practices were found in minor proportions. The practice of blocking/obstructing legal processes (S2M5P54) was identified in Mexico, Brazil, Colombia, and LATAM more broadly. The following are two illustrative examples drawn from different countries. In early 2020, Mexico’s food industry chambers of commerce successfully filed a motion to suspend FOPNL regulation, declaring themselves “forced to take legal action”, thereby paralysing its publication. However, the suspension was subsequently revoked, prompting a substantial increase in appeals from food industry companies and prestigious law firms, orchestrating an enormous legal force against the FOPNL [94]. In Chile, Pepsico, Carozzi and Kellogg’s took the Chilean Treasury to court, arguing that products such as Cheetos and Gatolate could not be banned because they were not advertisements for children but rather elements that constituted the identity of the brands [45].

The practice of academic capture through direct contract(S3M8P53) was identified in Brazil, Colombia and LATAM (n = 4, 5.3%), as demonstrated in Colombia, where the board members of the International Life Science Institute (-ILSI- a front group of the food industry to influence health policies) included a retired professor from the National University of Colombia and the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana [77].

Finally, the practice of lobbying the municipal or state government(S1M2P55) was evidenced only in Chile (n = 1, 1.3%) but several times. In this country, the municipal or local authorities were frequently lobbied, particularly in locations where the food industry companies had factories or distribution centres [74].