Like many Americans, I may only be one generation away from birthright citizenship—a concept that defined this country’s promise for so many immigrants.

The complaint about us poets is that we make everything too complicated. When the world needs something like a simple protest song or something patriotic, we mutter vaguely about different ways to look at a thing.

Immigration, for example. Is it fundamentally the same today as it was for my grandparents, or completely different? Or if somewhere in between, then where, exactly?

If certainty about that question is the test, then I fail.

My grandfather Morris Eisenberg immigrated to the United States in 1908 as part of the Galveston Plan, a charitable project supported by prosperous German Jewish and long-established Sephardic families in New York. Those Schiffs and Cardozos—or whoever they were—wanted to do something for their Eastern European brothers and sisters, who in the new 20th century were coming to New York in droves: too many of them, stirring sympathy, but also embarrassment. Their names, their language, their manners, their looks, their clothes, their very smells were alien, peculiar, not American. How to help them, without the city of New York being overrun by them?

There was a rabbi in Texas who said that his congregation there could use more Jews, plenty of them, so the Galveston Plan provided ships such as the Frankfort, which sailed from Bremen to Galveston, with teenager Morris Eisenberg aboard, arriving on June 15, 1908. He settled in Little Rock, Arkansas. His firstborn child, my mother, was born there in 1916. When she was in high school, the family moved to Long Branch, New Jersey, where my grandparents lived down the street from me—four doors away—all through my childhood and my years in high school and at Rutgers. I knew my Zaydee Morris well, beyond question. For years, I saw him every day.

On an official “Registration Card” (apparently related to the military draft as well as citizenship) dated June 5, 1917, in Conway, Arkansas, Morris’s age is listed as 26. Line 10 of that card records his marital state as “Married” and his race as “Caucasian.” The card includes, on line 4 the following question:

Are you (1) a natural born citizen (2) a naturalized citizen (3) an alien (4) or have you declared your intention (specify which)?

Current Issue

In response, Morris—or the Arkansas official who was filling in the form—wrote on line 4 the words: “Declared Intention.”

All my life, I have assumed that he became an American citizen some time not long after that 1917 declaration. But recently, I happened to look at another document, with the heading: “United States of America: Declaration of Intention” dated January 24, 1939, in Freehold, New Jersey. This time, 22 years later, the entry for Morris Eisenberg’s race is “Hebrew.” And in 1939—the year before I was born, and not long before my grandfather’s son, my uncle Julian Eisenberg would enter the United States Army—Morris Eisenberg, now 46 years old, again declares his intention to renounce all fidelity and allegiance to any other state or ruler, and (so I assume!) to become a naturalized American citizen.

I can no longer presume that Morris Nachman Eisenberg ever actually became a citizen. His wife, my Nana, was born in Brooklyn. It’s possible that my grandfather did complete the naturalization process some time before I was born, or when Julian entered the army. Julian, my Uncle Julie, fought in and survived the Battle of the Bulge. What feels most likely about the question of legal status as an immigrant is that my grandfather never got around to it.

So there is the ambiguity. Like unknown numbers of Hispanic and Asian and Brazilian and Irish and West Indian people in various circumstances, times, and places, Morris the Hebrew Caucasian immigrant (his official color in 1939 was “white” and his complexion “dark”) apparently did not consider his legal status to be an urgent matter. An ancient, two-pronged strategy for survival may apply here: Follow the rules. Avoid official procedures.

Did he rely confidently on the American principle of “due process”? Maybe not with those two words, but yes, absolutely, my grandfather lived with certainty that in this country, if you obey the laws and behave decently, you will be protected. Absolutely, he loved the United States of America. Whether he was ever naturalized or not, he was what I would call patriotic, beyond a doubt.

Legally, Morris Eisenberg may or may not have been a citizen of the United States. Morally and practically, in his soul, he was a citizen. He and Nana, as proud and concerned parents of a GI (that old-fashioned term) gave a lot of energy, practical and emotional, to the USO. (The three letters, which meant so much in my wartime early childhood, stand for the United Service Organizations, which provided local support and entertainment to members of the armed services. My grandmother cooked every week for the USO parties for servicemen on Third Avenue in Long Branch.)

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

In my own occupational hazard, in the obsessive habits of my chosen art, I find myself quibbling with the peculiarities of the word: “natural-ized.” The two halves are nearly opposite in meaning. For me, a meaningful contradiction. But in terms of political arguments or editorials, perhaps not the main point. In a new, personal quantum of meaning, I may well be only one generation removed from birthright citizenship.

I treasure a photo of my grandfather as a young man in Little Rock, where he is sitting on a motorcycle and wearing a necktie. Three different people, seeing the picture, have asked me if he was a Black man. No: pure Ashkenazi, born in a shtetl. Maybe the lighting makes the photo (like too much poetry?) ambiguous? Sometimes, I have let myself think there is something in the facial expression: a jaunty, however daunted, assertion of identity? I don’t know, and I don’t know how significant this family story is, as an example of changing or enduring threads in the fabric of American identity.

More from The Nation

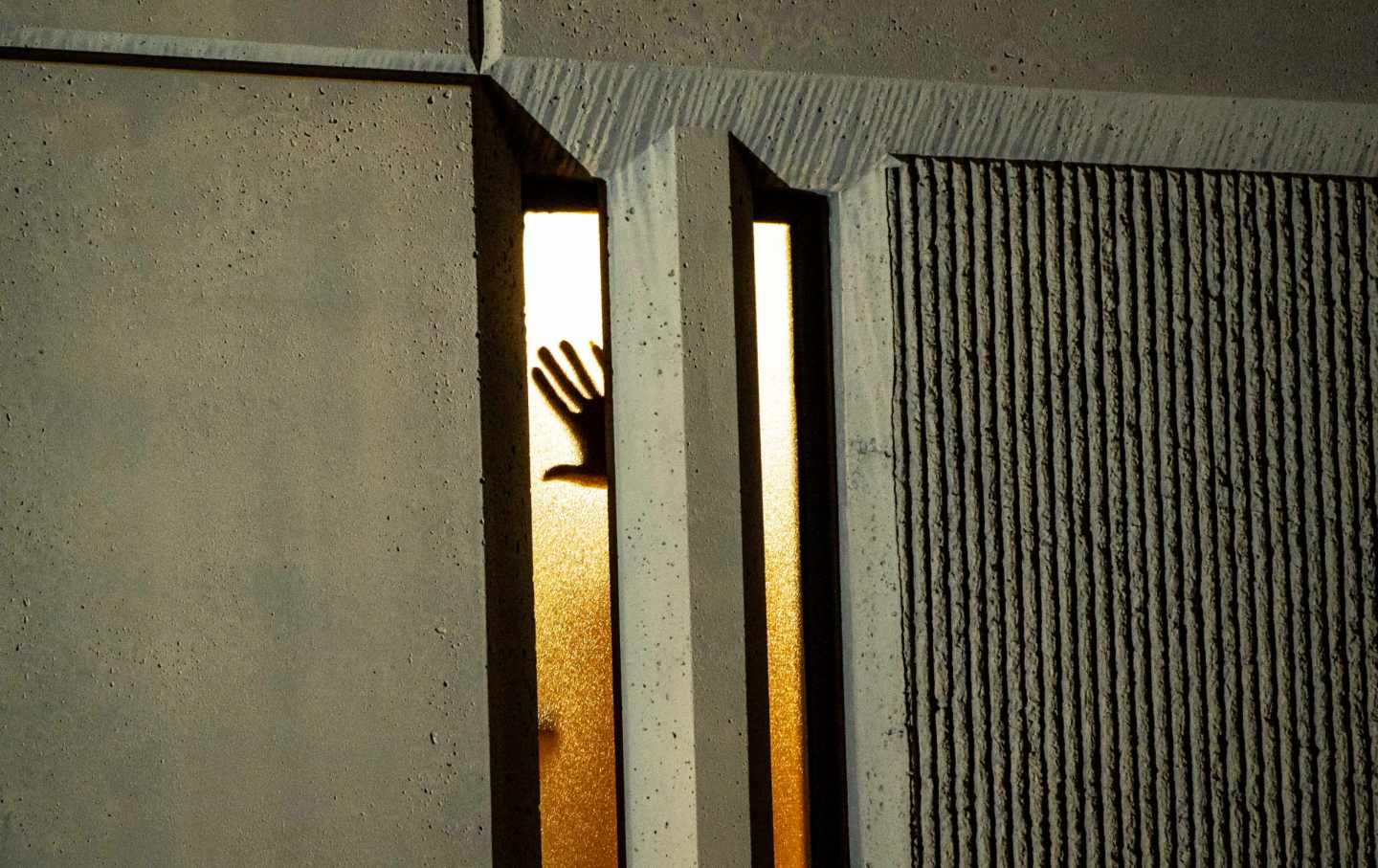

In a Washington county jail, solitary confinement is the worst, most degrading, foulest experience you could ever imagine.

Christopher Blackwell

Rather than deporting millions of migrants, this Republican president opted for the opposite strategy—legalizing them.

Brad Swanson

The administration knows that subduing history as it is doing works to keep people of color in this country disunited and at odds with each other.

Keenan Norris

During a recent trip to Tallinn, I visited the horrific manifestations of an unredeemable totalitarian regime. A similar system is unfolding in Trump’s America.

Sasha Abramsky

The university agreed to a $221 million payout, tacitly conceding spurious right-wing conspiracy theories about higher education.

Chris Lehmann

In the 1980s, the professional wrestler portrayed himself as an all-American hero—but he was really a “jabroni” the entire time.

Obituary

/

Dave Zirin