Analysts say the administration’s policies will lead to $114 billion in offshore wind investments being canceled or delayed.

This has had a devastating effect on offshore wind, especially on the East Coast, where just two years ago some 30 utility-scale wind farm lease areas, spread across the continental shelf waters from Maine to South Carolina, were in the permitting and planning stages of development. According to a July 2024 report by the American Clean Power Association, investment in U.S. offshore wind projects was predicted to hit $65 billion by 2030. By 2050, the report said, the country could be generating 86,000 megawatts of offshore-wind-generated electricity, enough to power roughly 40 million homes.

But in an April report, the market research firm BloombergNEF forecast a 56 percent decrease in offshore wind development by 2035 compared to its prediction the previous year. This reduction will delay or cancel some $114 billion in offshore wind investments, according to the report.

What remains of American offshore wind activity today are just seven farms off the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast coasts. The country’s first wind farm to be finished was a small, five-turbine array off Rhode Island’s Block Island, which became fully operational in 2016. The U.S.’s first utility-scale farm, South Fork, came online just two years ago; it is located off Long Island, New York, and consists of 12 turbines capable of powering up to 70,000 homes.

U.S. wind farms.

Yale Environment 360

The remaining five farms are still under construction. Massachusetts’ Vineyard Wind, located about 15 miles off the coast off Martha’s Vineyard, is the furthest along; about half of the project’s planned 62 turbines have been installed and are sending power to the grid. Connecticut and Rhode Island’s shared farm, Revolution Wind, has installed about 70 percent of its planned 65 turbines. New York’s Sunrise Wind and Empire Wind, located off western and eastern Long Island, respectively, have begun preparing the seabed for turbine and transmission cable installation. Further south, the 176-turbine Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind, located about 25 miles outside the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, is expected to begin sending power to the state’s grid early next year.

Together, and running at full capacity, these seven farms should be able to power 2.59 million homes. That’s a substantial achievement for a country that had no offshore wind a decade ago. But it is a far cry from the Biden Administration’s goal of 10 million homes by 2030.

Opposing wind power of all kinds has been a cornerstone of President Trump’s domestic energy policy. On the first day of his second term, Trump issued an executive order temporarily withdrawing “all areas on the outer continental shelf from offshore wind leasing.” The order also required a review of the federal government’s leasing and permitting processes for wind projects.

The Trump administration has imposed a 50 percent tariff on wind turbine parts, most of which are made in Europe and China.

Following Trump’s order, the myriad federal agencies with a hand in regulating offshore wind moved quickly. In March, the EPA revoked the air quality permit for Atlantic Shores, a partnership between the oil giant Shell and the renewable energy company EDF Group, which was planning a project off the southern New Jersey coast that could have had up to 200 turbines. The EPA’s action was enough for Atlantic Shores to pull the plug on the whole endeavor. In a statement to E&E News following the project’s cancellation, a spokesperson for Shell said the company “will not lead new offshore wind developments.” And, just this week, another major oil company, BP, and its partner Jera Nex announced that they were pausing its only planned U.S. wind farm, Beacon, located off the Massachusetts coast.

In April, the Interior Department had issued a stop-work order to Empire Wind, the 54-turbine project in the early stages of development off Long Island, New York. Other than an almost entirely redacted 36-page draft analysis by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, presumably about Empire Wind’s impact on fisheries, no other information on the cause of the order was provided. Another stop order came in August, this time to Revolution Wind, the nearly completed 65-turbine farm located off the coasts of Rhode Island and Massachusetts. This time, the issuing agency was the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), which cited concerns about Revolution’s impact on national security. Other than the two-page order itself, BOEM provided no documentation justifying the decision.

Wind turbine parts for the Revolution Wind project site at a port in New London, Connecticut, last month.

Joe Buglewicz / Bloomberg via Getty Images

After direct negotiations between New York’s governor and top Trump administration officials, Empire Wind was allowed to resume construction in May. Revolution Wind was able to restart in September following an injunction issued by a federal judge. But significant economic damage was done. According to Kris Ohleth, director of the research group Special Initiative on Offshore Wind, the stop-work orders led to “several hundred people a day who are no longer working” and weekly losses for the companies that amounted to $20-30 million. Offshore wind developers right now “are essentially riding it out by laying off staff and going back to skeleton crews,” she said.

Under Trump’s “One Big Beautiful Bill,” the budget package passed by Congress in July, Biden-era federal tax credits for wind and solar developers, which would have expired no earlier than 2032, will now end in July 2026.This drastically shortened deadline spelled the end for the dozens of proposed offshore wind projects that were still in the planning stages, because, without the tax credits, they would be too expensive to build and maintain. To further jack up costs, the administration imposed a 50 percent tariff on wind turbine parts and components, most of which are produced in Europe and China.

Offshore wind development had already faced intense opposition from coastal communities and the fishing industry.

In addition to tax credits, the Biden Administration had made a massive investment in the onshore infrastructure to service the wind farms. Thirteen port projects were being built on both U.S. coasts, most of which were in the Northeast. The facilities would have served as marshalling grounds for the turbines’ massive towers, blades, and engines before being loaded onto specially built transport ships. Other sites would have manufactured some of the parts needed to construct and service the turbines, transmission stations, and electrical cables.

But, in August, Sean Duffy, the secretary of the Department of Transportation, canceled $679 million in funding for offshore wind, $177 million of which was designated for port development. The money would instead be redirected to ship building. “Wasteful, wind projects are using resources that could otherwise go towards revitalizing America’s maritime industry,” Duffy said.

No onshore location is at more risk than New Bedford, Massachusetts, where the largest commercial fishing port in the U.S. has been steadily transforming over the past decade into an offshore wind marshalling and manufacturing hub. Expansion plans for New Bedford have been scrapped or are on hold. “This was going to be a place that provided a substantial amount of jobs for a part of New England that is economically challenged,” said Elizabeth Wilson, a professor at Dartmouth College who studies the evolution of U.S. offshore wind energy. “You have all of these manufacturing facilities that were planned but aren’t happening, so all of those jobs no longer exist.”

A ship carrying parts for the Vineyard Wind project arrives to New Bedford, Massachusetts.

Rodrique Ngowi / AP Photo

To be sure, the U.S. offshore wind industry was already facing mounting challenges before Trump returned to office this year.

During the Biden years, offshore wind development was pushed along at breakneck speed. BOEM held six auctions that carved out over 30 offshore wind lease areas amounting to millions of acres of seafloor. In turn, states courted the streams of developers who had purchased the leases and needed to connect their farms to onshore transmission stations. In the case of some projects, seabed surveying — which uses sonar that could be loud enough to harm marine species, especially whales and dolphins — was conducted before environmental impact statements were done.

This ignited intense opposition from coastal communities and the fishing industry. Commercial fishermen argued that large swaths of their lucrative grounds would become off-limits due to habitat destruction and the risk of fishing gear being lost or damaged from snagging on transmission cables or other infrastructure. Some scientists and environmentalists, who otherwise supported clean energy, raised concerns about the cumulative impacts of thousands of huge, noisy turbines operating in the middle of the migration routes of critical marine and avian species.

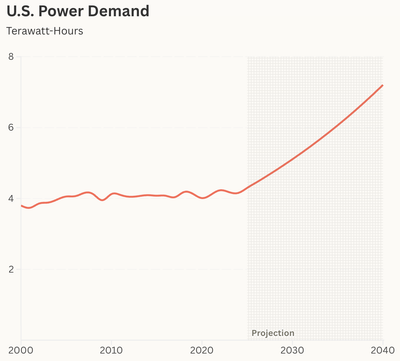

“Demand for electricity is growing nationally, driven by data centers that power the digital economy,” says a grid operator.

Most critically, though, the Covid-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine splintered the global supply chain, hiking the prices of many of the components needed for offshore wind development. The manufacturers were the first to back out of the U.S. market — in 2023, Siemens Gamesa scrapped plans to build turbine blades in Virginia, while turbine engine manufacturer Vestas failed to establish a facility at a New Jersey port that would have assembled nacelles — engines — for turbines. And, in January, the Italy-based cable manufacturer Prysmian informed Massachusetts that it wouldn’t be moving forward with plans to repurpose a plant that once housed a coal-fired power generator into an offshore wind transmission cable factory.

The most significant blow came in New Jersey in 2023, when the Danish developer Ørsted canceled two massive projects off the state’s southern coast. Rather than endure the increasingly turbulent market conditions and a relentless campaign from opposition groups, Ørsted wrote off $4 billion in losses and focused on its smaller New York projects, Revolution and Sunrise Winds. After Atlantic Shores pulled the plug on its farm earlier this year, New Jersey’s offshore wind portfolio was reduced to zero.

Based on historical generation data from the Energy Information Administration, with projections of future demand as forecast by McKinsey.

Yale Environment 360

The sinking fate of the U.S. offshore wind industry comes at an inflection point for energy producers and providers on the East Coast and elsewhere in the country.

At the Rowan University conference, Asim Haque, a senior vice president at PJM Interconnected, the Northeast U.S.’s grid operator and the largest in the country, noted that, after years of procuring energy supply far above projected demand, PJM just barely managed to secure the capacity it predicts it will need for 2026-27.

This, Haque said, is due to a confluence of factors. “Demand for electricity is growing nationally, driven by data centers that power the digital economy and the development of artificial intelligence,” he said in an interview. At the same time, Haque added, plants that generated power from fossil fuels or nuclear closed because they had either reached the end of the life cycle or were prematurely shuttered by state governments pushing to transition to renewable sources.

Many of the states in PJM’s footprint are a part of a regional power sharing agreement, which has allowed certain ones, like New Jersey, long unable to produce enough of the electricity it needs on its own, to buy cheap power from neighboring states with energy surpluses. (In 2024, the state imported more than 35 percent of its power.) Those days appear over. With the huge surge in demand, Haque said, states are keeping much more of their energy for themselves. High demand and limited supply, of course, equal rate hikes.

“Our current level of political and regulatory volatility does not support large projects that take a long time to build,” an expert says.

Ultimately, Haque’s message, as well as those of the other speakers at the Rowan conference, emphasized the need for an all-of-the-above approach to energy — a point that would have been anathema in previous years, when expectations for offshore wind and other renewable sources were high . “These policy swings over the last four or five years, for a grid operator that has to actually make sure that an electron is generated and delivered in real-time across a many-million-mile transmission system [that’s] trying to serve 67 million consumers — it’s very tough,” he said.

Wilson, the Dartmouth professor, said the effort to launch U.S. offshore wind provides lessons about the country’s ability to build huge, modern infrastructure of any kind.

“Our current level of political and regulatory volatility does not support large projects that take a long time to build and cost billions of dollars,” Wilson said. “Having a policy system that changes day-to-day doesn’t allow you to develop and invest in something that takes a decade to build.”

In the meantime, zero carbon energy advocates are facing a tough reality. “PJM doesn’t pick and choose its resource mix,” Haque said of his company. “We operate the grid based on what we’ve got.”