Three days after the Mountain Fire tore through the hillsides of Camarillo in Southern California last November, Craig Crosby was at home assessing the damage when he spotted two men canvassing the neighborhood. Crosby’s house was still standing, but the blaze had burned down the northwest corner of the structure and his avocado orchard. Every surface was covered in ash and soot. The windows had melted, the doors were scorched, and everything reeked of smoke.

The men eventually made it to his doorstep and introduced themselves as franchise employees of the national restoration company Servpro. They told him they could help with the cleanup, and that they worked with all major insurance firms, including AAA Insurance, where he held a policy.

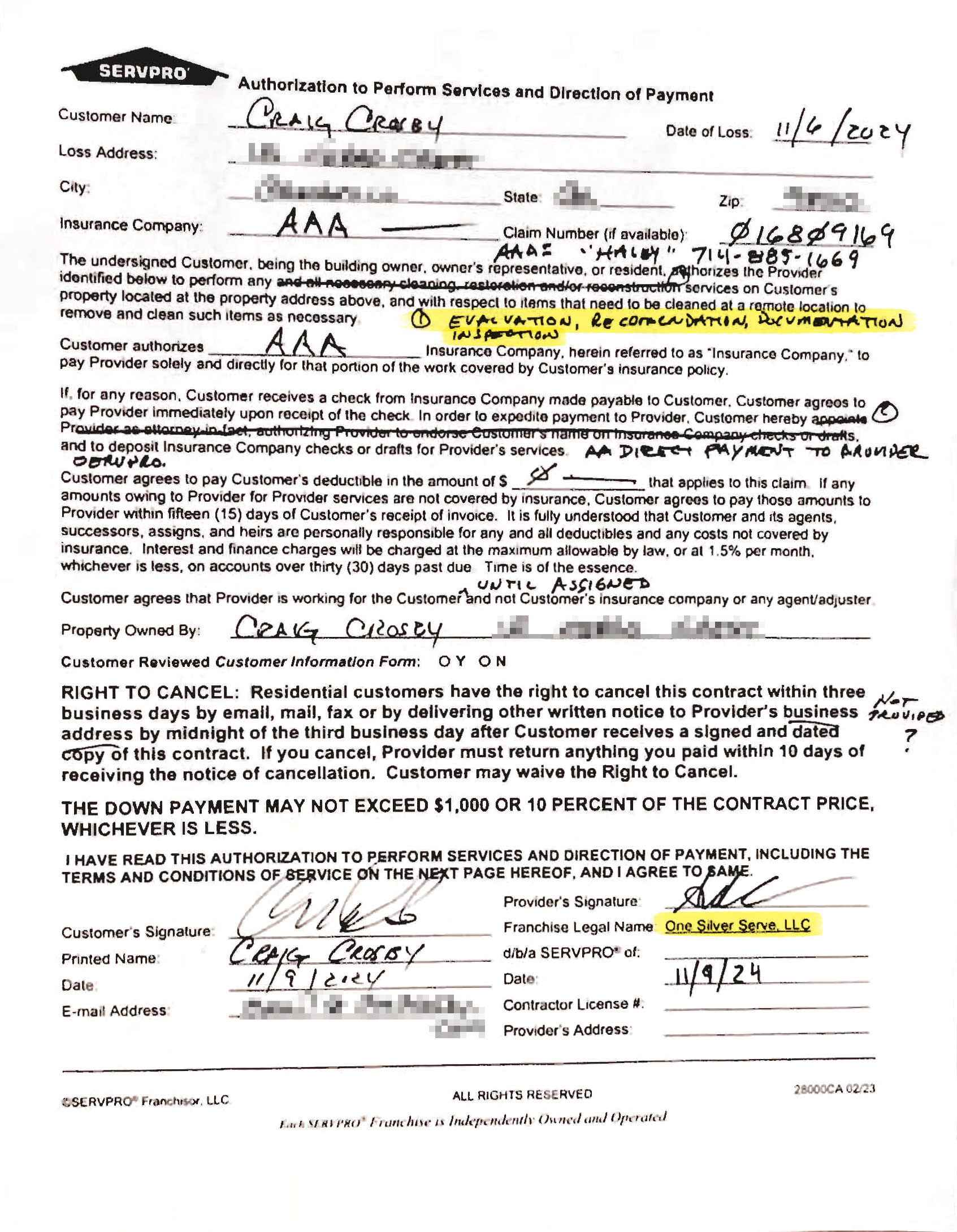

Crosby, who is a consumer advocate and founder of The Counterfeit Report, was wary. He told them he was not ready to authorize repairs, but that they could assess the damage. When they handed him a one-page access form, he scrawled a few amendments: his insurance adjuster’s information and a line clarifying that he only wanted “evaluation, recommendation, documentation, and inspection.”

“I like to memorialize exactly what I say,” Crosby later recalled. “And it struck me a little unusual that they didn’t have a problem with me changing a corporate form.”

Craig Crosby / Grist

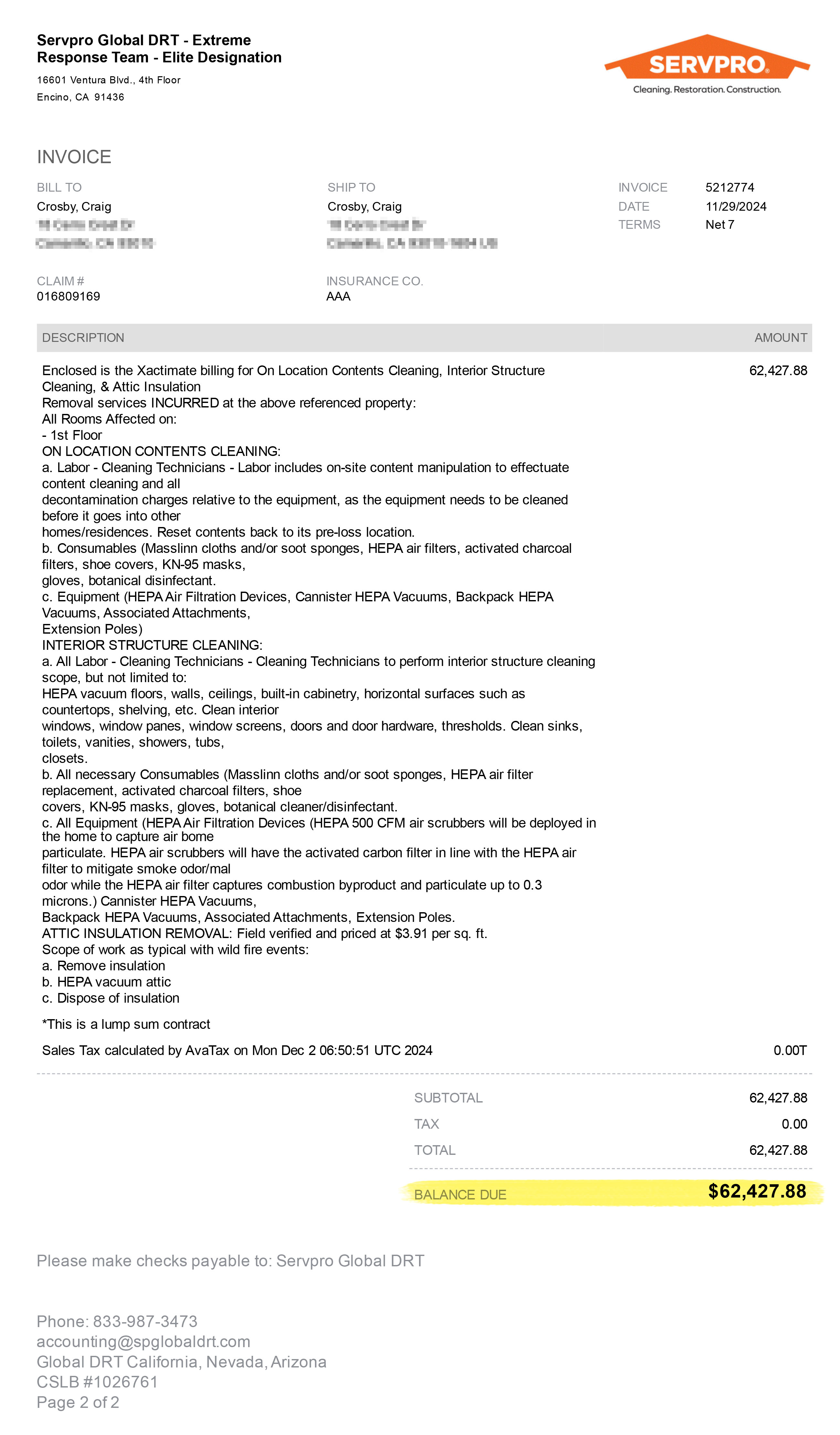

Over the next 10 days, the company sent more than a dozen workers to his house. They moved furniture, wiped the walls, and dusted surfaces. Along the way, they copied a AAA Insurance representative on emails, leading Crosby to believe that his policy would cover the work. But Crosby started to notice they were cleaning surfaces that probably needed to be ripped out and tossed. Then they began causing new problems. As they tore out insulation in the attic, they damaged HVAC pipes and vents. (An HVAC technician would later deem the system inoperable due to the damage.) They also dinged the garage door, stained carpeting, and broke an attic access door.

When Crosby called his insurance adjuster to complain about the company’s shoddy workmanship and excessive billing, he was shocked to learn that AAA had never approved the work. In fact, they told him One Silver Serve, LLC, the franchise that had approached Crosby, was on their internal blacklist. When he told the cleaning company it would cost roughly $16,000 to replace the HVAC system, they initially offered in writing to cover the cost if he signed a liability waiver. Once he did, the company reversed course. Instead of paying, its lawyer told him he owed the company more than $62,000 for their services.

Then, on Valentine’s Day, the company escalated it further. Its lawyer filed a mechanic’s lien — a legal claim against a property for unpaid work — on Crosby’s home. He couldn’t believe it. He’d never paid a credit card bill late, let alone had a lien on his property. “I pay all my bills a month in advance,” he said. “That’s how conscious I am not to jeopardize my reputation and standing.”

Based in Encino, California, One Silver Serve LLC is one of Servpro’s roughly 2,300 independently owned franchises. It benefits from Servpro’s national reputation, but operates with little direct oversight from the parent company. The quality of work, billing practices, and ethical standards are entirely left to the local franchise.

About a dozen of Crosby’s neighbors had similar experiences with One Silver Serve following the Mountain Fire, according to county records and court filings. Each was approached by workers at their doorstep in the days after the fire, told insurance would cover costs, signed an authorization form, and later received exorbitant bills for cleaning. Some, like Robert Perez, a funeral director down the street, received notice of a mechanic’s lien for roughly $58,000. When Crosby, Perez, and others didn’t cough up the money, One Silver Serve sued them in the Ventura County Superior Court. Crosby’s insurance adjuster eventually declared the home a total loss from the fire — a determination that restoration professionals typically identify during their initial assessment, before cleaning commenced. Crosby has since filed counterclaims for fraud, breach of contract, property damage, and elder abuse.

An attorney for One Silver Serve declined to comment. Kim Brooks, director of communications for Servpro, said the company is aware of the lawsuit against Crosby and does not comment on pending litigation.

More than a third of people impacted by a disaster report experiencing fraud, according to a survey commissioned by the American Institute of CPAs, a national organization of accountants. About 8 percent said they experienced contractor fraud, and another 10 percent reported vendor fraud, which involves improper payments to real or fictitious businesses. Post-disaster scams come in many forms. In some cases, contractors ask for money up front and then disappear. In others, they may tear down walls damaged by floodwaters or fires, collect a portion of their fees, and never return to rebuild the home. But in the case of more sophisticated actors, they use insurance companies and the legal system to put homeowners in a bind.

“Any component that involves people who have been impacted and are vulnerable, people will try to find a way to capitalize,” said Niambi Tillman, a regional director with the nonprofit National Insurance Crime Bureau. “You’ll see people price gouging or inflated costs with excessive billing, trying to convince people to make decisions very quickly and cough up money on the front end, and then not delivering the services.”

As hurricanes, wildfires, and flooding become more frequent and severe, the disaster economy has ballooned — and with it, opportunities to take advantage of people in crisis. Disaster survivors who have already lost homes, and in some cases, loved ones, are left further traumatized and financially strained.

The National Insurance Crime Bureau estimates that upward of 10 percent of post-disaster spending is lost to scams every year. With nearly $183 billion in infrastructure losses from weather-related disasters in 2024, contractor fraud has become a lucrative business. And its consequences ripple throughout the economy. The rising cost of recovery, fueled in part by fraudulent activity, then causes insurance premiums to rise and insurers to reduce coverage or leave a region altogether. According to the National Insurance Crime Bureau, fraud, particularly as perpetrated by contractors and other third parties, is “a threat to the stability of the insurance market.” USI Insurance Services, one of the largest insurance brokerage and consulting firms in the country, estimates that fraud is responsible for $900 more in premiums per policyholder.

One of Crosby’s neighbors, who asked for her name to be withheld, was not home when the Mountain Fire ripped through her neighborhood and burned part of her house. One Silver Serve charged more than $100,000 to clean the property — an amount she never agreed to — and put a mechanic’s lien on her house when she didn’t pay. Since the fire, she’s rented an apartment in the nearby city of Oxnard and has been coordinating repairs with a licensed contractor. For now, she’s focused on rebuilding and plans to deal with the lien afterward.

“In my whole 82-year-old life, I have never come across such absolute crooks,” she said. “Here you are, a devastating thing that your house … has burned, and they come and do this. It’s horrible. Right now, I don’t know how to get the lien off of my house.”

In the aftermath of wildfires, hurricanes, and flooding, state attorneys general, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and local law enforcement officials have taken to warning homeowners to be on the lookout for scammers. Servpro franchises aren’t the only offenders in post-disaster contractor fraud. But Servpro’s national reputation and professional branding lend an air of credibility to franchisees’ operations, making them harder to scrutinize.

Servpro was founded in 1967 as a small painting operation in Sacramento, California. Within two years, the company launched as a franchise cleaning business and began expanding its operations. By 2000, it had 1,000 franchises, and by the end of the decade, it made more than a billion dollars in revenue. Today, the company has a network of over 2,300 franchises and is a multibillion-dollar organization that can serve 97 percent of the country’s ZIP codes within two hours.

Smith Collection / Gado / Getty Images

Once franchisees are approved, they receive classroom and hands-on training at the company’s headquarters in Gallatin, Tennessee. The company requires that franchisees use Servpro-branded equipment and professional cleaning products, paint any service vehicles with the company’s green logo and decals, and wear its black and green uniforms. “Servpro has a proprietary brand identity guide that establishes and maintains a consistent professional customer-facing image for brand awareness and professionalism,” the company’s website notes.

But it’s unclear if Servpro has processes in place to hold franchise owners accountable for questionable practices. Across the country, there are hundreds of complaints with the Better Business Bureau and other consumer websites about price gouging, overcharging, and engaging in intimidation tactics by Servpro franchises. For instance, the Better Business Bureau profile for Servpro Northeast Salem in Oregon has multiple complaints of fraudulent liens placed on homes after the company damaged property and overcharged for work. Similar complaints exist for franchises in Naperville, Illinois; Douglasville, Georgia; and Marietta, Georgia.

In 2023, when a major storm blew through central California and dumped nearly 5 inches of rain over 24 hours, the floodwaters damaged Wee Shack, a family-run burger restaurant in Morro Bay, a seaside city near San Luis Obispo. The restaurant’s owner, Hoai Duc Ngo, hired Servpro of Morro Bay/King City for water and mold remediation. The company required him to sign a contract to receive an estimate and later told him the work would cost about $130,000 — nearly equal to his entire insurance coverage. When he refused to pay the charges, the company filed a mechanic’s lien against the property and sued him, despite the fact that they hadn’t provided an estimate up front, had done minimal restoration work, and had caused additional property damage. Ngo later had the work completed for about $15,000, and filed counterclaims against the company for negligence, misrepresentation, fraud, and concealment, among other charges.

Some franchises have also faced regulatory action. After Hurricane Florence hit North Carolina in 2018, Servpro of Boise, an Idaho-based franchise, sent workers to the region for cleanup. They approached residents of an apartment building that had suffered water damage, conducted cleanup, and then filed a lien and a lawsuit against the condo owners for $100,000 when they refused to pay what they saw as an exorbitant bill. The North Carolina attorney general’s office took on the case and ultimately settled with the company, canceling the outstanding lien and dismissing the lawsuit. (According to the Better Business Bureau, Servpro of Boise also includes a nondisparagement clause in its contracts with customers, prohibiting them from filing complaints or posting negative reviews.)

But the accountability that happened in North Carolina is rare. Since the rules and regulations for how contractors are required to operate change from one region to another, fraudsters often cross jurisdictional lines after natural disasters to seek out work in regions with the least protections. Amelia Hoppe, co-founder and executive director of Emergency Legal Responders, an organization dedicated to advancing civil rights and justice after natural disasters, said that homeowners need to be particularly careful about out-of-state businesses. “The vetting for local governments is really paying attention to who’s coming in from out of state,” she said.

In at least one case, the national Servpro headquarters does appear to have taken action against a franchise. After multiple complaints from customers of excessive billing, charging for work not performed, and intimidation, the company terminated its agreement in 2018 with Servpro of Rosemead/South El Monte, which operated near Los Angeles. When the franchise continued to operate with Servpro’s logo on a van, the company sued. A federal court ultimately sided with the national company. According to California records, Servpro of Rosemead/South El Monte’s business license is suspended, though where its owners and past employees have gone since is uncertain.

In Camarillo, One Silver Serve displayed red flags typical of fraudulent contractors, experts said. For one, door-to-door canvassing after a natural disaster, though common, can be a telltale sign of predatory behavior aimed at exploiting vulnerable homeowners. The practice is so prevalent among unscrupulous actors that state laws often require a three-day rescission period, giving homeowners and businesses a brief window to cancel contracts signed under pressure at their doorstep. California is one of the states with a three-day rescission period, and for contracts signed in regions with a disaster declaration, the law guarantees seven days to rescind the agreement.

“The lien tactic, especially, we warn about that a lot,” said Hoppe. “It’s legal leverage without informed consent. Even when it’s technically allowed, it often plays out as coercive. People are overwhelmed, underinformed, and don’t have good options.”

Another red flag was that One Silver Serve never provided Crosby an estimate of the damage or a scope of work before starting. Without a detailed breakdown of the planned repairs and their costs, the company could later demand virtually any fee it wanted, consumer advocates warned. In one Camarillo homeowner’s case, the bill they eventually received stretched dozens of pages, with line items like “clean baseboard,” “clean recessed light fixture,” and “clean closet organizer and rod.” None of those items needed cleaning at all — they had to be ripped out and replaced because of fire damage.

A final warning sign, experts said, is failing to confirm whether the insurance company has a track record with the contractor and will cover the repairs.

“A call to the insurance company, an estimate of benefits from the insurance company, these can be valuable checks on the validity of that relationship,” said Keegan Warren, executive director of the Texas A&M Health Institute for Healthcare Access, who has advocated for the role lawyers can play in identifying and combating harmful practices after a disaster.

For Crosby and others, their experience with One Silver Serve has left them shaken and mistrustful of the disaster-restoration industry. Crosby has since moved back into his house and has been slowly making repairs to the sections that were damaged by the fire. His neighbor, however, faces a longer road to recovery. She’s in the midst of securing permits to rebuild the deck and other parts of the house that burned down. She hopes to be back in her home by January.

“When you tell this story, it’s like, ‘Oh, come on, I had to be stupid,’” she said. “But it’s just unscrupulous. You lose your faith in humanity.”

Meanwhile, One Silver Serve continues to operate in Southern California. In January, after the Palisades Fire took 13 lives and burned more than 23,000 acres in and around Los Angeles, One Silver Serve filed at least seven lawsuits in the Los Angeles Superior Court for breach of contract and other allegations. It’s not clear how many of these cases are similar to the ones the company filed against homeowners in Camarillo.

In an April Facebook post, Servpro highlighted the work of its many franchises, including the cleanup One Silver Serve did after the Palisades Fire. “When Servpro franchises come together, wonderful work results,” the post said.