- Scientists used AI to analyze 20 years of satellite images and found that floating algae blooms are increasing worldwide.

- Large seaweed (macroalgae) patches and microalgal blooms have grown rapidly since about 2008–2010, showing a major shift toward more algae in the oceans.

- Floating algae can help marine life in open water, but when it reaches coasts, it can damage ecosystems, tourism and local economies.

- The increase is likely linked to climate change, warming oceans, changing currents and nutrient pollution from human activities.

Adapted from a press release by the University of Southern Florida

For the first time and with help from artificial intelligence, researchers have conducted a comprehensive study of global floating algae and found that blooms are expanding across the ocean. These trends are likely the result of changes to ocean temperature, currents, and nutrients, according to the authors, and could have a significant impact on marine life, tourism, and coastal economies.

Led by researchers at the University of South Florida (USF) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Columbia University and other institutions, the study demonstrates the power of artificial intelligence as a tool for processing large amounts of ocean data.

“With machine learning, we developed maps that clearly showed floating algae on the ocean was on the rise,” says co-author Joaquim Goes, a research professor at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, which is part of the Columbia Climate School.

“While regional studies have been published, our paper gives the first global picture of floating algae, including macroalgal mats and microalgal scum,” says Chuanmin Hu, professor of oceanography at the USF College of Marine Science and senior author of the paper recently published in Nature Communications. “Our results show that the global ocean now favors the growth of floating macroalgae.”

Hu refers to macroalgae, such as seaweed, as a double-edged sword. In open water, they can provide critical habitat for marine life and have a positive impact on fisheries, serving as a nursery for many species. But once the algae reach coastal waters, the decaying biomass can cause considerable harm to tourism, economies and the health of people and marine life.

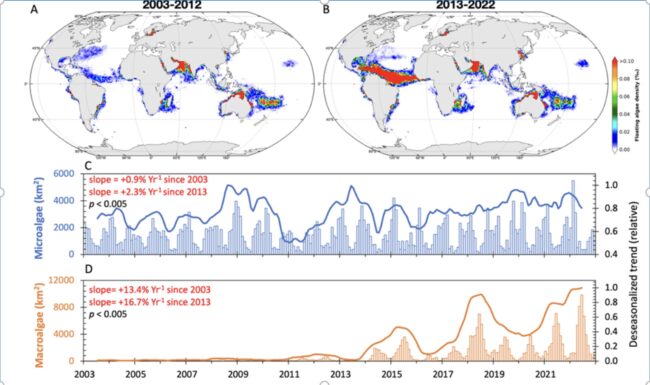

Between 2003 and 2022, both microalgal scum and macroalgal mats expanded around the globe. Microalgae on the ocean surface saw a modest but significant increase of one percent per year. However, blooms of macroalgae increased by 13.4 percent per year in the tropical Atlantic and western Pacific, the authors found, with the most dramatic increase in biomass occurring after 2008. The cumulative size of these macroalgal blooms reached 43.8 million square kilometers (16.9 million square miles), breaking with historic trends.

In the Indian Ocean, which is landlocked to the north, circulation is sluggish, says Goes. “You can see that the floating algae has increased three to three-and-a-half fold, which is really alarming.”

The tipping points for macroalgae blooms occurred around 2010. The first major bloom of the green seaweed known as Ulva happened in the Yellow Sea in 2008. A significant bloom of the brown seaweed Sargassum took place in the tropical Atlantic in 2011. Another Sargassum bloom occurred in the East China Sea in 2012.

“Before 2008, there were no major blooms of macroalgae reported except for sargassum in the Sargasso Sea,” Hu says. “On a global scale, we appear to be witnessing a regime shift from a macroalgae-poor ocean to an macroalgae-rich ocean.”

To conduct the study, the researchers used artificial intelligence to scan 1.2 million satellite images of the ocean, focusing on 13 zones and five types of algae. They trained a deep-learning model to spot features that signal the presence of algae floating on the ocean surface. In most cases, these features appear across many image pixels, but they typically comprise less than one percent of each pixel.

Lin Qi, an oceanographer at the NOAA Center for Satellite Applications and Research and first author of the study, updated a computer model previously developed by the same research team to analyze 20 years of images from the global ocean. It took several months and millions of image features to train Qi’s model.

The authors credit USF’s Research Computing department for its critical role in the study. The facility provided access to high-performance infrastructure that processed multiple groups of images simultaneously. Even still, it took several months to process and analyze the 1.2 million satellite images.

“This work is impossible without the high-performance computing facility or the long-term collaborations between NOAA and USF,” Qi says.

The study attributed the bloom expansions to both human activities, such as nutrient runoff into the ocean, and climate variability, such as ocean warming, while acknowledging that the reasons may differ among regions. Looking forward, Qi says, “we are going to explore more satellite data and look for better understanding of the expansions.”