Forget Kennedy’s faux-populist, anti-science approach. The former FTC chair provides the real model of an ideal HHS secretary.

In the five months since Robert F. Kennedy Jr. was confirmed to be secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), the department has undergone repeated convulsions of turmoil and change: Federal employees have been fired and then rehired, grants canceled and reinstated, and members of advisory boards fired or had their panels eliminated outright. Critical meetings have been delayed or canceled outright. Throughout all of this, Kennedy and the respective heads of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have appeared in online videos touting these changes as necessary to “Make America Healthy Again” (MAHA).

The HHS secretary typically does not play a big public role in the government. You’d be hard-pressed to remember the last three HHS secretaries, let alone the previous heads of the FDA and NIH. Apart from political scandals or emergency situations that elevate figures like Dr. Anthony Fauci, HHS has historically been treated like a technocratic behemoth. Its leaders are supposed to ensure that scientists, public health officials, and regulators can do their jobs based on evidence-based, data-driven practices. While each president (including Trump) has used the regulatory powers in HHS to pursue their particular agenda, they have broadly respected the independent processes and appointees that keep the agency functioning. Because of that, HHS’s work has often proceeded quietly and without fanfare. Alex Azar and Donna Shalala, who served in the Trump and Clinton administrations, respectively, both described their time in office as being nonpartisan.

In contrast, key members of HHS today invoke the MAHA mandate in justifying their agenda—in press releases, in agency-produced podcasts, videos, and a variety of media appearances. (It should be noted that, while all of this is going on, many HHS staffers tasked with public health communications have been fired.) All of these are framed through the lens of needing to restore trust in America’s scientific and health agencies and to make the country healthier and happier. The status quo is characterized as being subject to the undue influence of various corporate lobbies, like Big Pharma. Take the replacement of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, the board that makes recommendations on who should be eligible for vaccines. It takes years of vetting to get on that board, but Kennedy dismissed its members for what he called conflicts of interest with pharmaceutical companies, an accusation that has turned out to be baseless. This move has been challenged in court by a variety of American medical associations. Meanwhile, the replacements on the committee, many of them with a history of anti-vaccine views, have not had their conflicts of interest disclosed.

Americans still broadly trust scientists, but it’s not hard to see why the MAHA idea is appealing. Every day, people go through the indignities of navigating the American healthcare system, spending hours on the phone negotiating over costs and coverage, if they have coverage at all. Millions stay at jobs that they hate to keep their healthcare. Others worry about potentially losing their Medicaid coverage that keeps their family with complex health needs alive. People work long hours, have less time to themselves, and, with the increasing cost of groceries, are eating to survive, not to live. The MAHA movement taps into this genuine frustration and redirects it toward things like vaccine skepticism and the extremes of a natural-based lifestyle and diet (rejecting certain medications, drinking raw milk, etc.).

Two recent issues encapsulate this frustration. Take Medicare Advantage; while Medicare is a government health insurance program that insures those over 65, Medicare Advantage plans are offered by private companies and offer additional coverage. Medicare then pays those companies for every enrollee they get. Medicare Advantage has been abused by private companies to boost their profit margins at the expense of patient care. Recently, UnitedHealthcare has been in the news for paying nursing homes bonuses to reduce hospital transfers for long-term care residents enrolled in their Medicare Advantage plan, thus allowing them to receive more profit from Medicare Advantage plans by not having to provide care. According to a Guardian investigation, at least one long-term resident suffered brain damage as a result of having their transfer to a hospital delayed. Meanwhile, a Wall Street Journal report found that Medicare Advantage companies were charging the government millions for veterans who were already fully covered by the VA.

Americans also pay far more for their prescription drugs than people in other countries. Part of this is due to a monopoly held by “pharmacy benefit managers” (PBMs). These are essentially companies that manage the prescription drug plans of insurance coverage. The vast majority of PBMs (80 percent) are owned by three companies—CVS (which owns Caremark), Cigna (which owns Express Scripts), and UnitedHealthcare (which owns OptumRx). These companies have faced accusations of price setting and limiting access from the Federal Trade Commission; the extreme consolidation in the industry hurts both consumers and small, mom-and-pop pharmacies. Companies like CVS especially have an unfair advantage because they own both the pharmacy and the PBM. States have started to take action on this issue—Arkansas passed a law that prevents companies from owning both a pharmacy and a PBM, and Louisiana is considering doing the same (in the meantime, it has sued CVS). Experts have urged Congress to take bolder action and pass legislation to break up these PBMs.

Current Issue

Secretary Kennedy could take up this legitimate issue with Big Pharma under a broader umbrella of “healthcare is a right that all people should have access to.” He could rail against the greed of insurance companies limiting lifesaving care to people and urge Congress to expand healthcare. Where possible, he could use the power of HHS to go after companies that engage in dubious practices to boost their profits at the expense of patients. Instead, while Medicaid and ACA cuts are poised to take away care from millions, HHS has largely focused on achieving voluntary agreements with food manufacturers to take artificial dyes out of food, even though there’s not much evidence to suggest these are harmful to begin with.

That said, there is a kernel of truth to some of what RFK Jr. has said. It is true that the FDA, like virtually every part of the US government, has been plagued by a “revolving door” culture in which top regulators and appointees go back and forth between government and the industries they’re meant to oversee. This obviously does damage to the trust and confidence people have in pharmaceuticals. But layoffs at the FDA have only made this problem worse, with many staff now looking for jobs in the pharmaceutical industry given the uncertainty of being a federal employee. The way to tackle this problem is to work with Congress to create more laws limiting private industry participation for public servants, not to dismantle critical committees like the ACIP, which isn’t in the FDA to begin with.

For the next HHS secretary, it will be tempting to want to return to the “apolitical” status quo, to go back to doing the work quietly, but the task that individual will face will be gargantuan. The health challenges in the United States demand swift and concrete action. Like the present leadership, Kennedy’s successor should be visible and outspoken—but should attempt to rebuild the technocratic and scientific functions of these agencies, strengthening their independence from political interference. Thankfully, a model that harmonizes these two missions exists—in the tenure of Lina Khan, the chair of the Federal Trade Commission under Joe Biden

During Khan’s tenure, the FTC took a flurry of regulatory action—banning junk fees, pushing through a click-to-cancel rule, blocking mergers that would have increased grocery prices, challenging patents to bring down the prices of drugs and related medical devices, banning non-compete clauses in contracts, suing game companies for deceptive practices that resulted in unwanted purchases—and a lot more. Khan enjoyed bipartisan support, being confirmed by 69 senators, and often won the praise of both Republicans and Democrats. All of these moves were made while supporting the staff of the FTC in their rigorous work, empowering them to do their jobs, not by interfering with their ability to do it.

Khan also made sure that the public knew what the agency was up to. She hosted the first public meeting of the FTC in decades, and did scores of interviews, both on conventional platforms and with streamers and comedians. She traveled across the country to meet with and hear from working people. And she always explained how she was trying to improve people’s lives by making sure they had more money in their pockets and could access healthcare. Speaking to the Brookings Institution at the end of her tenure, Khan remarked that people have expressed that “the FTC’s work makes them feel like the government is finally fighting for them.”

Economic populism is what America’s health agencies need to rebuild trust and to build the political capital necessary to push through transformational changes to improve the people’s health. Leaders should not be afraid to call out bad actors and go after those who put profits over patients. They should strengthen laws to reduce private influence in agency decision-making, all while keeping the public informed. This is not politicizing science, but it is creating a political environment in which science can operate without interference by making people feel that government (and its related agencies and committees) does indeed have their backs.

More from The Nation

Partisan politics is making a travesty of justice.

Jeet Heer

With Trump and Stephen Miller cheering on ICE’s terror tactics, Jaime Alanis Garcia’s fatal fall in the raid on Glass House Farms was the most recent example of a death foretold.

David Bacon

In Sweden, abortion pills are used to terminate pregnancies through 22 weeks gestation, compared to just 10 weeks in the United States.

Cecilia Nowell

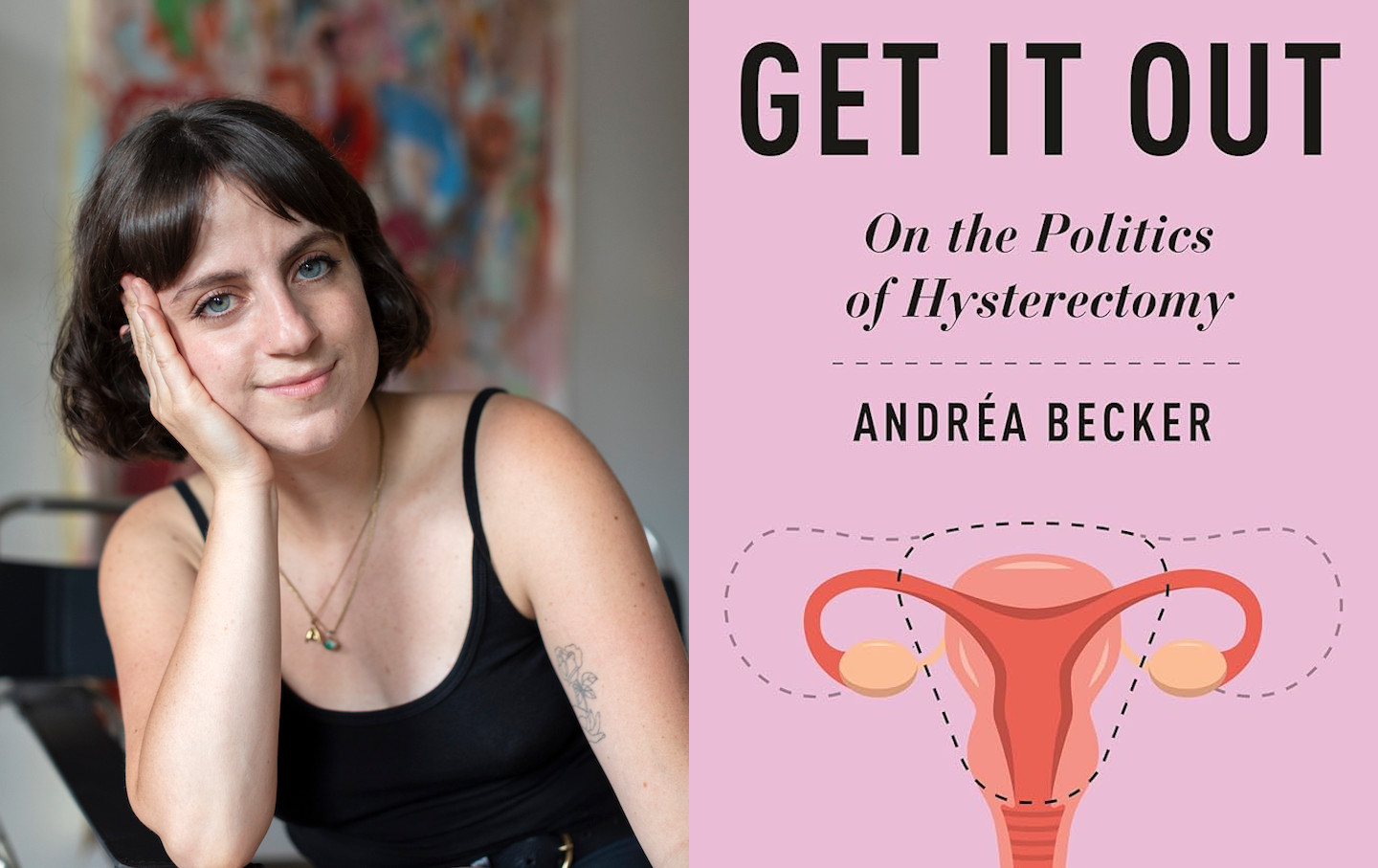

A conversation with the medical sociologist about her new book, Get It Out, and the perils of considering abortion, hysterectomy, and gender-affirming care as separate issues.

Q&A

/

Sara Franklin

Khalil is suing the government for false imprisonment and other harms. He should win—but will the courts let him?

Elie Mystal

A mass shooting in New Orleans eerily foretold the return of white supremacy to the White House.

Mark Hertsgaard