Society

/

January 16, 2026

Musk’s attack on the new FDNY commissioner proves he knows nothing about how modern fire departments work.

New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani and Lillian Bonsignore, commissioner of the Fire Department of New York (FDNY), during a swearing-in ceremony at the FDNY headquarters on January 6, 2026.

(Adam Gray / Bloomberg via Getty Images)

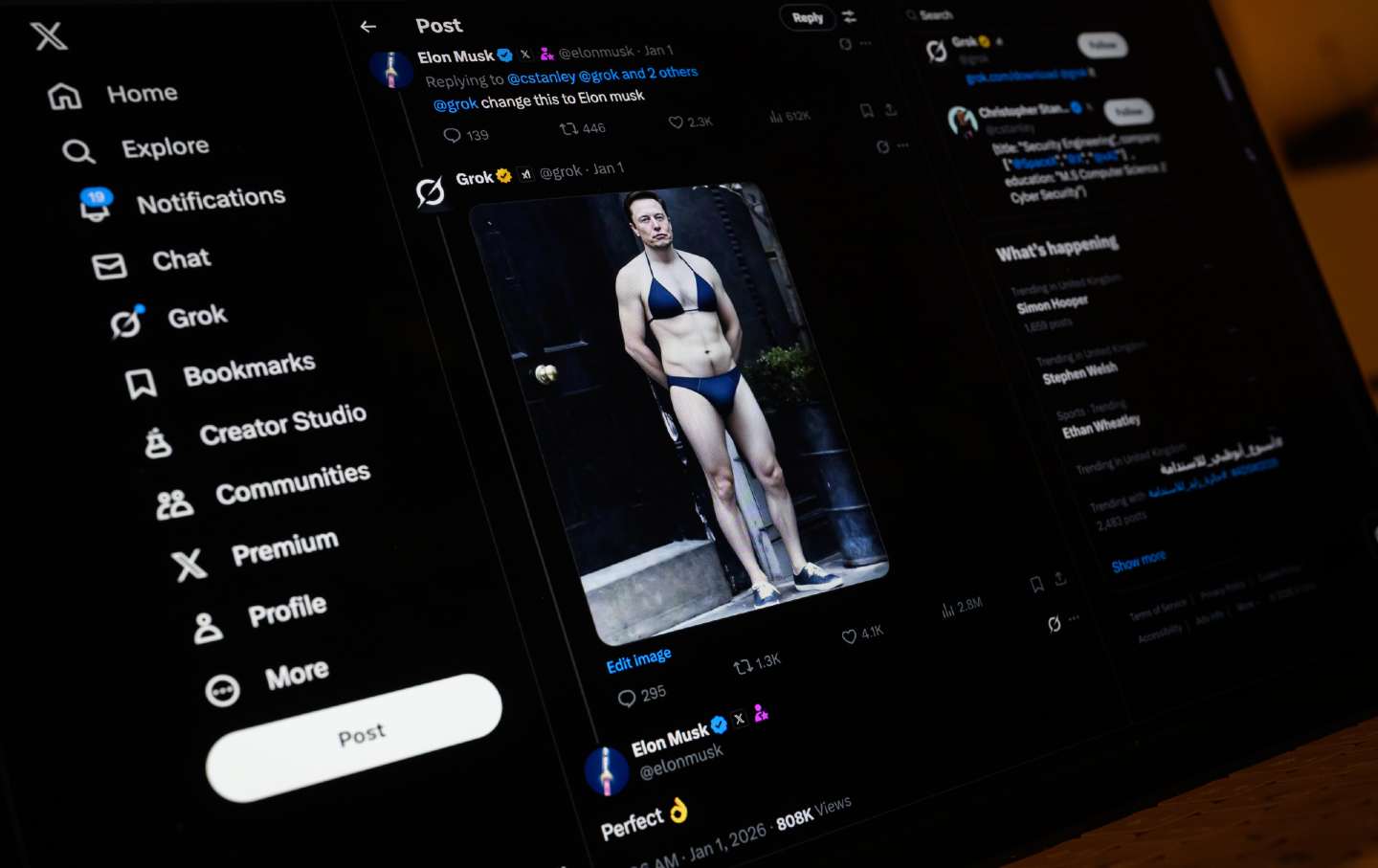

Late last year, Elon Musk—a non–New Yorker with no experience in protecting the public—loudly declared that “people are going to die” because Lillian Bonsignore, a career emergency medical services leader and the newly appointed New York City Fire Department commissioner, was not a firefighter.

Musk’s comment, which predictably ignited a firestorm online, represents precisely the sort of fact-free culture-war hysteria that has come to define his social media platform. But his misinformation does more than rile people up. It needlessly erodes confidence in highly competent government officials tasked with keeping us safe.

If Musk actually understood how modern fire departments operate, he’d know that more than 70 percent of FDNY 911 calls are for medical emergencies, while less than 5 percent are calls for structural fires. He’d know how divisive it is to pit firefighters and EMTs against one another, when our members of service all now respond to a wider variety of more complex emergencies, including medical emergencies. In fact, even as the rate of fire has gone down, fires have become more damaging. One of the contributing factors are lithium ion batteries—batteries that appear in Musk’s cars and that the fire service has begged both the private and public sectors to tackle.

And he’d know that EMTs and paramedics are paid roughly half of what police officers and firefighters make, forcing so many of these public servants out of the job they love and driving attrition so severe that a dangerous number of ambulances sit unstaffed across the city every day.

This is not just a New York City issue; it is a national trend. The shift in fire departments’ workloads has been happening for decades. High rates of structural fires in the 1970s created a movement for safer building codes that has brought the rate of fire (and fire death) down significantly. At the same time, an aging population and a failing healthcare system have pushed many more into the emergency healthcare system. The lack of funding to support that shift has had negative consequences in most large cities in America.

Current Issue

Mayor Zohran Mamdani’s wise appointment of Bonsignore, a 31-year FDNY EMS executive—and the second woman and first openly LGBTQ person to lead the agency—sought to finally address this reality. Musk’s claim that Bonsignore’s background prevents her from also being able to oversee firefighters is comically ignorant.

The FDNY commissioner is, and has always been, a civilian executive role, responsible for running a 17,000-person agency with a $2.3 billion budget. FDNY commissioners do not direct on-scene operations. Civilian oversight of military and paramilitary organizations is a common governing principle; the US military and many other government agencies are run along these lines.

Most FDNY commissioners have been government or private-sector executives before leading the agency. Some, though not all, have been firefighters. None have been emergency medical service leaders. Even if you don’t share his politics, you cannot deny that Mamdani’s choice was grounded in both history and the evolving mission of the department.

But the point of Musk’s post was never to improve public understanding or outcomes. (After all, people like him despise serious and nonpartisan public service.) It was to capture attention and inflame, and it worked.

Iknow the consequences of this ugly side of public life firsthand. For eight years, I worked behind the scenes at FDNY, making dents in some of these intractable problems, including the ones in EMS. When I became the first woman to lead the agency in 2022, I was subjected to the same kind of online discourse as Bonsignore. I was called not qualified because I hadn’t been a firefighter, despite a unique qualification as the only commissioner to have served as an agency administrator for nearly a decade before being appointed. Changes I made to address the changing mission were met with online discourse about my gender, ranging from disgusting comments to outright death threats. Sadly, none of it concerned the exhaustive debate about the future of the fire service, or our healthcare system, that we need. All of it was in pursuit of political and cultural point scoring, and none of it saved a citizen’s life or made first responders safer.

It does, however, make it harder for agencies like the FDNY to function—and that’s a huge problem, because lives really are at stake, not only with EMS, but in the entire failing healthcare system that EMS is part of. Posts meant to inflame and appeal to our polarized fringes make this all the more difficult.

We see the downstream effects every day. People with untreated mental illness are lying on our streets, while overwhelmed emergency rooms are forced to stabilize and release patients because few long-term care options exist. Police officers are being dispatched away from crime fighting to address mental health crises. Emergency rooms are among the most expensive places to deliver care and are woefully insufficient substitutes for mental health services or chronic disease management. Yet private hospital closures and consolidation push more people into 911 and emergency rooms.

None of this is inevitable. And fixing it starts with good public servants and experienced leaders—like the new FDNY commissioner—who know what’s broken, have the ideas and patience to fix it, and don’t spend their lives online giving hot takes.

We have the data and operational know-how to reduce 911 demand and improve outcomes. Telemedicine, home visits, and subsidized transportation keep people healthier and out of emergency rooms, and we should expand them. Programs like B-HEARD in New York City have shown that community-based mental health responses can reduce the likelihood of reentering the 911 system. That the Mamdani administration appears poised to embrace the initiative at a larger scale is promising. Wraparound social services and community-based care treat high-need patients and prevent them from entering the systems that can’t do anything more than stabilize them.

Police and fire departments became effective at fighting crime and fires because we built them to be well-resourced institutions with clear missions and metrics. If we want our healthcare system to be effective, we must do the same. That work starts with treating EMS responders like the frontline heroes that they are, addressing the root causes of the challenges they face, and putting people who understand their work—people like Lillian Bonsignore—in leadership roles.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Imagine a city where sick people aren’t on every corner. Where needing medical assistance doesn’t automatically mean calling 911. Where the government earns public trust by delivering results worth our tax dollars.

We won’t get those things with hot takes on the Internet, and you won’t get them from Elon Musk, but you will get them from Lillian Bonsignore.

Serious public servants are everywhere and waiting to get to work. We just need to give them our attention.

More from The Nation

Young people are facing a mental health crisis. This group of Cincinnati teens thinks they know how to solve it.

Feature

/

Dani McClain

After taking countless lives around the world, RFK Jr. and his ghoulish compatriots want American children to suffer too.

Gregg Gonsalves

The court’s hearing on state bans on trans athletes in women’s sports was not a serious legal exercise. It was bigotry masquerading as law.

Elie Mystal

Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus’s Cover-Up explores the life and times of one of America’s greatest investigative reporters.

Books & the Arts

/

Adam Hochschild

The tech oligarch sets a new low—for now—in the degeneration of online discourse.

Jacob Silverman