Lauri Myllyvirta.

Courtesy of Lauri Myllyvirta

Yale Environment 360: There are reports that China may have already hit peak emissions. Where are you seeing signs of that?

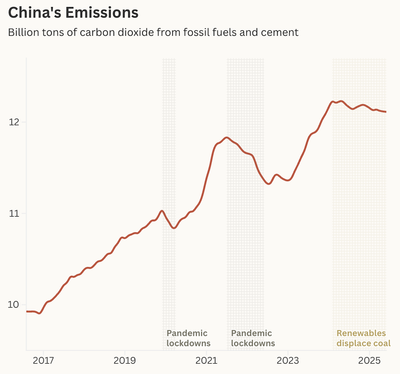

Lauri Myllyvirta: What’s very, very clear is that in the past couple of years, for the first time, the growth in clean energy generation has been big enough to cover all of electricity demand growth and then some. And that is even as electricity demand has been growing above the historical norm. Emissions from the power sector have been falling for 15 months. And that in itself is a hugely significant development. The big question now is will clean energy growth continue at these rates.

It’s clear that clean energy development in China has reached a scale where the country can hit peak emissions now if policymakers make choices that enable that to happen.

e360: What would those choices be?

Myllyvirta: The two biggest choices will be how to go about reforming the grid — China’s grid management is still quite outdated and rigid, and that will have to change if the country is to keep adding vast amounts of solar and wind. And the other question is, how do the policymakers react when the use of coal-fired power plants begins to fall sharply?

Since 2020, they’ve pursued this all-of-the-above, all-hands-on-deck response to the electricity shortages that they experienced from 2020 to 2022. China permitted a lot of new coal-fired power plants in the early years of this decade. And those projects are now beginning to be completed. So now we have a situation where demand for power generation from coal is falling because of all the clean energy coming on, and at the same time, those brand-new coal-fired power plants are starting to connect to the grid.

“We estimate that last year the clean energy industry was responsible for 10 percent of China’s economy and a quarter of its growth.”

That will mean the use of coal power will fall, and the profitability of coal-fired power plants will fall. And then decision-makers have to make up their minds about whether they want to start closing down some of those plants, or whether they will put brakes on the clean energy expansion to give the coal industry some breathing room. And that is, of course, a hugely consequential choice.

e360: Do you have any inclination about which way that’s going to go?

Myllyvirta: It is always going to be a muddling through. And the stakes are so high on both sides now. On the one hand, you have these powerful, influential companies on the coal industry side. On the other hand, the clean energy boom has been a major driver of China’s economy in the past few years.

We estimate that last year the clean energy industry was responsible for 10 percent of China’s economy and a quarter of its growth. So pulling the rug from under that industry would also be a major blow to the economy. But currently, the central government is still encouraging new coal-fired power plants because they think that capacity is needed in the grid.

China has previously seen its emissions drop during economic downturns. Now, for the first time, the growth of renewables is driving the decline. Source: Lauri Myllyvirta

e360: How powerful is the coal industry in China?

Myllyvirta: The coal industry is, of course, influential because of its role in local economies. You have a lot of cities that have sprung up only because they have coal. Still, the government has been willing and able to bypass the interests of the industry, for example, with the air pollution crisis more than a decade ago. The coal industry is definitely not all-powerful.

Mining — which is the main source of employment in the coal industry — halved its number of workers in less than a decade, simply because of mechanization and the closure of old mines. Every time people say that China should reduce coal consumption a bit, there are people who say, “What about all the jobs in mining?” But it’s really not about the jobs at all.

e360: In the past, China has been a laggard in international climate negotiations — it previously blocked a push to phase out coal. But now that it has emerged as the biggest clean energy producer, it seems it would have a strong incentive to push other countries to adopt more ambitious climate goals.

“China has been sluggish in backing initiatives that have a massive economic upside, like the target of tripling global renewable capacity.”

Myllyvirta: I think we’re seeing early signs of that. I think it was significant that this year President Xi Jinping took credit for China’s clean energy boom and started to communicate that to the rest of the world.

But China has still been quite sluggish in backing even initiatives that would have a massive economic upside for them, like the target of tripling global renewable energy capacity that was agreed to at U.N. climate negotiations two years ago. China didn’t block it, but it was not proactively or enthusiastically supporting it either.

I think that’s going to change, and I think one really important inflection point is going to be when China’s decision-makers have the confidence to say, “Now we have hit peak emissions. Now we’ve turned the corner, and we’re actually bringing our emissions down.” And that will mean China won’t need to be as defensive in international negotiations as they have been when they were the key driver of all the emissions growth. I think that will translate into a much more constructive and solutions-oriented approach.

A coal plant looms over a street market in Huainan, China.

Kevin Frayer / Getty Images

e360: In a recent analysis, you showed that China exported enough wind, solar, batteries, and EVs last year to cut global emissions by roughly 1 percent. It’s remarkable that China is exporting that much cheap clean energy.

Myllyvirta: The massive cost reductions that China has achieved in the past few years have made clean technologies much more attainable. The only way to do that is to sell a lot of them and produce a lot of them, and for manufacturers to compete against each other.

There certainly is unsustainable price competition in China at the moment. Solar and battery and EV producers are cutting prices to win market share and selling at prices that aren’t profitable. But most of the dramatic reduction in the cost of solar panels and batteries that we’ve seen in the past few years is due to genuine improvements in production and economies of scale.

e360: How might U.S. tariffs impact China’s clean energy sector?

Myllyvirta: Insofar as U.S. tariffs affect overall economic growth in China, that could play out in different ways. Since clean energy is such an important economic driver in China, when growth is weak, there’s even more of an incentive to boost the sector in order to hit economic targets and improve the economy in the short term.

“When the state broadcaster shows imagery of a modernized China in 2035, clean technology is a big part of that.”

But one important factor to keep in mind is that, in general, when China has faced economic headwinds, emissions have tended to go up because the government tends to respond by stimulating the most energy-intensive sectors of the economy, such as steelmaking. The current major role of the clean energy sector might have upended that dynamic a bit, but that’s still the clear historical precedent.

e360: The shift to clean energy is so contentious in the U.S. That doesn’t seem to be the case in China, even though coal is such an important industry.

Myllyvirta: I think it’s fascinating how clean technologies are a key part of the vision of a modernized China. When the state broadcaster shows imagery of a modernized China in 2035, which is the big aim of Xi Jinping, clean technology is a big part of that.

There are, of course, disagreements about the pace of change, how to manage the eventual phase-down and phase-out of the fossil industries, coal-based steel plants, and so on. But I don’t see anything like the polarization in the U.S., where there is this regressive idea that bringing back old, outdated, dirty technology would bring back the good old days.

e360: China isn’t looking backward.

Myllyvirta: There is no idealized past for the Chinese to look back to. They’re a very forward-looking, future-oriented people in that regard. There’s essentially no idea that horse-drawn carts or gasoline-fueled vehicles would somehow bring back the good old days.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.