“Countries are committing to buy lots of U.S. energy,” says an analyst. “I would call it a step change.”

“It will be the biggest year ever for U.S. LNG,” says Douglas Hengel, a senior consultant to industry trade group LNG Allies and adjunct faculty member at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies. “There seems to be a lot of interest in U.S. LNG, even aside from it being promoted in trade negotiations. Countries are committing to buy lots of U.S. energy.”

“I would call it a step change,” he says.

One reason for that bullish outlook is Trump’s reversal of a Biden administration freeze on permitting. In January 2024, after months of pressure from climate advocates, President Biden paused reviews of projects seeking to export gas to countries that do not have free trade agreements with the U.S., in order to fully study their climate and economic impacts and assess whether they were in the “public interest.” In December, a month before Trump took office, the Department of Energy (DOE) releasedits report finding that those LNG facilities would lead to increases in greenhouse gas emissions, domestic energy prices, and exposure to pollution in local communities.

On his first day in office President Trump reversed that order, directing the DOE to resume permitting LNG projects as part of his “Energy Dominance” agenda. In May, the DOE issued a revised version of the Biden-era report, dismissing the risks that the gas export boom would result in both more climate-warming pollution and steeper costs for U.S. gas consumers.

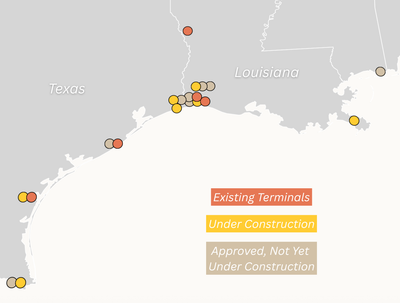

LNG export terminals on the Gulf Coast. Source: FERC.

Yale Environment 360

“It was a huge shift on day one from the Biden administration and the ‘pause’ to the Trump administration,” Hengel says. Developers of LNG projects need billions in financing from banks, which require proof that they have signed up enough buyers of future shipments of gas. “Some contracts were not yet agreed but close, but [buyers] wanted to be sure that the pause was lifted,” he says. “So, it has a practical impact.”

The Trump administration’s trade policies are generating another possible tailwind for the industry, one that could push more long-term purchase deals over the finish line. U.S negotiators have wielded the threat of tariffs to pressure trading partners into pledging to buy more gas from American exporters.

During the final stretch of trade negotiations between the U.S. and the European Union, Venture Global inked a 20-year contract with Eni, a major Italian energy company, for its new CP2 project. And in late July, the White House announced that the EU had committed to buying a staggering $250 billion worth of U.S. liquefied natural gas, oil, and nuclear fuel each year through 2028. The news sent the stock prices of Venture Global and Cheniere, the largest U.S. LNG exporter, surging.

As part of another recent trade deal, South Korea “agreed to purchase $100 billion in U.S. LNG or other energy,” according to President Trump, over an unspecified time frame. In another bilateral agreement, Japan agreed to “explore” a potential future investment in a proposed massive LNG export project in Alaska.

Advocates are concerned that countries are caving in to the Trump administration’s demands that they buy more U.S. gas.

But Seb Kennedy, a veteran gas market analyst who writes the Energy Flux newsletter, contends that, for the LNG sector, Trump’s approach to trade is “laced with contradictions.” Tariffs are already driving up the cost of steel and other materials needed for construction of LNG storage tanks, pipelines, and ships. Economists have forecast that the Trump administration’s tariffs will, on balance, result in slower global economic growth, which in turn could dampen demand for energy.

“U.S. LNG projects will be more expensive to build and find it harder to get buyers to commit to long-term contracts because it’s such an unstable, unknowable demand horizon,” says Kennedy. “It’s like kryptonite for the LNG space.”

Some analysts also question the concrete benefits of vaguely outlined energy provisions in these trade deals.

“What I have observed about all these trade announcements, especially the energy parts, is that there is very little data behind them,” says Anne-Sophie Corbeau, who tracks gas markets as a global research scholar at the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs.

For one, they may not be enforceable: These agreements are between governments, which can’t simply force private firms to sign contracts. And the numbers in the U.S.-EU trade agreement elicited skepticism from experts, who noted that its targets weren’t physically or financially feasible.

The Venture Global Plaquemines gas export terminal under construction in Port Sulphur, Louisiana last year.

Bryan Tarnowski / Bloomberg via Getty Images

“Even if we take into account that some Russian energy [consumed in Europe] is going to be replaced by U.S. energy, the numbers don’t add up,” says Corbeau. The value of U.S. LNG imported by Europe in 2024 was less than $20 billion, she points out. “Explain to me how we are going to reach $250 billion per year?”

The U.S. government’s strategy for meeting that target entails playing up allies’ geopolitical constraints while downplayingclimate concerns. Energy Secretary Chris Wright attended the world’s largest annual gas conference in Italy this month, where he pressed European officials to back away from their climate targets and loosen their new regulations on methane emissions of energy imports.

Such appeals may find a receptive audience. The war in Ukraine has made countries in Europe and beyond increasingly mindful of their own energy security, analysts say.

Climate advocates are concerned that countries are caving to the Trump administration’s demands that they import more U.S. fossil energy — and abandon their own emissions reductions plans in the process — in order to escape punishing tariffs.

The bigger climate risk is that building more LNG infrastructure could slow the global transition to renewable energy.

Lorne Stockman, the research co-director at clean energy advocacy group Oil Change International, says it’s important that European Union members rigorously apply new regulations that require companies to measure, report, and verify their methane emissions from LNG imports. Amidst reports that U.S. LNG lobbyists and Trump officials have been asking European regulators to water down these rules, Stockman insists that U.S. companies shouldn’t get a “free pass” because they can’t meet the EU’s criteria for low rates of methane leakage.

The overall climate impact of increasing LNG exports depends on how much methane leaks on its journey from wellhead to export terminal, tanker ship, and regasification facility. Because methane traps much more heat than carbon dioxide, the climate benefits of generating electricity from natural gas instead of coal vanish if enough escapes to the atmosphere. Estimates of leakage rates vary between countries and different oil and gas basins, but scientists have consistently found that methane emissions from U.S. oil and gas fields are substantially higher than figures reported by the EPA and the industry.

But the bigger climate risk is that building more LNG infrastructure could slow the global transition to renewable energy, resulting in higher carbon dioxide emissions. Stockman was a coauthor of a recent report from Oil Change International, Greenpeace USA, and Earthworks that analyzed the climate effects of five new U.S. LNG projects, including Venture Global’s CP2. Applying the methodology used in the Biden administration’s 2024 DOE study, the researchers found that each project would result in a net increase in global greenhouse gas emissions under any scenario, regardless of how much they reduced methane leaks or incorporated carbon capture and sequestration technology.

A new gas import facility in Wilhelmshaven, Germany.

Sina Schuldt / picture alliance via Getty Images

In the past, Stockman says, industry and government analyses of LNG projects’ climate impacts assumed that U.S. gas would substitute for heavily emitting sources such as coal or Russian pipeline gas. But “as wind, solar, and batteries become more and more commonly used and prices go down and economies of scale increase, you can’t just assume that LNG only displaces coal and other gas,” he says. “This analysis shows that it also leads to less wind and solar in the energy mix — and therefore increased exports always result in a net emission increase.”

Some analysts are forecasting that, by the end of the Trump administration, the world will have a glut of LNG supply — and the U.S. gas export sector could see its boom become a bubble.

The next wave of U.S. LNG projects seeking permits, buyers, and investors is largely predicated on forecasts of ever-rising gas demand in fast-growing Asian markets. But the plunging costs and accelerating deployment of solar is set to upend the assumptions underpinning those predictions, according to Christopher Doleman, a researcher at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis who specializes in Asia. He and other experts already see signs of a dramatic shift underway in the region.

“China and India are saying, ‘We’re not doing it that way. We’re using utility-scale renewables to reduce our peak emissions.’”

In Pakistan, thanks to an influx of cheap solar panels from China, demand for gas for electricity generation has plummeted to the point that Pakistan is asking Qatar, its main supplier of LNG, to delay shipments for the next few years. Even Japan, one of the world’s leading LNG importers, is lowering its outlook for natural gas imports, due to plunging demand from electricity generators. And according to Kpler, a data-tracking firm, China’s LNG imports have been declining for 10 straight months, and are 9 percent lower than this time last year.

Asia’s appetite for U.S. gas in the next decade could prove much smaller than projected by the industry, because it is relatively expensive compared to other sources (such as Qatar, a huge LNG exporter) and, increasingly, compared to renewable energy. And many countries, analysts say, are wary of getting locked into dependence on one fuel source. “Particularly for developing economies in Southeast Asia, it’s a massive fiscal burden if you make these commitments to buy LNG,” says Kennedy.

In the U.S., coal’s shares of electricity production and carbon emissions were slashed by cheap natural gas unleashed by the shale fracking boom. Doleman sees a different story playing out in Asia’s biggest markets. “China and India are saying, ‘We’re not doing it that way. We’re using utility-scale renewables to peak and reduce our coal usage and emissions.’”

Euan Graham, a research analyst at Ember, an energy think tank, believes these trends mean that investors in new U.S. LNG projects should tread carefully. “There’s a hell of a lot of risks in banking your business model on a sustained boom and structural rise in gas demand,” he says.