We conducted a comprehensive literature review and collected data from government databases to characterize the current state of the Brazilian pharmaceutical market. Our description covered population health issues, health system characteristics, and financing. The inclusion criteria incorporated keywords such as medications, pharmaceutical market, access to medicines, official laboratories, pharmaceutical market transition, productive development partnership, and patents. Our sources included scientific journals from major national and international databases, technical books from stakeholders, and relevant legislation and government reports from the Ministry of Health, including agencies such as the Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency (Anvisa), Medicines Market Regulation Chamber (Cmed), and National Committee for Health Technology Incorporation at the SUS (Conitec).

Epidemiology

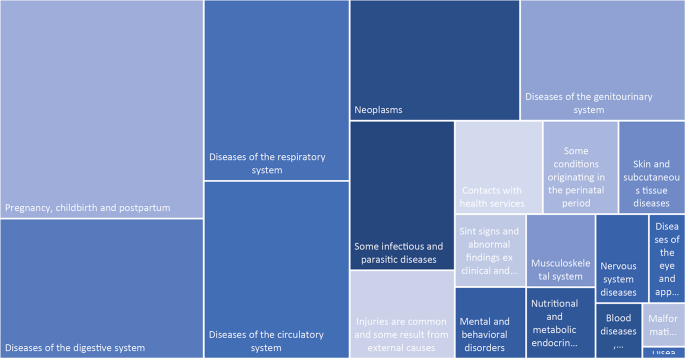

Among the leading causes of death in Brazil are diseases of the circulatory system, accounting for 25·9% of deaths, followed by cancer at 15·8%, diseases of the respiratory system at 11·4%, and infectious diseases at 8·5%. However, external causes of morbidity and mortality, related to such factors as violence, represent about 10% of deaths in the country. These data highlight the need for integrated approaches to prevent and control these various health conditions (Graph 1) [3].

Causes of death in the Brazilian population by international classification of diseases chapters, 10. Brazil, 2022

Unified health system

Established by the 1988 Federal Constitution, the SUS is grounded in the principles of universality, comprehensiveness, and equity. As the world’s largest universal public health system, SUS ensures free access to health care services and essential medicines for all citizens. Its structure is decentralized, with responsibilities shared among federal, state, and municipal governments. The system is primarily tax-funded and offers most services at no direct cost to the patient [4].

Brazil also maintains a supplementary private health sector, financed through private insurance, direct payments, or corporate plans. This coexistence results in dual access pathways: public provision via SUS and private acquisition. The SUS is the main provider of hospital care in Brazil, accounting for approximately 64% of all hospital admissions — about 13 million per year. In 2023, the leading causes of hospitalization included pregnancy, childbirth, and puerperium (16•8%), external causes of morbidity and mortality (11•1%), diseases of the digestive system (10•8%), respiratory system (9•9%), and circulatory system (9•7%) (Graph 2) [3].

Hospitalizations in SUS by International Classification of Diseases chapters, 10. Brazil, 2023

While the SUS is primarily tax-funded and offers free access to services, the supplementary system is financed through a combination of private and public sources and may provide access to medicines, depending on the coverage.

Pharmaceutical assistance

Medicines within SUS are dispensed through public health facilities, while private access often involves copayment or full out-of-pocket spending. Pharmaceutical assistance within SUS is structured into three main components, each aligned with the level of care, disease complexity, and funding mechanisms. The Basic Component of Pharmaceutical Assistance (CBAF) covers medicines for common conditions typically managed in primary care, such as hypertension and diabetes. The Strategic Component (CESAF) provides medicines for diseases of public health importance, including tuberculosis, HIV, and leprosy. The Specialized Component (CEAF) supplies high-cost and complex medicines, often related to chronic, rare, or autoimmune diseases, and is generally associated with secondary or tertiary levels of care.

The Brazilian also have a model called Farmácia Popular Program, which provides selected medicines and health products at subsidized prices in private pharmacies through public-private partnerships. This mixed provision model requires context-specific understanding, especially compared to countries where copayment or insurance-based systems dominate [5].

Financing and access disparities

This discrepancy between the demand for medications and the SUS’s capacity to meet it represents a key challenge for Brazil. The financing of medicines in Brazil involves a complex interplay between the public and private sectors, with the government, particularly through the SUS, serving as the larger purchaser. Budget constraints pose challenges to the government’s ability to fully fund pharmaceutical assistance. Brazil’s public health system relies on tax and social contribution resources at federal, state, and municipal levels. There are minimum financing thresholds corresponding to a percentage of tax revenue and funds distributed by the central government to lower levels of government (states) determined by amendment to the country’s constitutional text.

In 2021 the general health expenditure was 9·7% of the GDP, with the general government health expenditure making up 41·6%. The remaining 58·4% would have been covered by private spending, which includes out-of-pocket expenses by individuals, private insurance, and other non-governmental sources. Despite this, Brazil’s health care spending on medications remains relatively low compared to higher-income countries at 1·9% of GDP, with a substantial portion of medication financing coming from the private sector [6]. This peculiarity positions Brazil among the few countries with a nationally organized health system with universal coverage but with a predominant role played by the private sector. This structural imbalance between public and private financing reflects broader global challenges, particularly in countries with universal health systems facing increasing pressure from high-priced technologies.

Considering that a large part of the Brazilian population has the SUS as the main source to access healthcare, equitable access to medicines is still strongly compromised by the low availability of essential medicines as SUS distributes these technologies. In addition, almost 70% of the acquisition of medicines is made through direct disbursement by the population [6] also resulting in high rates of judicialization to obtain them.

From research to access

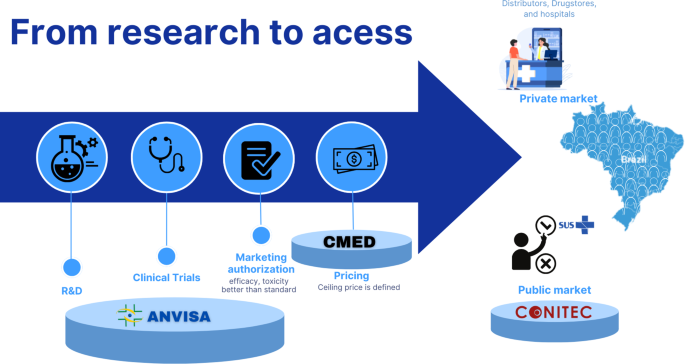

Getting medications to patients is a complex process involving multiple regulatory stages (Graph 3). Anvisa is the central authority responsible for regulating medicines, ensuring their quality, safety, and efficacy before they are authorized for commercialization. Anvisa also authorizes clinical trials, evaluates dossiers for marketing authorization, and oversees post-marketing surveillance. Like many other regulatory authorities worldwide, Anvisa aligns its regulatory processes with international harmonization standards, such as those issued by the International Council for Harmonization and the World Health Organization (WHO). This ensures regulatory convergence and facilitates the adoption of internationally accepted quality, safety, and efficacy criteria.

Infographic of the medication life in Brazil. Note: Anvisa – Brazilian Health Regulatory agency. CMED – Drug market regulation chamber

The institution operates within the broader structure of the National Health Surveillance System, which includes federal, state, and municipal authorities. The state and municipal components are responsible not only for inspections but also for implementing surveillance policies and conducting risk-based health monitoring. Their role encompasses surveillance of health services and products, guidance to health professionals, and the enforcement of regulatory compliance across healthcare facilities and pharmaceutical establishments.

From 2013 to 2023, Anvisa registered 1,974 clinical studies, with an increasing annual trend and an average of 141 studies per year [7]. For a drug to receive marketing authorization, its regulatory dossier must demonstrate quality, safety, and efficacy. The comparative evaluation with a standard treatment is not mandatory in all cases; it depends on the nature of the submitted evidence [8, 9].

As seen globally, the lack of comparators, the increasing use of expedited approval pathways and reliance on surrogate endpoints, rather than clinically relevant outcomes, has raised concerns regarding the real-world effectiveness of newly approved therapies [10].

As of December 2023, there were 10,125 medicines with marketing authorization in Brazil. Of these, 80.1% (n = 8,201) contained a single active pharmaceutical ingredient, representing 1,328 unique substances across various pharmaceutical forms and presentations. The most frequent therapeutic classes were antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents (17.8%), alimentary tract and metabolism (13.0%), nervous system (13.0%), anti-infectives for systemic use (11.4%), and cardiovascular system (8.3%) [7].

Research & development

The National Policy on Science, Technology, and Innovation in Health, reformulated in 2008, became an integral part of the national health policy and aims to foster sustainable national development. It does so by promoting the generation of technical and scientific knowledge aligned with Brazil’s economic, social, cultural, and political context. Initiatives led by the Ministry of Health to broaden access to technologies for prevention and care include efforts to stimulate the production and distribution of strategic technologies. One major strategic framework is the Economic-Industrial Health Complex, which seeks to integrate industrial development with public health needs as defined by SUS, focusing on areas such as vaccines, biotechnologies, and essential medicines [11].

Both public and private institutions conduct research and Development (R&D) activities. However, Brazil still faces challenges in fostering pharmaceutical innovation. R&D investment remains comparatively low, particularly in the development of drugs tailored to local health needs. One key limiting factor is Brazil’s heavy dependence on imported active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs)—with only around 15% produced domestically [6]. API costs may account for up to 80% of a drug’s total production cost [12].

The development of the national pharmaceutical industry has followed divergent paths. While the innovative pharmaceutical sector experienced growth in the 2000s, the generic drug market has increasingly lost ground to multinational companies. Despite being the largest pharmaceutical market in Latin America, Brazil has accumulated a significant trade deficit [12]. In 2023, pharmaceutical imports totaled USD 7.2 billion, while exports reached only USD 519 million, generating a deficit of USD 6.7 billion [13]. This pattern mirrors broader global market asymmetries, where a small number of transnational corporations dominates high-value segments such as biotechnology and innovative pharmaceuticals. Consequently, middle-income countries like Brazil often struggle to establish competitive innovation ecosystems, despite having large domestic markets [14].

Patent protection remains a key incentive for private sector innovation, but also creates barriers to access, especially during exclusivity periods when prices are highest. Although compulsory licensing is permitted under the World Trade Organization’s Doha Declaration, it remains rarely used. Brazil’s 2005 compulsory license for antiretroviral drugs is one of the few successful examples globally, underlining the potential of such legal tools to improve access to essential medicines [15].

Another barrier is the delay in patent examinations by Brazil’s National Institute of Industrial Property, which has been criticized for limiting pharmaceutical investment due to a backlog of applications and a shortage of examiners [16]. Although Anvisa’s prior consent for granting pharmaceutical patents was introduced in 2001, as a public health safeguard to align industrial property with health needs, this requirement was eliminated in 2021 [17, 18]. The removal of this mechanism may affect how public health considerations are integrated into patent decisions.

Brazil’s position in global pharmaceutical patent filings remains modest. In 2022, only 6.5% of the country’s 6,909 patent applications were for pharmaceutical products. Brazil ranked 54th out of 132 countries in the Global Innovation Index 2022, reflecting persistent structural barriers to advancing pharmaceutical innovation [19].

Drug pricing

In Brazil, once a medication obtains marketing authorization from Anvisa, its commercialization is subject to price regulation by the CMED [20]. CMED is responsible for defining price ceilings and monitoring the dynamics of the pharmaceutical market with the aim of promoting pharmaceutical assistance and stimulating both competitiveness and access to medicines. Its regulatory framework includes distinct provisions for public and private sector pricing, tax considerations, and periodic updates to reflect economic conditions [20].

Classification categories are used to establish maximum prices for new pharmaceutical products. New medicines are classified under Categories I or II. Category I applies to products with patented active ingredients in Brazil that demonstrate proven therapeutic benefits—such as increased efficacy, fewer side effects, or lower overall treatment costs. Category II encompasses new products without clear therapeutic advantages. Other categories (III–VI) cover new presentations, fixed-dose combinations, and generic medications. Omitted cases, such as orphan drugs, are decided by CMED’s Technical-Executive Committee [21].

To request pricing approval, companies must provide detailed documentation, including international reference prices, cost of the API, projected number of patients, proposed market price, tax burden, estimated marketing expenses, and prices of existing substitutes. External reference pricing includes comparisons with up to ten countries, among them Australia, Canada, Spain, the United States, France, Greece, Italy, New Zealand, Portugal, and the country of origin [20].

CMED’s regulation distinguishes between the Maximum Price to the Government (MPG) and the Maximum Price to the Consumer (MPC) for the private market. The MPG is subject to a mandatory discount coefficient, which is periodically updated and applies to medicines purchases made by the SUS. Additionally, different federal and state taxes apply to medicines—ranging from 12–22%—depending on the product type and state of sale [20].

Affordability, sustainability, and innovation are important policy goals broadly pursued in the national pharmaceutical policy. However, these are not direct, explicit criteria in CMED’s pricing methodology. The system seeks to promote competition and predictability, enabling manufacturers to offer commercial discounts within established price ceilings [14].

While this model has contributed to the containment of pharmaceutical inflation and increased market access, new challenges has appeared. Structural factors—such as high interest rates, exchange rate volatility, and dependency on imported APIs—limit national innovation and industrial autonomy. Recent shifts in the global market, including reduced availability of generics and increased reliance on high-cost therapies, have led to inflation in drug prices surpassing both general and healthcare-specific inflation indices [11].

Furthermore, the global trend toward approving high-cost medicines based on limited clinical evidence poses an additional challenge. These products, sometimes lacking robust comparative data, may receive premium prices without a clear demonstration of cost-effectiveness [33].

Additionally, the reliance on international reference pricing can further reinforce elevated prices set in high-income countries, exacerbating inequities in access. To promote affordability and sustainability, pricing and regulatory frameworks must evolve to better assess therapeutic value, safeguard against excessive costs, and strengthen national negotiation power in a context of increasing global interdependence [33].

National pharmaceutical market

The Brazilian pharmaceutical market is highly concentrated, with a few large companies dominating a substantial share that can impact prices and access, particularly concerning essential medicines. In 2018, Brazil boasted 450 pharmaceutical companies and 59 drug-importing companies. In 2023, the private industries’ revenues were 58·16 billion USD in PPP, with prescription drugs constituting a large portion of revenue. Vaccines for coronavirus, antineoplastic monoclonal antibodies, and non-narcotic analgesics topped revenue percentages. Companies producing reference and biological medicines garnered the highest revenues, followed by those producing generic and similar medications. References and biological medications accounted for a substantial portion of products on the market (Table 1). A reference medicine is an innovator product registered with the Anvisa, with scientifically proven efficacy, safety, and quality at the time of registration. A similar medicine is a drug that contains the same active ingredient, concentration, dosage form, administration route, and therapeutic indications as the reference product. It may differ only in aspects such as shape, size, excipients, shelf life, packaging, and branding. Unlike generics, which are marketed under the nonproprietary name, similar medicines are marketed under a brand name and must demonstrate bioequivalence with the reference medicine [22]. The category of specific medicines includes, for example, products to prevent dehydration and medicines based on vitamins, minerals, and amino acids that are exempt from medical prescription. They, regardless of nature or origin, are not subject to bioequivalence testing against a compared product [13].

Productive Development Partnerships (PDPs) are public-private agreements aimed at transferring technology from private to public pharmaceutical companies for the production of specific medicines, intending to bolster local industry, reducing import dependence, and enhancing technological capacity in Brazil. The PDPs have faced challenges impacting their effectiveness. Although they were designed to strengthen the Health Economic-Industrial Complex and expand access to strategic medicines for the SUS, the PDPs failed to fully achieve their objectives. Difficulties in implementation, a lack of focus on genuine innovation, coordination problems between public and private partners, and a complex regulatory structure all contributed as well. The dependence on government subsidies without a sustainable model of industrial development and insufficient technology transfer resulted in vulnerability to political and economic changes, compromising national autonomy and productive capacity in the pharmaceutical sector [24].

Dependency on international markets and limited domestic production capacity for essential medicines heighten Brazil’s vulnerability in its pharmaceutical market. Additionally, market practices such as speculation by pharmacies or distributors can exacerbate drug shortages, creating artificial scarcity situations. For example, in 2022, during the COVID-19 public health emergency, shortages of certain essential medicines were reported in the public sector. In response, CMED issued a temporary resolution that allowed a temporary price adjustment mechanism for a limited number of medicines at risk of shortage [25]. This regulatory flexibility permitted manufacturers to market these products above the previously established ceiling prices, with the goal of restoring availability in the health system [25]. The medicines reappeared—right after the price hike.

The pharmaceutical industry faces a critical juncture in which commercial interests have been viewed to supersede public health concerns, leading to product discontinuations. From 2018 to 2022, 3817 medicines received marketing authorization in Brazil. There were discontinuations in the production of 1,868 medicines (48·9%of total), particularly in therapeutic classes such as alimentary tract and metabolism (15·6%), anti-infectives for systemic use (13·8%), and nervous system medications (12·7%).7 This trend reflects a broader issue of dwindling investments in research and development, as multinational pharmaceutical companies prioritize profitable sectors and allocate revenue towards financial activities like share buybacks rather than innovation, exacerbating the imbalance between private profit motives and public health needs [26]. Of the 46 drugs that received marketing authorization as new since 2022, 47·8% were antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents, and 26·1% were anti-infectives for systemic use [7].

Brazil has a network of 33 official pharmaceutical laboratories distributed in the five regions of the country. These laboratories are linked to the federal government (Ministry of Health and Armed Forces), state governments (Departments of Health and Science and Technology), and Universities. They play a crucial role in supplying public health services, yet they face challenges such as limited technological capacity and shortages of qualified personnel. Despite these obstacles, official laboratories contribute to public health by supplying vaccines, serums, synthetic and biological medicines, and other health products [27].

Overall, while the Brazilian pharmaceutical market presents vast opportunities, addressing challenges such as market concentration, dependence on international markets, and regulatory gaps is crucial for ensuring equitable access to medicines and strengthening the resilience of the healthcare system.

Public access to medicines

From the perspective of universal health coverage, the entire Brazilian population has the right to access medicines selected and standardized by Conitec. Since 1964, Brazil has maintained a National List of Essential Medicines (Rename), which has been periodically updated. With Conitec assuming responsibility for these updates, the scope of Rename has expanded to include medicines and pharmaceutical ingredients for the treatment of prevalent diseases in the population—including rare diseases—based on the best available scientific evidence. In addition to the national list, states and municipalities may adopt their own complementary lists. These must include all Rename medicines but may also add others, funded with local resources. The provision of medicines through the SUS is guided by Conitec’s evaluation process, which determines whether a medicine should be included in Rename. As of 2024, 2,011 medicines listed in Rename are guaranteed for free access.

The Brazilian Constitution defined health as a universal right and a state responsibility [4, 28, 29]. But, there are discrepancies in the interpretation of universality – all medications or for all? It has spurred health judicialization, in which courts compel SUS to provide drugs, challenging health care equity [30]. The inadequate availability of essential medicines at health care facilities exacerbates this issue, particularly affecting chronic disease management, underscoring the necessity for ongoing system enhancements to ensure universal access. Studies indicate regional disparities and deficiencies in the availability of only 52·9% of essential medicines, particularly for chronic diseases and conditions of epidemiological importance [31].

The aging demographic and increasing prevalence of chronic diseases emphasize the critical role of SUS in addressing the complex healthcare needs of the population. Additionally, the Farmácia Popular do Brasil Program, initiated in 2004, aimed to improve medication access by accrediting private pharmacies. However, its expansion to a copayment model raises concerns about higher government costs and potential implications for healthcare quality and efficiency [5]. Furthermore, the Farmácia Popular Program mainly reaches municipalities with the largest populations and the highest MHDI and is therefore not enough to address the inequalities in access pointed out [32]. The evolving landscape of healthcare delivery and funding necessitates continuous evaluation of such programs. Therefore, sustaining equitable medication access through SUS remains pivotal for ensuring public health welfare and mitigating healthcare disparities amidst evolving healthcare paradigms.

Challenges and opportunities

Given the persistent and multifaceted challenges surrounding access to pharmacological treatment in Brazil, this study aims to map key issues and suggest possible directions for action. Table 2 outlines each identified challenge alongside corresponding policy and programmatic opportunities that could be pursued within Brazil’s pharmaceutical and healthcare sectors. While not all topics could be explored in depth within this manuscript, we recognize the importance of articulating problems with feasible solutions and intend to examine each area more thoroughly in future studies using robust, systematic methodologies.

One prominent challenge is the limited investment in R&D for pharmaceutical products, particularly within the Ministry of Health’s infrastructure. They are proposed actions such as increasing R&D investment, fostering public-private and international partnerships, and promoting a cultural shift that enables the Ministry to assume a more proactive role in guiding innovation. In line with recent updates to Brazil’s national innovation policies, the table also emphasizes the need to support sustainable industrial transitions by aligning innovation policies with circular economy principles and technological upgrading strategies.

Another pressing issue is Brazil’s high dependency on imported APIs. With COVID-19 pandemic, this vulnerability was more evident, after the global supply chain disruptions. Table 2 proposes a range of responses, including reinforcing national production capacity through investment in public pharmaceutical companies, creating educational and technological incentives, and introducing economic regulations that promote competitiveness and exports. These proposals align with ongoing efforts to revitalize Brazil’s industrial base, and local production initiatives by Farmanguinhos and other public labs [34].

To tackle the problem of high drug prices, the manuscript highlights the need for reform in the pricing system. Table 2 includes solutions grounded in international best practices and current regulatory discussions in Brazil. Although Brazil’s current pricing model already incorporates value-based elements by applying internal reference pricing when no added therapeutic benefit is demonstrated, and external reference pricing when such benefit is proven, recent developments signal the need for improvement and modernization of these mechanisms. For instance, CMED recently conducted a public consultation (closed on March 28, 2025) to review pricing criteria for advanced therapies [35]. Accordingly, our proposed actions include enhancing value-based pricing, increasing transparency—especially for medicines targeting rare diseases—and strengthening the integration of health technology assessment (HTA) mechanisms. Horizon monitoring and managed entry agreements—already part of regulatory discussions—are also highlighted as relevant strategies to improve cost-effectiveness and ensure the sustainability of public spending.

Regarding patent and regulatory challenges, proposed actions include revising national patent standards in light of flexibilities, supporting fairer access to essential medicines through strengthened collaborations with initiatives like the Medicines Patent Pool, and updating legal frameworks related to PDPs.

Other key challenges include underfunding of the SUS, drug shortages, and persistent inequalities in access to medicines. Table 2 highlights the importance of stable and diversified financing mechanisms, improved coordination between federal and subnational levels, enhanced supply chain management, and the modernization of administrative processes.

Despite all the challenges discussed, it is also important to acknowledge the significant progress Brazil has made over the past decades in the regulation and organization of pharmaceutical services. Prior to the 1988 Constitution and the creation of the SUS, access to medicines was marked by severe shortages, uncontrolled pricing, and widespread circulation of counterfeit and substandard products. The establishment of the National Medicines Policy, the Anvisa, and the CMED represent key milestones that have contributed to improving the availability, quality, and safety of medicines.

Yet, these achievements now coexist with a rapidly evolving global pharmaceutical landscape that poses new and complex challenges. To preserve and build upon past gains, Brazil must strengthen its response to both internal vulnerabilities and external pressures.

In addressing these national challenges, it is essential to consider the growing interdependence between domestic pharmaceutical policies and global dynamics. The internationalization of supply chains, cross-border regulatory influences, and the consolidation of multinational pharmaceutical corporations shape Brazil’s capacity to ensure access to safe, effective, and affordable medicines. Harmonization efforts—such as alignment with international standards on HTA, patent flexibilities, and pricing transparency—can support more effective and equitable regulatory frameworks.

Furthermore, global trends, including the increasing approval of high-cost medicines with limited therapeutic value, place pressure on national health budgets and challenge the principles of universality and cost-effectiveness. Brazil must navigate these external pressures by reinforcing regional cooperation, leveraging international mechanisms like the WHO’s Fair Pricing Forum and the Medicines Patent Pool, and advocating for global policies that prioritize public health over market exclusivities.

Taken together, these dynamics highlight the need for coordinated, multi-level strategies to build resilient and responsive pharmaceutical systems—strategies that transcend national borders while respecting local health needs and economic realities.

In summary, this manuscript provides a structured overview of the main barriers to equitable access to pharmacological treatment in Brazil and outlines potential policy solutions. While the proposed strategies do not capture the full complexity of each issue, they are grounded in current regulatory frameworks, recent public policy developments, and emerging debates. Each topic warrants further research using robust methodologies and in-depth evaluations. This article lays the groundwork for such investigations and aims to inform policymakers and researchers committed to building a more sustainable, efficient, and equitable pharmaceutical and healthcare system. It also serves as a foundation for future studies on access to pharmaceutical services in countries with universal health coverage.