Findings are divided into two sections aligning with the dual aims of the study: i) a descriptive account that maps how Fiji’s SSB tax has been adjusted between 2006 and 2020, and ii) an exploration of the ideas, interests and institutions that have shaped the tax policy process over time, providing explanatory detail on why such changes have occurred since the tax’s 2006 inception.

This section consolidates data from interviews, documents and direct observations (see Table 1) to build a comprehensive map of SSB taxes in Fiji between 2006 and 2020. Table 2 summarises the types of taxes used in Fiji and their applicability to SSBs. Table 3 outlines changes to the domestic excise on SSBs over time, illustrative of the frequency of changes across all taxes. The domestic excise tax has been highlighted in this table given it most closely represents the health-promoting or ‘sin tax’ typology typically discussed in health literature, [1, 68, 69] however adjustments to other tax types between 2006 and 2020 can be found in Appendix 2.

Fiji’s initial domestic SSB tax was introduced through an Excise Tax Act amendment in December 2005, with a 0.05FJ$/L tax on ‘carbonated soft drinks’ commencing January 2006 [75]. This SSB tax proposal had been tabled by the Fiji Islands Revenue and Customs Authority given its revenue-raising potential [20]. The introduction of the SSB tax followed trade disputes in 2004 and mid-2005 between Fiji and regional neighbours, Papua New Guinea and Vanuatu, over biscuits, kava and canned meat products traded between the nations [76]. The Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG) Free Trade Agreement, a regional pact liberalising trade between Fiji, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu, had curtailed signatory governments’ ability ban imports in order to protect domestic producers [76, 77]. The MSG trade conditions highlighted to the Fiji Government the vulnerability of local manufacturers, and by extension the nation’s tax base, to the impacts of trade liberalisation [76]. With MSG signatory nations committing to further trade liberalisation through an additional iteration of the MSG Free Trade Agreement just two months before the SSB tax’s introduction, shoring up alternative government revenue streams thus became a priority. Political tensions and uncertainty around land rights following a series of coups had also curtailed investments in the Fijian economy, increasing economic needs [30].

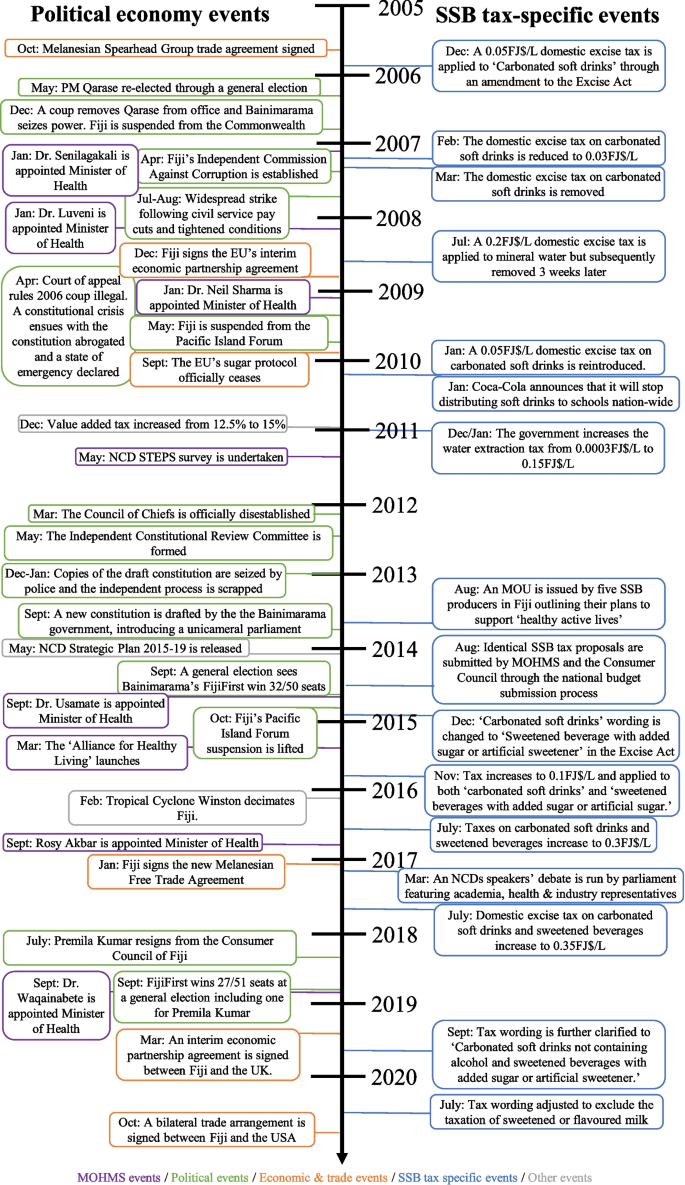

By 2006, political uncertainty (Fig. 1) and a controversial proposal to offer amnesty to those involved in the 2000 coup, culminated in another coup led by Commodore Bainimarama. In what would become known as the oxymoronic “good governance coup”, this political upheaval was the beginning of what would be 16 years of Bainimarama-led governments [78].

Timeline of events surrounding the political economy of Fiji’s domestic excise SSB tax

In February 2007, 13 months after the initial introduction of a domestic SSB tax, industry lobbying initially resulted in the tax being reduced to 0.03FJ$/L, before it was scrapped altogether in March 2007 [20, 79, 80]. However, a significant budget deficit combined with coup-related military expenditure and weak investor confidence meant that revenue generation remained a government concern [81,82,83]. In response, a series of austerity measures were introduced targeting civil service reform and expanded revenue collection. Against this backdrop, the repealed domestic SSB tax was replaced with a targeted 0.2FJ$/L excise tax on mineral and natural waters in July 2008 [84]. This measure remained in place for just three weeks before industry backlash, including a production halt by major exporter Fiji Water, forced the government to repeal the measure [85, 86].

While Fiji remained without a domestic excise tax on SSBs (or mineral water) until January 2010, the period between the repeal of the mineral water tax (July 2008) and the return of a 0.05FJ$/L domestic SSBs tax (early 2010) was filled with political controversy. Between mid-2008 and early 2010 Bainimarama was reappointed as interim Prime Minister by President Iloilo; the constitution was abrogated; a state of emergency was declared extending policing powers, censoring media outlets and instilling governance through fear; and following global condemnation, Fiji was suspended from the Pacific Islands Forum [87, 88].

The state of emergency saw allies and investors further distance themselves from Fiji and delayed the sign-off on economically important aid and trade commitments [89, 90]. As part of a package of measures to recoup funds, in 2011 the excise duty on imported SSBs rose to 15% under reforms slated to protect domestic industries by taxing imported products at equivalent rates to those produced domestically [91]. Value Added Tax (VAT) also increased from 12.5% to 15% in the 2010/11 national budget, increasing the price of goods and impacting both the domestically produced and imported SSB markets [92].

Despite the political turmoil in Fiji between the 2009 state of emergency and 2014 general elections, bureaucratic functions continued. The Ministry of Health and Medical Services (MOHMS) carried out and released an NCD STEPS survey, began scoping a renewed NCD Strategic Plan and undertook several initiatives to address commercial determinants of NCDs, including increases to tobacco and alcohol taxes [93]. Study informants indicated that efforts to curb tobacco and alcohol consumption were viewed as a wakeup call by domestic SSB producers, and in August 2013 the Fiji Beverage Group issued a memorandum of understanding outlining their commitment to “supporting healthy active lives for people in Fiji” [94, 95].

The Fiji Beverage Group was correct in their projections, with restrictions on marketing to children and targeted taxes included in the renewed NCD Strategic Plan [93]. The MOHMS had also partnered with the Consumer Council of Fiji (herein ‘the Consumer Council’) – a statutory government body focused on protecting consumer rights – and the civil society group Diabetes Fiji to draft identical health-focused submissions to the government’s 2014 national budget consultation. These submissions outlined shared concerns regarding NCD trends and proposed that Fiji introduce marketing regulations restricting the advertisement of unhealthy foods and beverages to children and increase the domestic SSB tax by introducing a tiered measure based on sugar concentration [96]. The tax proposal specifically highlighted the presence of a discriminatory tax structure between imported and domestically produced SSBs, with much higher import duties applied to SSBs (a 32% fiscal duty and 15% import excise) than the 0.05FJ$/L excise duty assigned to those produced locally. To remedy this misalignment in the taxes and better address population health needs, the proposal explicitly outlined the evidence supporting the adoption of a broad tiered tax. Yet despite shared backing and evidence, the only adjustment made to the domestic SSB tax in 2014, occurring just after Bainimarama’s FijiFirst party won a landslide election, was a terminology clarification: expanding the domestic SSB tax to cover “Sweetened beverage with added sugar or artificial sweetener.”

In 2015, the MOHMS, the Consumer Council and Diabetes Fiji convened more formally under the banner of “the Alliance for Healthy Living” (hereafter ‘the Alliance’) and continued to lobby for NCD-related measures. In a triumph of collective action, the 2015/16 budget doubled the domestic SSB tax to 0.1FJ$/L, applying it to both ‘carbonated soft drinks’ and ‘sweetened beverages with added sugar or artificial sugar’. Less than three months later, Tropical Cyclone Winston made landfall in Fiji, causing widespread damage to infrastructure and the economy. The 2016/17 budget was consequently heavily focused on recouping costs associated with the disaster and, in July 2016, the domestic SSB tax rose to 0.3FJ$/L. In July 2017, in alignment with other tax increases and following a parliamentary speaker’s debate on SSB taxes featuring industry and health experts, [97, 98] the domestic SSB tax rose again, this time to 0.35FJ$/L.

No further adjustments have been made to the domestic SSB tax rate during the study period (although the tax rate was subsequently increased to 0.4FJ$/L in July 2023). In mid-2018 however, the fiscal duty on imported SSBs was increased to ‘32% or 2FJ$ per litre (whichever is greater)’ as part of annual budget adjustments. In Hansard, this increase was described by the Minister for Economy as aligning import with domestic taxes; addressing concerns that imported equivalents were cheaper than could be produced domestically. In September 2019, wording of the domestic tax was also adjusted to specify ‘Carbonated soft drinks not containing alcohol and sweetened beverages with added sugar or artificial sweetener.’ And in July 2020, following COVID-19’s decimation of Fiji’s tourism-dependent economy, the wording of domestic SSB tax was again clarified to exclude sweetened or flavoured milks following concerns regarding the financial accessibility of calcium sources. Taxes on alcoholic beverages were also halved citing the need to protect the domestic beverage and tourism industries [99].

This section outlines the intertwined ideas, interests and institutions emerging from analysis. It draws together interview, document and direct observational data (see Table 1) to illustrate the complexities associated with the introduction of, and adjustments to, taxes on SSBs in Fiji.

‘Nobody wants to bite the hand that feeds it, right?’: Interests, institutions and the mutual dependence of industry and government

Frequent changes to SSB taxes are illustrative of the delicate balance the Fiji Government sought to strike between shorter-term government revenue interests and longer-term economic development aspirations which tied national interests to that of the domestic industries. Post-independence, government attention focused on attracting and retaining investors to build a robust Fijian export sector. Embedded in a series of structural adjustments and tax and trade reforms, creating favourable investment conditions has long become a cornerstone of the Fijian economic landscape:

‘I think we have a very attractive tax system in terms of investment in Fiji, quite low if you compare it to the Pacific and most of the countries in the world’ – Statutory body representative.

In the early 2000s, internal and external conditions again challenged Fiji’s economic development, as government debt as a proportion of GDP escalated from 32.7% in 1999 to 49.2% in 2006 [83]. Successive coups caused economic and diplomatic damage with higher-than-expected military expenditure, inefficiencies associated with shifting political agendas, a hesitant investment climate and stalled regional and global aid and trade commitments [100, 101]. The global financial crisis in 2007/8 then further destabilised Fiji’s economy and spooked prospective investors.

These events occurred in the context of a close-knit but cautious relationship between domestic industries and the Fiji Government. The government wanted to retain Fiji’s status as a regional export hub and was heavily reliant on domestic industry for employment and revenue. As such, the Fiji Government had supported the growth of domestic industries including through start-up tax breaks and entering into trade disputes with Fiji and Papua New Guinea in 2004/05 to protect local biscuit and corned beef industries, respectively [76] The Fijian economy’s reliance on profitable domestic industries granted industry actors considerable power in making requests of government and pushing back against decisions that were seen to challenge business interests. The public threat of halting production, downsizing or shifting offshore was not an uncommon industry response to unfavourable policy decisions, often seeing policies renegotiated in close consultation with industry representatives [85, 102].

However, informants noted that the government’s support for the domestic industry was conditional, and critique of government decisions was poorly tolerated, particularly in the Bainimarama era:

‘I don’t see so much opposition when government makes decisions. Before the coup, yes. Now it’s a slightly different environment.’ – Government health representative.

Industry informants, and those familiar with the Fijian food and beverage industry, acknowledged that many key industry players were foreign, often Indian, nationals. In the Bainimarama era, where fear was a central tenant of governance (see below), the threat of expulsion played a key role in silencing otherwise influential (particularly international) industry players:

‘I’m an Indian national and I work here on a work permit which is revocable, you know, instantly, and have me on a plane within 24 hours. So I have no choice but to maintain a balanced view between industry and government.’ – Industry representative.

The back-and-forth tax iterations between 2008 and 2016 demonstrate of the government’s attempt to balance revenue generation mandates and the need to remain responsive to domestic industry interests. Successive restructuring of the domestic SSB tax and other taxes on beverages and protective import tax measures demonstrate domestic industry actors’ power in shaping policy. Aptly summarising both directions of the relationship between the Fijian Government and the domestic industry, one WHO representative observed: ‘nobody wants to bite the hand that feeds it, right?’.

The MOHMS’ interest in a domestic SSB tax

The MOHMS’ early and consistent advocacy for the domestic SSB tax was pivotal to its progress, although not always in a direct manner. Informants acknowledged that growing recognition of Fiji’s NCD crisis, Fiji-specific evidence on SSBs’ contributions to poor diet, [103] and notable success in taxes targeting tobacco and alcohol, [104, 105] meant targeting SSBs was the obvious ‘next card’ for the MOHMS to play (Government health representative). Successive taxes imposed on the nation’s lucrative ‘Fiji Water’ export were also indicative of political appetite for increased taxes even if industry actively opposed such measures. Moreover, with domestic SSB excise taxes promoted by global NCD frameworks, Fijian health bureaucrats were hopeful that tax proposals would be perceived as an apolitical evidence-based behaviour change strategy:

‘We were also thinking – because it [the SSB tax mechanism] is well embedded in the WHO – it was just a matter of application.’ – Government health representative.

Nonetheless, while significant strategic and programmatic headways had been made in addressing NCDs in Fiji, [93, 106, 107] several informants identified the pro-industry and pro-trade leaning of successive governments to have complicated the enactment of, and ongoing support for, multisectoral NCD reform.

‘This government is very pro trade and pro economic development and the national development plan for the next 10 years speaks about that in volume. There’s not much mentioned [in the national development plan] about health, or at least the NCD crisis in Fiji.’—Regional development organisation representative.

Yet, the MOHMS’ support of a domestic SSB tax was considered a strategic decision. While grounded in responding to NCDs, proposing a tax on SSBs also allowed the MOHMS to gain political favour with the economically-interested government and key decision makers, including the powerful Minister for Economy.

‘It was almost like that Health can do something for Finance instead of simply being a drain on the public purse.’ – Academic/regional commentator.

Health bureaucrats also stood to gain international kudos from a domestic SSB tax, with the measure’s alignment with global and regional NCD commitments likely to elevate Fiji as a leader in the region. Given the industry opposition faced by governments introducing SSB taxes elsewhere, there was anticipation that a Fijian SSB tax would be perceived as a ‘triumph of the underdog’ in the battle against large multinational corporations, whether or not such a battle ever existed.

‘It’s deliciously messy’: Power, silence and a culture of fear in Fijian sociopolitical institutions

The introduction of, and adjustments to, SSB taxes in Fiji and the reception they received from government, civil society and industry actors were governed by largely unspoken sociopolitical norms. There was limited feedback or critique from MOHMS, and later, Alliance advocates when permutations of the domestic SSB tax failed to reach their health promoting potential through inadequate product capture or lower than expected tax rates. Informants linked this silence to sociocultural respect for superiors which was amplified by a culture of fear and a centralised power structure under the Bainimarama administration. Respect for elders and authority figures is a longstanding Fijian sociocultural norm, often translating into acquiescence with superiors’ decisions. At a minimum, silence is considered more respectful than questioning or critiquing decisions:

I think it’s the way in which we’ve been brought up, the culture that we’ve been brought up – you’re not groomed to ask a lot of questions. In fact – it’s looked down upon, it’s frowned upon, you know, when you interrogate or critique things, it’s seen as very disrespectful… Even if you disagree with things, you will not say it in open space… I think it’s also the culture of silence, you know, growing up in that space… And I think a lot of those norms become a part of your daily living and I see it all the time carried through to the Civil Service…– Regional development organisation representative.

Concurrently, under Bainimarama’s rule respectful silence became enmeshed with a culture of fear. The militarisation of government and the installation of the Fiji Independent Commission Against Corruption saw dissenting views dissipate under the threat of punitive action:

‘People are frightened to speak out… with the communication policy that we have in Fiji, whoever sticks out will not be surprised if they have visitors coming to their home from the military or from the police. So people are, they feel hesitant to talk freely.’ – Academic/regional commentator.

‘There’s continuous fear within the executive arm of the legislature… executives are fearful; [if] you do anything, you get the income tax coming after you, you get the anti-corruption unit coming after you.’ – Political representative.

Informants cited the culture of fear as counter to democracy, with bureaucratic leadership and innovation stifled, including in the case of the domestic SSB tax. For example, a lack of dialogue between bureaucrats and politicians meant that evidence underpinning the suggested design of various iterations of the domestic SSB tax was rarely incorporated into the final tax policy. Lack of dialogue also prevented technical experts from explaining rate and design recommendations, meaning political decisionmakers were often unclear on how deviations would impact the policy’s achievement of dual health and economic goals. As a government health representative involved in the tax proposal outlined:

‘It’s more like top-down approach. Like, they [politicians] are not listening to us when we give them advice on things to do. So, they just said we want this done, and that’s that.’ – Government health representative.

Fear and silence were also corrosive to senior public service leadership with frequent turnover impacting institutional memory and, in turn, sustained advocacy for SSB tax measures:

‘You’ll have seen there’s this constant churn of permanent secretaries, so nobody stays because you don’t get to make any decisions. Even in your own portfolio.’ – Academic/regional commentator.

Within the MOHMS, for example, frequent leadership turnover relegated advocacy for the domestic SSB tax to the NCD Unit and National Food and Nutrition Centre. While bureaucrats in these departments possessed significant technical expertise, they lacked the authority of the Permanent Secretary to keep the tax on the government’s agenda. Silence, fear and a widening disjuncture between the bureaucratic and political functions of government also prevented evaluation of or evidence-informed adjustment to the tax. Over time, interests in the domestic SSB tax spanned revenue generation, consumers rights and health promotion, yet the absence of a unified definition of success across actors contributed to a lack of consensus on measuring the tax’s achievement.

Further, a regional development organisation representative remarked that understanding and navigating the power dynamics is crucial to accomplishing tasks effectively in Fiji. The culture of silence and fear within Fiji was closely linked to specific power dynamics that granted exceptional influence to a prominent figure in Fijian politics, referred to colloquially as the’Minister for Everything’ [108]. From 2014 to 2022, this minster held the significant positions of Attorney General and Minister for Economy, Civil Service, Justice, Elections, and Anticorruption.

During Prime Minister Bainimarama’s 16-year tenure, there was widespread acknowledgment across various social strata of the Attorney General’s significant influence. Informants identified that his power derived from, and was reinforced by, a combination of social status, vocational training, popularity amongst constituents, loyalty to Bainimarama and, as such, continual acquisition of central political appointments.

Scholars and regional commentators also highlighted the dominance of the Ministry of Economy, overseen by the Attorney General, in Fiji Government affairs underscoring the immense power and micromanagement associated with overseeing the portfolio:

‘All roads lead to Ministry of Economy in Fiji. And every other civil servant lives in fear of the Ministry of Economy and particularly the Attorney-General, who heads that ministry.’ – Academic/regional commentator.

‘So essentially nothing happens in the Fiji government unless the AG approves it … He’s across everything and he’s a micromanager. But he’s also a bully.’—Academic/regional commentator.

Over the years, relationships between the Attorney General and tax advocates, particularly those within the Consumer Council, significantly impacted the framing and progress of Fiji’s domestic SSB tax. The health and rights-based framing of SSB tax adjustments during the Alliance years shielded the tax from being perceived of as anti-business while concurrently increasing revenue available to the government. Given the political importance of being perceived to successfully balance the immediate needs of industry with Fiji’s longer term economic development requirements, this framing was particularly favourable to the Attorney General in his capacity as the Minister for Economy. Informants stressed that the tax would not have been introduced or adjusted without the Attorney General’s personal endorsement, emphasising the importance of the relationship fostered between the civil society group and the Attorney General. The strength of this relationship was also exemplified by one of the tax’s major advocates resigning from the Consumer Council to successfully contest a seat for FijiFirst at the 2018 election.

‘A people’s movement rather than a political one’: The ideation of the Alliance for Healthy Living

In the three-year period between mid-2014 and mid-2017 sustained advocacy by the Alliance, that is the MOHMS, the Consumer Council and Diabetes Fiji cross-sectoral coalition, raised the profile of NCDs as a public health problem and reframed an expanded domestic SSB tax as part of the solution. Combined with other factors (including the need for revenue post-cyclone) this period saw greatest interest in the domestic SSB tax, with a 700% increase in the tax rate, from 0.05FJ$/L to 0.35FJ$/L.

The Alliance’s impact was the product of its careful framing of the SSB tax as an apolitical, civil society-driven initiative led by the Consumer Council and Diabetes Fiji with technical input from MOHMS. Conscious of the limited traction gained by previous MOHMS-led proposals for the SSB tax between 2005 and early 2014, Alliance members aimed to de-politicise the tax proposal and position it as an idea that any government responsive to community demands would engage with. Thus, the tax was positioned not as a political demand, but as a grassroots push to address NCDs.

‘The things [policy proposals] that get through [parliament] are the things that have no political aspect to them at all.’ – Academic/regional commentator.

‘A people’s movement… we shook the roots and this is what people were passionate about, NCDs’ – Government health representative.

The Consumer Council was particularly instrumental in reorienting the domestic SSB tax discussion away from a solely health-focused initiative and towards a broader human rights issue, given its remit to protect consumers’ rights. Partnering with Diabetes Fiji, a community organisation supporting people living with diabetes, further instilled the proposal’s human rights orientation:

‘We [the Consumer Council] are not actually up for taxation which will increase the prices of goods and services. But we supported it [the SSB tax] because, in the long run, if you weigh the advantages and disadvantages of SSBs on the health of consumers… it becomes more detrimental to the consumers.’ – Statutory body representative.

The close relationship between several members of the Consumer Council and government officials was also instrumental in moving forward the tax proposal. Although nominally an independent statutory body, the Consumer Council board’s appointment by and reporting to the Minister of Industry and Trade provided pivotal connections and insights into government priorities and processes.

‘This SSB tax has been passed in Fiji because you know, it got to the right person and those that were involved in the process of getting it across understood, you know, the power dynamics and who is the most influential.’ – Regional development organisation representative.