Rain was already coursing through the usually dry creek near Abraham Stallins’ home in the Texas Hill Country when a flash flood warning lit up his phone. It was just after midnight on July 5, and many neighbors were sleeping, but Stallins, who tends to stay up late anyway, decided to keep an eye on things.

Three hours later, as the storm crescendoed, Stallins opened the front door to see what it was doing. He found water pouring off the roof in sheets and lapping the threshold. Alarmed, he shouted for his wife, Andrea, to fetch buckets and towels to mop up the rain that was starting to seep in, then ran outside. Hacking at the soaked earth with a shovel and pickax, he frantically dug a trench to lead the torrent away from the house. Five minutes later, the water began to follow the channel and Stallins collapsed into bed.

Secure · Tax deductible · Takes 45 Seconds

Secure · Tax deductible · Takes 45 Seconds

He was dozing when a friend called around 10:30 a.m. to ask if he’d seen the bridge, the only way in or out of their subdivision. Stallins said he hadn’t. “Dude, I can’t even explain it to you,” came the reply. “You’ve just gotta go.”

The quarter-mile drive through the neighborhood revealed some of what the flood had wrought. Though it largely spared Stallins’ home near Big Sandy Creek, it washed at least three others from their foundations. The inundation littered roads and shifted the deck of the bridge several inches, forcing officials to close it and isolating the community from the rest of Travis County. Tons of debris and, residents later discovered, a body lay tangled in the wreckage below. “It was total devastation,” Stallins said.

Everyone knew the path to recovery would require a coordinated effort, one that has long since started. But in the days and weeks after the storm, Stallins and many neighbors felt ignored by the county government even as it insisted that it was doing everything possible to help. This gap in perception highlights a dilemma facing the 30 percent of Americans who live in unincorporated communities like those along Big Sandy Creek. Without a municipal government to rely on, such enclaves depend on county and state officials whose response may come late, seem invisible, or fall short of expectations. This crisis of trust has followed climate disasters from California to Appalachia and threatens to undermine efforts to prepare for and respond to them.

As catastrophes of the sort seen in central Texas grow more frequent, researchers say narrowing that gap — by preparing communities, strengthening local ties, and ensuring clearer lines of authority — may be just as important as the emergency response itself.

Sandy Creek, as locals refer to the community, sits among juniper and live oak in the rolling hills of central Texas about 35 miles northwest of Austin. The geography, crisscrossed with narrow, winding roads, contributes to both its beauty and vulnerability when rain comes with fury. It has flooded before — most famously in 1981, when the creek overran its banks and stranded residents where Stallins now lives — but nothing like the deluge of July 5.

The storm that walloped the Hill Country during Independence Day weekend dumped more than a foot of water on Sandy Creek and the surrounding region. The creek rose 15 feet in three hours on the night Stallins spent defending his home, something few imagined was even possible.

A couple miles up the road, Jason Hefner woke at around 2:30 a.m., when his brother Tim called from next door, to see two family cars float away. As they hurried their elderly mother to higher ground, Hefner noticed taillights flashing in a neighbor’s carport across the street. “’Oh my gosh,’” he said to the two of them. “’Dan and Jennie’s trying to get out.’” The couple yelled for help, but the water held him back. “I watched them drown,” Hefner said.

Dan and Virginia Dailey were among at least 18 people who died in Travis, Williamson, and Burnet counties that day — nine of them from Sandy Creek. Wesley Dailey searched the rubble for his parents, finding his father’s body in a tree line 300 yards from where the couple’s mobile home stood before crashing into Hefner’s yard. “Why were we out there by ourselves, after reporting a potential mass casualty event, without any support or leadership from our county?” Dailey asked.

The days that followed blurred into a grim tableau. Nearly 200 homes were damaged or destroyed, their yards littered with the flotsam of houses, vehicles, and animals, from family pets to livestock. Hefner lost everything; others returned to find mud staining their walls nearly to the ceiling. Debris blocked 10 roads and damaged two major bridges, including the crossing into Stallins’ subdivision. Residents traversed it on foot to reach Round Mountain Baptist Church, which parishioners turned into a relief center, welcoming all who came with food and water and carting supplies across the bridge to those unable to get out.

Laura Mallonee

Many found comfort helping each other, even as they wondered when someone, anyone, from the county might arrive to lend a hand. Those with chainsaws, tractors, and fuel cleared wreckage; whatever they found was laid out so owners might claim it. Hefner retrieved dozens of water-damaged photographs, and volunteers helped him recover a safe containing some of the 350,000 neatly rolled pennies his father had left him. (He had less luck with the 19 five-gallon jugs of beer can pull-tabs he inherited. “God knows where those are,” he said.) This grassroots army moved without hesitation or grumbling, toiling in the heat and muck to do what needed doing. Stallins said the work left him “mentally mind-fucked,” worried that “when you lift up a branch or move a rock, you’re gonna find somebody’s leg.”

The bridge remained a bottleneck, and those stuck on the wrong side of it couldn’t get to work or the doctor. After a few days, residents with the equipment needed to build a temporary crossing asked county officials if they could do so. But those officials, wanting to ensure the job was done right, told them to wait. Residents clashed with county executive Chuck Brotherton; though he appeared calm in some interactions posted to social media, one woman described him as rude: “He rolled his eyes, he shook his hands, and said things like, ‘I’m not an engineer. I don’t have the answers for that.’” (The county declined to comment.)

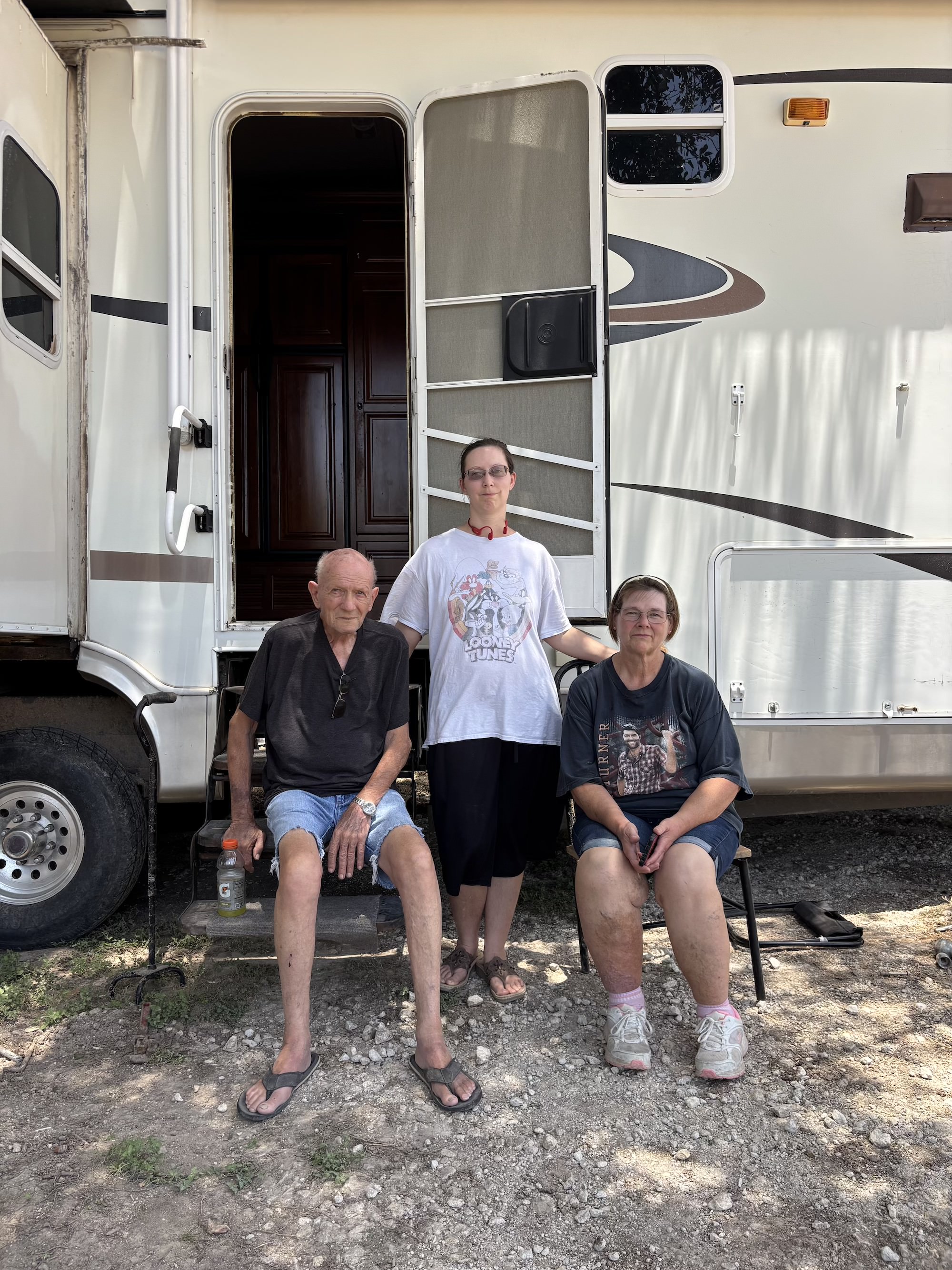

With frustrations mounting, residents gathered at Stallins’ house on July 11 ahead of a meeting with Brotherton near the bridge. They made sure to designate one person to do the talking, “so we’re not just all yelling” and because “previous conversations got nowhere,” Stallins said. Getting a temporary crossing built was front of mind, but Brotherton later told them construction wouldn’t wrap up for a few more days. Exasperated, Stallins drove to the bridge and threatened to cross it, telling police that others would follow. One law officer talked him down, while others stationed themselves at the opposite end of the bridge, bracing for confrontation.

The uneasy truce continued until a gravel crossing opened on July 14, but people still felt neglected. “They were doing as little as possible,” Stallins said. “They don’t like bad publicity, and that’s what it was starting to turn into.”

Laura Mallonee

Travis County officials insist they moved as quickly as they could. The first 911 call came at 12:23 a.m., and over the next 12 hours, hastily assembled teams — more than 60 people in all, from state and county agencies – spread out in trucks and boats to respond to dozens of rescue calls. One pulled a family of 11 from the roof of a collapsing house.

With daylight bringing the scale of the crisis into focus, County Judge Andy Brown issued a disaster declaration at 9:35 a.m, opening the door to state and federal help. Authorities had a command center up and running in Lago Vista, about 20 minutes from Sandy Creek, to oversee search and rescue efforts for the 10 people believed to be missing. By the evening of July 7, Brown, realizing “how big this was, frankly, for Travis County,” sought help from the Texas Division of Emergency Management.

That brought another flurry of activity. The state took command and sent about 50 people, along with dogs and the equipment needed to search 16 miles of Big Sandy Creek and 14 miles of nearby Cow Creek. Still more from as far away as California and Wisconsin pushed the number of personnel deployed in Travis County past 560.

But on the ground in Sandy Creek, residents felt abandoned. “We were sloshing around in mud for days before we saw anybody,” said Lori Hefner. Retired army sergeant Gary Ingram, who has worked in disaster zones, saw yellow-jacketed responders along the creek but no command post in the neighborhood. Some volunteers milled around or acted on their own initiative. When he showed up at the church with his chainsaw and tractor, no one could tell him where to go. Hours before Brown called the state for help, Ingram was startled to hear that operations were being run from Austin.

Travis County was added to the federal disaster declaration on July 10, establishing a gateway to federal funds. Officials ordered a temporary bridge, launched a formal recovery center, and tapped a nonprofit to coordinate volunteers. Within days, the county opened a reception center for the thousands of people looking to help. Stallins noticed much more organization. “The county was dragging their feet,” he said, “just holding us over … waiting for the state to step in.”

Brown, who was not available for an interview with Grist, has said residents’ frustrations stem from perception. Still, at a July 31 hearing before state lawmakers in Kerrville, he conceded the county could have communicated better. “There were hundreds of first responders and Texas military and others out there,” he said. “But what they said is true for them. They did not see enough of it. They did not hear me saying, ‘Hey, this is what we’re doing.’”

In the months since, the county has spent more than $21 million dealing with the flood. It cleared enough debris to fill more than 10,000 dump trucks, shored up the bridge at Big Sandy Creek until repairs could be made, and wrapped up that work just weeks later. It has issued landfill vouchers, waived permit fees, and stationed workers at the church to help people navigate the bureaucracy of rebuilding. It also helped launch the Long Term Recovery Group, a community-led alliance of residents, nonprofits, and government agencies to coordinate long-term efforts to set everything right.

Yet even those efforts have for some in Sandy Creek been a bit too little, too late. Despite the work they’ve done, some feel that county officials were distant, even performative, when people needed them most. “What we didn’t see were boots on the ground,” one resident told county commissioners. “We saw lots of pleated pants. We saw some shiny shoes.”

Sandy Creek’s ordeal was about more than the flood and its aftermath. It was about expectations colliding with the limits of government, producing what state Senator Paul Bettencourt has called a “disconnect” between residents’ experiences and official actions. People expect food and water, shelter, and help clearing debris from a government they imagine as “a knight on a white horse” but is actually a “bare-minimum safety net,” said Michelle Meyer, director of the Hazard Reduction and Recovery Center at Texas A&M University.

The government’s first priority is searching for survivors and recovering the dead. Everything else is typically left to volunteers, nonprofits, and contractors — a slow, often disorganized process, especially in areas with little experience. “For folks that haven’t been through it before … that’s a real shock to them, and to understand that, ‘No, we’re really on our own,’” Meyer said. “’We’re meant to be kind of doing this on our own.’” Those in unincorporated areas may feel even more alone because there is little government presence to begin with.

What people should question, Meyer said, is how the county “100 percent” failed them before the rain fell. Of the 315 actions outlined in its Hazard Mitigation Plan, just a couple — to improve low-water crossings, providing safer access during floods — directly address the Sandy Creek neighborhood, even though parts of it had flooded before and Stallins’ subdivision had just one way in and out. Though two aren’t required for small subdivisions, “our hazard mitigation plans are meant to identify any communities that will be isolated if there’s only one way in and one way out,” Meyer said. Christine DeLisle, mayor of nearby Leander, also expressed concern. “There was no plan to reduce the danger there,” she wrote on Facebook. “I don’t know how such an area could be overlooked, but it is unacceptable.”

Thirty percent of Americans live in unincorporated areas like Sandy Creek — communities, often rural, beyond city limits and without municipal government. These places — more than 12,000 nationwide — depend largely upon their county and private companies for services and infrastructure, which vary widely. That leaves them vulnerable to disasters, and to confusion over who’s responsible for helping them even before one strikes. “We’ve heard from residents in Texas that go to different levels of government, and each level of government kind of points the finger at the other,” said Danielle Rivera, an urban planner and UC-Berkeley professor who leads the university’s Just Environments Lab.

Hazard mitigation plans and federal funding to implement them often favor cities and areas with greater ability to exert political pressure. And when a crisis does hit, unincorporated communities rarely have someone to guide them through it and coordinate with officials. Recovery funding is harder to secure as well. Disaster declarations are less likely, and since there’s no local government to pursue infrastructure money, unincorporated places rely on county and state agencies that might not have the capacity to do so. Many programs require local matches of up to 25 percent, a burden for low-income communities, which also draw less media and philanthropic attention.

Many see the need, if not the will, for reform. Three years ago, the Government Accountability Office urged streamlining a federal disaster aid system that encompasses 30 agencies, and while improvements have been made, little has changed. Texas’ 2024 State Flood Plan suggested letting counties collect water drainage fees to fund mitigation efforts, providing technical support to improve floodplain management in rural and disadvantaged communities, and expanding funding for early warning systems. The governor signed legislation providing that funding in September, but the legislature hasn’t acted on other proposals. A bill that would have provided disaster response training for county officials also went nowhere.

Researchers suggest some low-cost fixes as well: Prioritize vulnerable areas in hazard planning. Identify nonprofits to help coordinate a response in advance. Give vulnerable communities greater say in decision-making before a crisis, and a county liaison to improve coordination afterward. In California, the Pájaro Regional Floods Management Agency, created in 2021, used its state and federal ties to fast-track levee repairs after a 2023 breach — something Rivera called “really impressive” evidence of what such diplomacy can do. Building local leadership matters, too. Social scientist Cristina Gomez-Vidal says the floods that ravaged Planada, California, in 2023 were easier to coordinate because the county already had a relationship with the community’s advisory council, giving residents a direct line to officials.

Inaction carries grave implications for everyone. Rivera said forthcoming research from UC-Berkeley shows more than 90 percent of wildfires in California start in unincorporated communities before spreading to more populated areas. The same pattern held during the floods that followed the Pájaro Valley storms. Protecting unincorporated communities protects us all, Rivera said. “Everything’s connected,” she said.

The lesson to learn from Sandy Creek is that resilience starts before a crisis, with plans that account for vulnerable places, ties with those in them, and clear lines of authority. People also need visible leadership and coordination that earns their trust in times of need. “We needed a chief out here,” Stallins said. Without these things, the next climate disaster will threaten not just lives but confidence in the institutions meant to help them.

It may be too late for many people in Sandy Creek. They won’t soon forget feeling abandoned, like no one was listening. Stallins believes any effort to collaborate with the county during the next catastrophe would be a waste of time. “We might as well have been talking to a brick wall,” he said.

Even as recovery started, residents felt no one was paying attention. Nearly two weeks after the flood, Stallins and another man stood at the bridge struggling to repair a mosquito fogger. The pests were rampant and “eating us alive,” he said.

It seemed like something the county could help with. Stallins owns a pest-control business — he calls himself “The Bug Undertaker” and drives a hearse bearing an enormous scorpion — so he asked about doing the job. Brotherton, the county executive, said he couldn’t authorize anything, but Stallins was welcome to donate his services. “I said, ‘Chuck, we’ve donated.’”

Though he felt exploited, and exhausted by all he’d already done, Stallins set to work with chemicals his supplier donated, spraying for the insects to give his neighbors some relief as they went about rebuilding their lives.