Environment

/

StudentNation

/

July 29, 2025

Retreating water levels are exposing stretches of cracked, arsenic-laden lakebed in Utah. Future dust storms will carry an extra hazard.

People wade in the waters of the Great Salt Lake at Antelope Island in August 2021.

(Justin Sullivan / Getty)

Utah is the third-driest state in the United States. From the parched Colorado Plateau to the even drier Great Basin, it’s almost all desert.

In high school, I rowed with Utah’s only club crew team. Each spring, we drove our boats to the Great Salt Lake—the only place for miles with enough water to row on. The lake’s salty water stank of sulfur, which made everything it touched stink, too. Thousands of brine flies swarmed our docks. They’d carpet my arms so thickly that when I looked down, I’d see more flies than flesh.

But away from shore, I could spot beauty all around. The water would stretch so far in every direction that I couldn’t see the land beyond. Unless the wind picked up, the lake lay flat, gleaming, and blue. Mountains pierced its surface and cloned themselves in the ripples below. They looked like spinning tops—stretching from peaks to flared bases, then winnowing back to sharp points.

I noticed with awe how the lake teemed with life. I’d look down, and what I thought were floating flakes of sediment would begin to swim. They were brine shrimp: crustaceans that carry the Great Salt Lake’s ecosystem on their centimeter-long backs. Waterfowl would fill the sky, diving to dip their beaks and spindly legs into my wake.

The year I left for college, one of my sisters joined the crew team. I hoped we could bond over rowing on the lake. But that November, a former teammate called me. She said our team wasn’t rowing on the Great Salt Lake that next year; that they might never row on it again. Utah was in a water shortage, and the lake had shriveled to its lowest levels on record.

The shoreline had receded so much that our docks became unusable. Most boats had been hauled out of the water as it crept down their bows. The boats that remained lay beached in a dry marina—a ghost town where, just months before, I’d rowed every afternoon.

Current Issue

The Great Salt Lake sits 20 miles northwest of my house in Salt Lake City. You see it whenever you look at the horizon: a streak of silver separating land and sky.

From its perch, the Great Salt Lake sustains all of northern Utah. Moisture evaporates from the lake and falls in the nearby mountains (mostly as snow, giving Utah fabulous skiing). Come spring, this water trickles through Utah’s valleys and returns to the lake. On its way, it hydrates the plants, animals, and people along the nearby Wasatch Front, home to Salt Lake City.

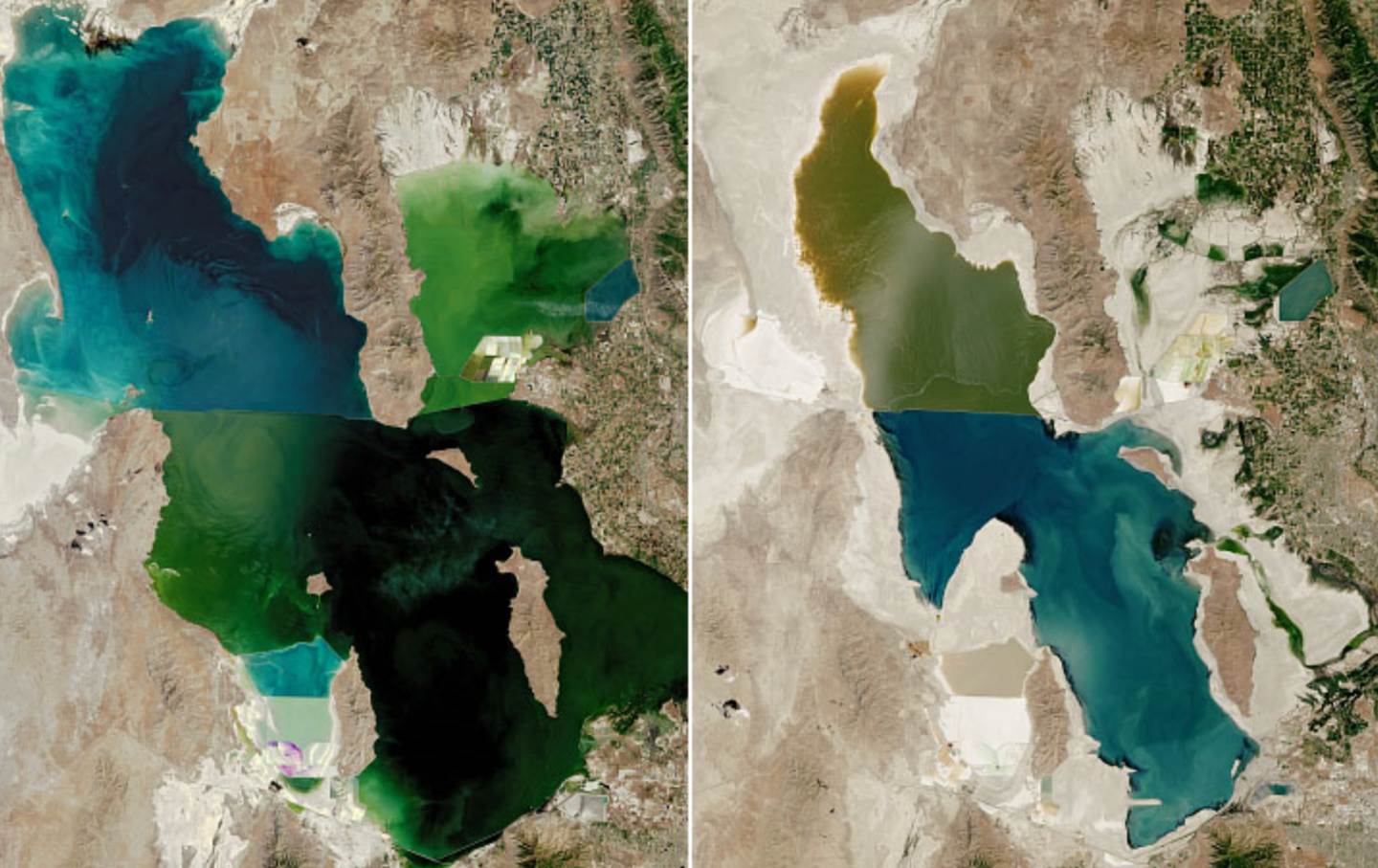

When I first visited the Great Salt Lake on a fifth-grade field trip, it covered 1,700 square miles. Though I didn’t know it yet, this was half of its size 30 years before, when my mom was a fifth-grader. In the 1980s, Great Salt Lake spread over 3,300 square miles—larger than Rhode Island and Delaware combined.

Now, my youngest sisters are in fifth grade. And again, the lake has halved, dropping to 888 square miles in 2022. Without meaningful change, the Great Salt Lake will vanish within my lifetime.

This would spell catastrophe for Utah. The New York Times says the Great Salt Lake’s disappearance would constitute an “environmental nuclear bomb.” Water supplies would dwindle, and ecosystems would perish: from the brine shrimp in the lake to the over 10 million migratory birds that refuel in its marshes each year. Utah’s population may vanish with them.

When Utah industrialized, mines began dumping waste into the lake, polluting it with heavy metals like arsenic. As a terminal lake, the Great Salt Lake has inlets but no outlets other than evaporation. All the metals that have ever been poured into the Great Salt Lake have accumulated in its lakebed over time, with no way out.

Now, retreating water levels are exposing stretches of cracked, arsenic-laden lakebed. Windstorms have begun to blow across the lakebed, picking up clouds of poisonous dust. They carry it into the Wasatch Front, which houses 2.8 million of Utah’s 3.4 million residents.

Even inhaling ordinary dust can be devastating to health. Arsenic-laced dust storms from the Great Salt Lake’s dried lakebed carry an extra hazard. When these storms arrive, the air will turn toxic. Millions of Utahns along the Wasatch Front—including my entire family—will breathe poison.

This dust won’t kill you overnight, but the EPA links it to “asthma, heart attacks, and premature death.” Similar disasters have happened to other lakes, and nearby cities have not fared well. After Owens Lake, a saline lake in California, dried up and toxic dust storms started, cities along its coast emptied. The arid lakebed filled the surrounding air with PM10—tiny particles that have serious health effects if inhaled. Owens Lake became the nation’s largest single PM10 source, spreading pollution across the West. The Great Salt Lake is 15 times larger than Owens Lake ever was. Its collapse would be far more catastrophic.

It terrifies me, thinking of what would happen to my community if the Great Salt Lake vanished. My little siblings all have severe asthma, and two live with just 60 percent of normal lung capacity.

When my brother visited the Great Salt Lake on his own fifth-grade field trip, his rowdy class kicked up dust on the lakeshore, which plunged him into a severe asthma attack. Fortunately, he had his inhaler ready. But what would happen to my siblings if these dust storms invade Salt Lake City? And the air outside his house? Could he survive in a place where he could barely breathe?

If the lake fully dries up, I know my family has the means to leave Utah, and we will.

This is what happened to the cities around Owens Lake. Those who could afford it fled. The less fortunate stayed and dealt with the consequences.

The next few years will determine the Great Salt Lake’s fate. Utah faces two options. We can respond with apathy and watch as the lake disappears, along with many of Utah’s residents. Or we can wake up to the danger we’re in. Enact substantive legislation, offer water conservation incentives, and appropriate money to save the lake.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Saving the Great Salt Lake won’t be easy. The University of Utah estimates that 33 percent more water must flow into the lake each year for it to reach healthy water levels by the 2050s. This means Utahns will have to make sacrifices. We must curb municipal water use—by getting rid of water-intensive lawns, for example.

Utah agriculture, the largest consumer of water from the lake, must also reduce its water intake. It likely won’t do this on its own, so Utah’s legislature must take action. Utah’s government must tighten water use regulations around thirsty crops like alfalfa, and invest state funds to lease water rights back from agricultural groups so more water can flow to the lake.

These actions will be politically charged and economically costly in the short term. But they will ensure that Utah, its people, and its industries last far into the future.

I worry that my siblings may never know the Utah I know. My littlest sisters are 10 years younger than me, and a lot can change in a decade. Will they ever ski through lake-effect snow, or find themselves enveloped in the brilliant sunsets you only see rowing on the Great Salt Lake?

I pray they will. But more than that, I count on myself and other Utahns to take action.

More from The Nation

An extraordinary eyewitness report reveals that food isn’t the only thing Palestinians are starved of. Fuel is almost as scarce.

Mark Hertsgaard

The International Court of Justice’s ruling that countries have a legal duty to curb climate change was the result of a yearslong campaign that began with university students.

Panthea Lee

Americans still don’t comprehend how imminent, dangerous, and far-reaching the threat is—and journalists are partly to blame.

Mark Hertsgaard

While the White House takes a sledgehammer to critical climate policy, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights announced a landmark decision on climate change and human rights.

StudentNation

/

Ilana Cohen

US Senator Sheldon Whitehouse called on Democrats to stop enabling the fossil fuel industry’s “malevolent propaganda operation.”

Mark Hertsgaard

It’s an extraordinary popular mandate that extends across partisan divides and national borders.

Mark Hertsgaard