Economy

/

September 18, 2025

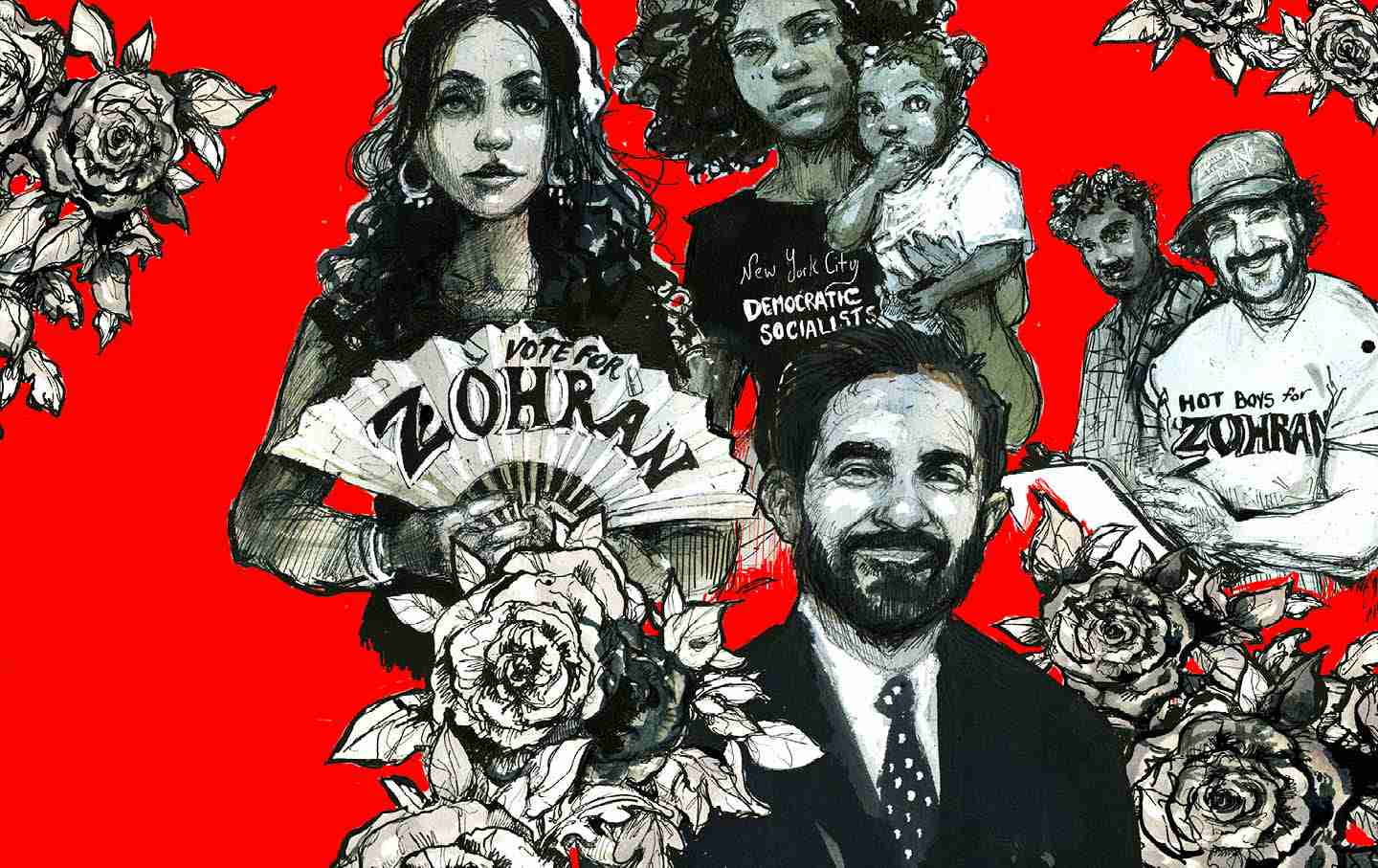

Trump’s brand of authoritarianism emerges out of New York City’s real estate industry. As mayor, Zohran Mamdani vows to curb that sector’s outsized power. A fight is coming.

Donald Trump, real estate mogul, poses in the foyer of his home in August 1987 in Greenwich, Connecticut.

(Joe McNally / Getty Images)

When the Trump administration deployed the National Guard to Washington, DC, and took control of the city’s police, the country advanced further into authoritarianism. After having already sent the National Guard to Los Angeles, Trump claimed the federal takeover of DC would bring law and order to the nation’s capital, which he characterized as “one of the most dangerous cities anywhere in the world.” In announcing the move, Trump emphasized his “natural instinct as a real estate person.” His background as a property developer, he said, made him uniquely well-suited to deal with urban crime and homelessness.

Trump’s acknowledgement of the link between his past business practices and his approach to governance is revealing: It grounds his particular brand of despotism in the politics of 1980s New York City. This link is especially important given the looming clash between the Trump administration and the presumptive next mayor of New York, democratic socialist Zohran Mamdani, whose political commitments threaten the neoliberal compact that has characterized the city’s political economy since the resolution of the fiscal crisis in the 1970s. Mamdani’s housing platform in particular aims to curb the outsize power of New York’s real estate sector, the milieu in which Trump rose to prominence in the late 1970s and ’80s.

New York’s fiscal crisis had its roots in a series of political-economic shifts that eroded the post–World War II liberal order. In the early 1970s, following years of white middle-class flight to the suburbs and capital flight to the Sunbelt and Global South, New York City found itself unable to raise enough tax revenue to keep funding the social programs that comprised its famed social-democratic polity. In late 1974, amid a global recession, the institutional investors that had been keeping New York City afloat stopped buying up municipal debt, pushing the city toward insolvency. The Ford administration refused to bail out the city, and after several tense months, the city came to an agreement with New York State to avert bankruptcy.

Current Issue

But the costs of this pact were steep, especially for working-class Black and brown New Yorkers, whose alleged profligacy was often blamed for the crisis. In exchange for the state bailout, New York City lost sovereignty over key areas of municipal governance and was forced to accept harsh austerity measures—thousands of municipal workers were laid off and many others had their wages frozen; social services were slashed, and public transportation fares were increased. Property values in the city dropped, particularly in working-class neighborhoods, where landlords often found it more profitable to abandon—and even burn down—their buildings rather than maintain them. The Bronx alone averaged as many as 40 fires per night in the mid-1970s; these fires led to the destruction of an estimated 80 percent of the South Bronx’s housing stock.

If every crisis is also an opportunity, New York’s near-bankruptcy was an opening for elites to discipline a restive working class and to reconfigure the city’s political economy along market-friendly lines. When the dust settled on the fiscal crisis, New York’s social-democratic polity had been whittled down, its institutions weakened by austerity, and real estate and finance interests were more powerful than before. To this end, the geographer Samuel Stein has characterized what emerged in New York City in the mid-1970s as the “real estate state,” a political economic paradigm in which “land is a commodity and so is everything atop it; property rights are sacred and should never be impinged; a healthy real estate market is the measure of a healthy city; growth is… god.”

This is the landscape in which Trumpism was formed. Piggybacking on wealth generated by his father’s substantial real estate holdings in the outer boroughs, Trump began acquiring land in Manhattan in the late-1970s, just after the resolution of the fiscal crisis. His first major development was Trump Tower, the construction of which began in 1979 and was completed in 1983. He continued to purchase Manhattan real estate, including the Lincoln West development in 1984, and expanded the geographical footprint of his portfolio with a series of now-infamous casino deals in Atlantic City. According to a New York Times investigation from 2018, Trump’s fortune was based in significant part on a combination of tax dodges, government largesse, and lax regulatory oversight, all of which grew the wealth that he had been collecting since childhood—wealth that was derived from his father’s activity as a real estate developer and landlord.

Trump’s ascent in New York’s post–fiscal crisis real estate state was inflected by racism, which has long been a structuring force in the real estate sector. In a 1973 federal case that resulted in a consent decree, the Justice Department sued Trump and his father under the Fair Housing Act for refusing to rent apartments to Black and Puerto Rican tenants. Several years later, the government accused the Trumps of continuing to steer minority tenants to buildings that were already populated with people of color.

Beyond the confines of his real estate practices, Trump apparently soaked up the racist law-and-order commonsense of the post-crisis years—in 1989, in a move with echoes in the present, he took out a full-page advertisement in The New York Times, calling for the death penalty for the Central Park Five, a group of Black and Latino men who had been arrested and were later wrongfully convicted of the rape of a jogger in Central Park. Even after the men were exonerated, Trump did not apologize.

There is a through line from Trump’s career as a New York City real estate developer to his approach to wielding state power. As with the elites who reshaped New York in the wake of its near bankruptcy in the 1970s, in the run-up to the 2016 election, then-candidate Trump exploited a crisis of legitimation (of the neoliberal project following the financial collapse of 2008 and decades of abandonment of working people by both major political parties) to seize power. Like a real estate developer bent on eliminating costly regulation, Trump has moved aggressively to dismantle the administrative state—from drastic cuts to a range of federal agencies to slashing public benefits for poor and working people. The administration’s signature legislative achievement has been to transfer wealth upward by giving massive tax breaks to the already rich—tax breaks not unlike the ones the Trump family exploited to build their real estate wealth. Trump has governed largely according to the blueprint that was rolled out during the city’s fiscal crisis and its aftermath, leveraging racism to discipline the working class and enhance the power of economic elites.

Most recently, as Trump’s federal takeover of Washington, DC, makes clear, his approach to addressing perceived urban problems is to reflexively racialize them, cast them in an idiom of law and order, and then over-police them. This approach comes into focus when viewed as the necessary underside to the real estate state’s worship of property values. As the philosopher Antonio Negri wrote about the advent of neoliberalism, “The ‘new Right’ ideology of laissez-faire implies as its corollary the extension of new techniques of coercive and state intervention in society at large.”

Trump now appears to be on a collision course with New York City. He is threatening federal funding cuts and to deploy the National Guard, saying, “We’re going to straighten out New York.” With democratic socialist Zohran Mamdani poised to be the city’s next mayor, the real estate state that emerged out of the fiscal crisis of the 1970s is on shaky ground. Mamdani has campaigned on a vision of a city that working-class New Yorkers can afford, with specific policies—a rent freeze, fast and free buses, a public option for groceries, expanded universal childcare—to back it up. Perhaps just as importantly, his Democratic primary victory over rival Andrew Cuomo, energized by a network of more than 40,000 volunteers, was, in the words of Liza Featherstone, “a straightforward triumph of people over money.”

In this sense, a Mamdani mayoralty poses a genuine threat to the elites who constructed and benefited from the neoliberal order established in New York in the 1970s. It threatens to undermine the austere, market-friendly ideological framework that amplified the power of real estate at the expense of tenants and workers—a framework with property values and violent policing at its core. In other words, the clash between Trump and Mamdani, when it comes, will be a fight between competing visions of how society ought to be organized, and despite its national implications, the fight will be a decidedly New York City affair.

Don’t let JD Vance silence our independent journalism

On September 15, Vice President JD Vance attacked The Nation while hosting The Charlie Kirk Show.

In a clip seen millions of times, Vance singled out The Nation in a dog whistle to his far-right followers. Predictably, a torrent of abuse followed.

Throughout our 160 years of publishing fierce, independent journalism, we’ve operated with the belief that dissent is the highest form of patriotism. We’ve been criticized by both Democratic and Republican officeholders—and we’re pleased that the White House is reading The Nation. As long as Vance is free to criticize us and we are free to criticize him, the American experiment will continue as it should.

To correct the record on Vance’s false claims about the source of our funding: The Nation is proudly reader-supported by progressives like you who support independent journalism and won’t be intimidated by those in power.

Vance and Trump administration officials also laid out their plans for widespread repression against progressive groups. Instead of calling for national healing, the administration is using Kirk’s death as pretext for a concerted attack on Trump’s enemies on the left.

Now we know The Nation is front and center on their minds.

Your support today will make our critical work possible in the months and years ahead. If you believe in the First Amendment right to maintain a free and independent press, please donate today.

With gratitude,

Bhaskar Sunkara

President, The Nation

More from The Nation

When the senator came to New York in early September, he had a few spare minutes to talk municipal politics and governance with one of his biggest fans, Zohran Mamdani.

Q&A

/

Zohran Mamdani and Sen. Bernie Sanders

All over the country, young Democratic candidates are running seemingly Mamdani-style campaigns. But check the fine print.

Aaron Narraph Fernando

The unsung hero of Mamdani’s campaign is its field operation. It may make him mayor of New York City.

Feature

/

Hadas Thier

New legislation could accelerate a growing movement of tenants who refuse to be at the mercy of developers and want to take ownership of their communities’ resources.

Aviva Stahl

We have an unprecedented chance to elect a mayor who can prioritize the needs of working people.

Bill de Blasio