October 21, 2025

What drives Trump’s politics is nostalgia for the age of coal, when dirty fuel and no environmental regulations created his version of a great America.

Arguably, no technology freed the world from the drudgery and cold of premodern times more than coal. It fueled the Industrial Revolution and rising standards of living that transformed what a human life meant after 1800. The cost of this freedom soon meant slaughtered workers, rising carbon dioxide levels, and the threat of planetary ecological catastrophe.

Today, arguably no technology dooms the world’s future more than coal, with its environmental destruction, pumping of carbon dioxide into the air, and dangerous working conditions that still kill from work, pollution, and climate change. The environmental journalist Robert Wyss provides readers an often-dramatic episodic overview of coal in American history, the great paradox between power and destruction that we could escape today, but we choose not to because of vested corporate interests and Donald Trump’s nostalgia for an America where coal burned plentifully and white men like himself ruled the world.

A cheap, plentiful energy source that could power factories anywhere provided enormous financial benefits, and coal revolutionized the global economy. Early factories relied on waterpower, clean in terms of what were then unknown carbon emissions, but limited development to waterways. Coal transformed the geography of industrialization, allowing enormous industrial operations wherever a capitalist wanted to build. It fueled steel and railroads. It heated homes—dirtily, but in a 19th-century working-class home, avoiding the cold took precedence for most family over smoke. The idea of fossil fuels raising standards of living powers the ideology of many of Trump’s energy advisers, who not coincidentally often have vested financial interests in the industry. They ignore or lie about the massive human and environmental cost.

As Wyss reminds readers repeatedly, coal’s horrors showed up quickly. An entrepreneur could easily post a hole in the ground and find workers to dig out the coal. Beginning shortly after 1800, mines began shipping coal to eastern cities. In an era without regulations, where the courts consistently ruled that employers owed workers nothing if they died or were injured on the job because no one forced them to take that particular job, it did not take long for the workers to start dying from cave-ins, gas explosions, and employer indifference to their lives. Wyss juxtaposes the Centennial Exhibition held in Philadelphia in 1876 that celebrated the industrial might of an America running on coal with workers going days without seeing daylight, racial tensions in the mines as companies used Black strikebreakers, and death from accidents.

Unsurprisingly, workers began to organize. The nation’s most infamous early labor organization—the Molly Maguires—were an early response to the terrible conditions in the Pennsylvania mines that became associated with terrorism. Men such as Andrew Carnegie and Henry Clay Frick would stop at nothing to keep their coal-fueled steel mills nonunion, and this allows Wyss to tell the story of the Pinkerton invasion at Homestead, Pennsylvania, during the famous 1892 strike at Carnegie Steel. The United Mine Workers would form in 1890 and provide a more respectable sort of unionism. But over time, the UMWA became part of the machine keeping the nation enslaved to coal. Legendary UMWA president John L. Lewis fought like hell for his men, as Wyss explores, with attention to the details of workplace health and safety driving strikes, but he was also a tyrant and a man who believed himself and his union more centrally powerful to the American future than it turned out to be.

Coal also blackened the nation’s collective lungs, both inside the mines and outside where coal smoke blotted out the sun. Wyss tells the story the early 20th century attempts to clean the nation’s filthy city air of coal smoke, a process often led by women who found political space to take on urban reforms based on gendered stereotypes around motherhood, framing this by protecting their children from polluting industry. They struggled to succeed in a world dominated by an ideology of endless industrial growth. Finally, in the 1970s, environmental movements began taming coal, a story Wyss tells by focusing on the Navajo Generating Station in Arizona. As ever, coal divided Americans, in this case the Navajo on whose land the power plant resided and upon which tribal leaders relied for scarce financial resources.

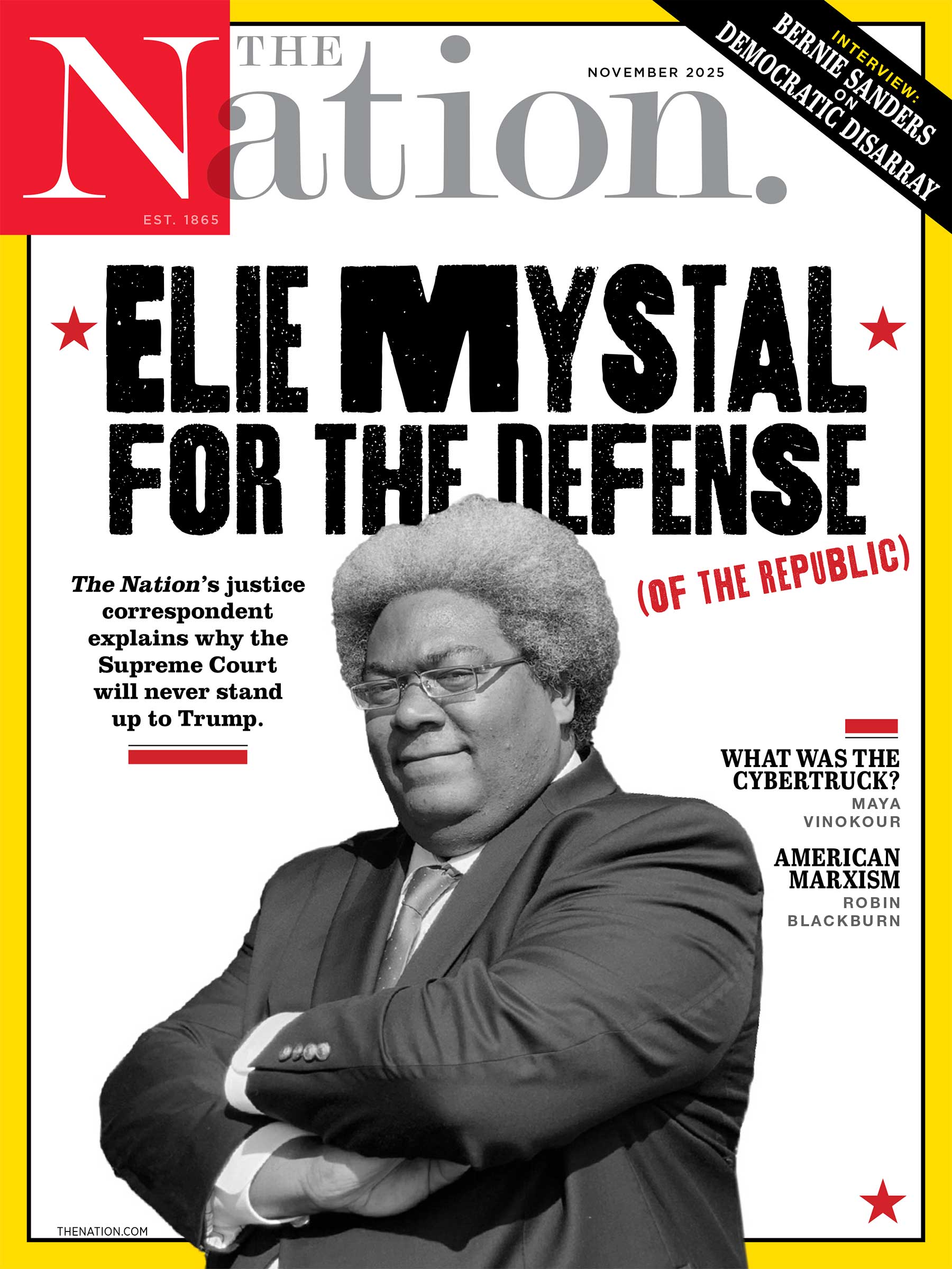

Current Issue

Wyss powerfully describes how coal still destroys life and landscapes today. He tells powerful stories of miners dying from black lung, of mountaintop removal mining reshaping the geology of Kentucky and West Virginia, the waste flowing into the river bottoms and the devastating floods that result. Wyss sees coal slowly disappearing from the American landscape. The Navajo Generating Station was blown up in 2020, and the rise of reliable clean energy should usher in the end of coal. But will it be too late for humans to reverse course on climate change?

Wyss actually skips over much of coal’s history, including the iconic labor battles over control of the mines. He could have easily doubled the book’s length telling dramatic and often violent stories. Some would have strengthened the book. Take the history of coal in Colorado. Wyss omits the Ludlow Massacre, where workers in a Rockefeller-owned mine struck and the Colorado National Guard and company guards opened fire on the camp in 1914, killing over a dozen women and children camping in a tent town. What followed was weeks of warfare in which possibly 200 people died and which the historian Thomas Andrews has called the deadliest strike in American history in his book Killing for Coal. The violence led the US Commission on Industrial Relations to haul John D. Rockefeller Jr. on stand for embarrassing public testimony about his indifference to the conditions of work in his mines. And then when the Industrial Workers of World struck at the Columbine Mine in that state in 1927, its young owner, Josephine Roche, was so horrified about conditions in the mine she inherited from her father that she invited the United Mine Workers in to unionize her workers, later becoming a top labor official in the New Deal and finally running the UMWA retirement fund for over 20 years. So yeah, coal’s history is pretty dramatic.

But I don’t blame Wyss for leaving out these stories. Coal plays such a dominant role in American history, so overwhelming in its negative impact on workers and the environment that any author must make hard choices to avoid either a thousand-page doorstop or a boring compendium of facts. Instead, he takes the anecdotes he chooses and writes them with great power and energy.

Wyss wrote this book before Donald Trump returned to the presidency, but Trump’s energy policy revolves around nostalgia for burning fossil fuels. The administration has shut down wind and solar projects around the nation, including the Revolution Wind development off the shore of Rhode Island, an 80 precent completed project that had employed over 1,000 union workers. Purportedly, this is the type of job Trump wants to see return to the United States. This has great appeal in America’s coal regions. Despite the horrors that Wyss so accurately describes, coal provided the best jobs that have ever existed these parts of America.

Democrats have failed as badly as Republicans in articulating and following through on alternative economic models for coal country, and until they step up their game, the Trumpist nostalgia for coal will likely continue to drive politics for a big chunk of America, despite all the horrors Wyss so powerfully describes. So, when he wonders if America will get off coal before it’s too late, the answer might well be no and for the most exasperating possible reasons. But whatever, it’s only the future of humanity and most of the planet’s species on the line here. What is that compared to some good ol’fashioned lib-hating burning of fossil fuels?