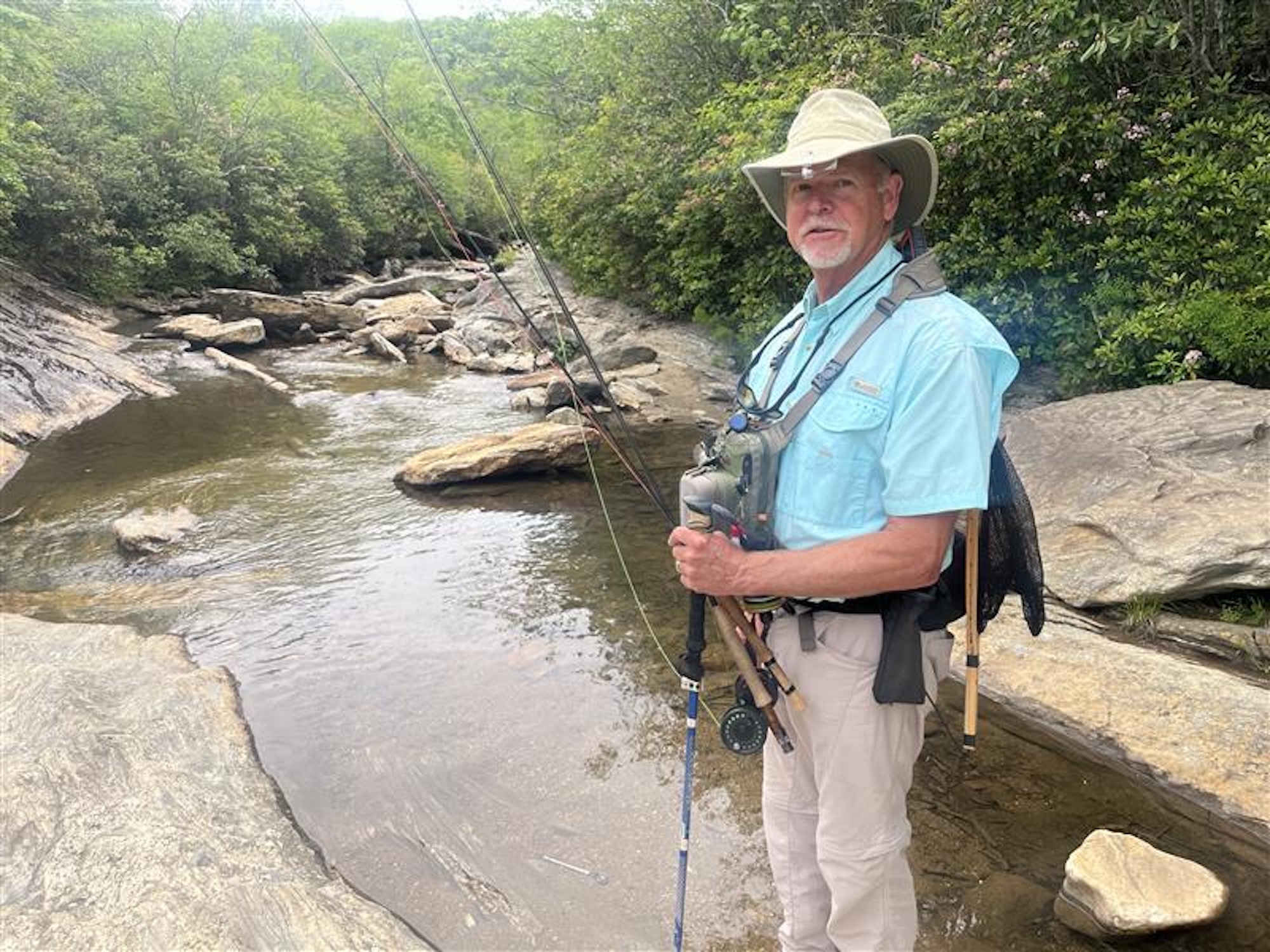

On a startlingly beautiful day high in the Blue Ridge Mountains, Thomas Champeau waded into Yellowstone Prong hoping to catch the elusive Southern Appalachian brook trout. A pull-off along Blue Ridge Parkway had led him to a short path lined with mountain laurel. He and a smattering of afternoon anglers followed it to a rocky creekbed running cold and clear toward the Pigeon River. Champeau, already in waders, left a cooler on the bank in case of a lucky catch and stepped in. Rod in hand, he treaded lightly from one smooth rock to another, carefully staying out of sight of his quarry. Brook trout are, like Champeau, alert, cautious, and observant, hanging tight in the shaded pools where they make their home.

“Your approach has to be low, quiet, and so it’s a little bit like hunting ‘cause you’re kind of stalking as opposed to just fishing blindly,” Champeau, a former biologist who runs communications for a local chapter of Trout Unlimited, said. After an unsuccessful cast he reeled the line back in and moved upstream.

All around, the landscape was blooming and greening with summer. It still bears the scars left by Hurricane Helene, which tore through the region in September 2024. Trillions of gallons of rain turned placid streams into raging torrents that overran homes and forests. The storm upended streams and radically remade trout habitat. Researchers and anglers looking for the fish have navigated eroded streambanks, downed logs, and debris. “Rocks bigger than a refrigerator have been pushed around,” Champeau said while casting into a calm pool.

Katie Myers / Blue Ridge Public Radio / Grist

The upheaval was particularly hard on the Southern Appalachian brook trout, a fragile, cold-water native that has endured more than a century of logging, development, and competition from introduced species. Once abundant across the region for which it is named, the fish has lost roughly 80 percent of its range since 1900. Because the animal is so sensitive to pollution and temperature changes, biologists consider it a bellwether for the region’s forests and streams. They find its rapid decline alarming — not only because they care about trout, but because trout can only survive in healthy waterways. Helene’s damage raises the larger question of whether one of Appalachia’s most iconic fish — and the ecologies, economies, and traditions tied to it — can adapt to a rapidly changing climate.

“When it comes to climate change, sometimes it’s going to be a death by a thousand cuts,” Champeau said. “And it may not be one big storm that says, ‘Oh, well, you know, this big storm caused this to happen.’ But, you know, it’s the losses that happen over time.”

Katie Myers / Blue Ridge Public Radio / Grist

For all their individual frailty, as a species, the Southern Appalachian brook trout has endured immense ecological change. The iridescent fish, olive-colored, speckled, and red-bellied, has been adapting to the region’s cold-water rivers for thousands of generations, having evolved in isolation in high mountain habitats from Georgia to Southern Virginia since the Ice Age. Though they are usually no more than 6 or 8 inches long, these small predators are a keystone species, and their loss would disrupt those ecosystems.

The Industrial Age has proven a far tougher challenge for them. Extensive deforestation in the early 20th century took away shade that keeps streams cool and led to ongoing habitat encroachment and development. The introduction of larger, nonnative trout species like browns and rainbows — both popular with anglers — left them competing for food and territory. Now, climate-induced vacillations between extreme rain and long, dry months when streams run lower and warmer further threaten the brookie, as the fish is affectionately known among locals.

Katie Myers / Blue Ridge Public Radio / Grist

Climate change poses a particularly serious threat to Salvelinus fontinalis. The fish favor cold, shaded forest streams and do best in water no warmer than 68 degrees Fahrenheit. They tend to spend their entire lives within a few hundred yards of where they hatched, making them highly vulnerable to even small changes in their habitat.

Researchers have observed startling declines in places like Shenandoah National Park in southwestern Virginia, where one study found they plummeted by 50 percent in nearly all of the park’s 90 streams in just the last three decades. Those who had seen hundreds of them in some waterways in the 1990s have been shocked to see single digit populations today. In at least three cases, brook trout had vanished entirely. Scientists worry that the fish, which is not federally listed as endangered or even threatened, could be pinched out at the southern end of its range as waterways grow warmer. An average stream temperature increase of just 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit could eliminate another 20 percent of Southern Appalachian brook trout habitat. “They need to adapt quickly,” Champeau said.

Compounding the threat are storms like Helene, which dumped as much as 30 inches of rain on parts of the Blue Ridge. The floods overwhelmed hundreds of streams and sent about 7 million cubic yards of debris flowing into waterway ecosystems. Biologists fear the inundation washed brook trout away from their home pools and interrupted their spawning season.

Champeau is working to educate local anglers on the risks. Many of them aren’t thinking about climate change on the daily, and aren’t predisposed to worry about it. But when storms threaten trout, that can change.

Katie Myers / Blue Ridge Public Radio / Grist

As brook trout vanish, the loss runs deeper than the eddies and pools where they once thrived. Brookies are more than a fish. They’re a cultural touchstone “as important as bluegrass,” Champeau said. Climate change and storms like Helene threaten not only a species but an identity and economy. Trout fishing generates $1.4 billion for Western North Carolina alone. People come from far and wide hoping to reel in rainbows and browns, but longtime residents cherish brookies, which also are called specks for the red dots that cover their backs and sides. Hooking one of the wary, cautious creatures demands patience and skill. Locals balance their love for them with the understanding that it’s the larger, flashier species that pay the bills.

“The native brook trout was the first trout I ever caught,” said Mitch Carter, a fishing guide from Asheville who’s currently out of work after Helene. But “an 8-inch brook trout doesn’t sell licenses, right? Native brook trout protection is honestly an emotional thing, I feel like you kind of have to be from here, and even if you’re not from here, you have to have a deep understanding of what it means to have this fish here.”

Kevin Howell understands that. He owns Davidson River Outfitters, a beloved shop at the mouth of the Pisgah River in Brevard, North Carolina. Helene hasn’t made that work easy, though. The flooding scoured away access to many spots or cluttered them with fallen trees, and he turned the shop into a recovery supply depot for a couple of weeks. “We did lose our two busiest months of the fall,” Howell said. It’s a large shop and could sustain the loss, but others couldn’t. “A lot of the smaller guides were significantly impacted and it hurt their income for the year. Some of them even left guiding, or they moved.”

Howell grew up fishing the local waters and thought he knew them well. But Helene rendered them unrecognizable, and the cleanup further damaged streams and the trees that keep them cool during hot summers. “[It added] to the sedimentation and the warmer temperatures, which again results in less fishable water and less fish and less habitat,” Howell said.

Even a short-term increase in water temperature can threaten brookies, which experience heat stress at 68 degrees Fahrenheit and stop growing once it hits 70. That’s why fishing is strictly a catch-and-release endeavor during the summer. But warmer water also holds less oxygen, meaning trout that have been reeled in and tossed back are less likely to survive the shock. “We had to make the decision today to stop fishing at noon because in the afternoons it’s getting to 68 degrees already in June,” Howell said. “Which is very early.”

Most of Howell’s customers are after brown and rainbow trout. Though he loves brookies, he worries scientists are fighting a losing battle trying to save them. He doesn’t feel that efforts to reintroduce them have been successful. Competition from the larger, more aggressive varieties is too great. Given their dwindling numbers and mounting threats, he doesn’t tell anglers where to find the native fish, in hopes people will leave them well enough alone.

The interplay between economics and emotion has driven decades of brook trout conservation by the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Indians. Mike LaVoie, the tribe’s director of natural resources, said healing their habitat is part of healing the long history of extraction and colonization that has left the Cherokee people with a fraction of their original territory.

“Cherokee have always viewed the river as a long person, so it was an embodied identity and given human attributes,” LaVoie said. “There’s just centuries of reverence and respect that was given to the long person based on Cherokee science, really. It’s all about understanding how to live within that landscape and waterscape and how to ensure that that remains healthy.”

Brook trout suffered in the initial years of logging when the timber barons gained steam in the 1890s, but they thrive in about 10 miles of high-elevation streams on tribal land, which is fiercely protected. “Most headwater populations of these fish are in our tribal reserve area, which has been set aside by the tribe for tribal member use,” LaVoie said.

This protection co-exists with a healthy culture of fishing and hunting, one the tribe relies on. Annual tournaments, gear shops, guiding, and hatchery work all thrive on the Qualla Boundary between North Carolina and Tennessee. Fishing brings the tribe $93 million and about 45,000 visitors annually, LaVoie said, much of that revenue from permit sales. They don’t stock fish in the headwaters in order to avoid conservation conflicts.

Katie Myers / Blue Ridge Public Radio / Grist

The tribe has initiated or collaborated on a number of studies and resiliency plans to assess how climate impacts could change the region and the fish so central to the local economy. Storms, fires, and increasing heat are changing the composition of the forests on the Qualla Boundary; LaVoie hopes a return to traditional controlled burns, an ancient Indigenous science, can restore the shady forests that keep the brookies’ waterways cool enough to sustain them.

Even as the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Indians looks to the future, biologists are assessing just what Helene has done to the brook trout population. Crews with the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission spent the summer counting fish and talking to anglers. “It doesn’t take long to find somebody that tells you a story about a grandparent or great grandparent fishing for specks,” Jacob Rash said as he led a team about a mile into the Pisgah National Forest.

Katie Myers / Blue Ridge Public Radio / Grist

The biologists stepped into their waders to ford the stream, which they zapped with low-voltage current. Fish floated to the surface, stunned but unharmed, and the crew carefully put them in buckets. Each was counted, weighed, and measured, then released. Most were browns and rainbows. After an hour of zig-zagging up the stream, the team crew caught an iridescent, red-finned brookie, which swam placidly in a bucket before its turn on the scale. They’ll keep doing this work for many years to understand Helene’s impact on spawning season, tracking generations of brook trout visiting the streams they inhabit, and restoring the habitat they rely upon. They missed some of that work last fall after Helene, and have been playing catch-up.

At the end of the day, the team released that lone brookie. It woke from its stupor and quickly darted away. It was the only one they saw, but still a positive sign, according to Rash. “I never stop being amazed at what these fish can do,” he said. “It’s just cool to see them persist and knowing they’ve been here for so long and they still find a way to make it.”

Katie Myers / Blue Ridge Public Radio / Grist

Back on the Yellowstone Prong, Thomas Champeau didn’t have the same luck. “But you never know!” he said, packing up. ”That’s why they call it ‘fishing’ and not ‘catching,’ right?”

For him, though, it’s not about catching or not catching. The time he spends in the streams is a sort of communion. Getting to share a home with this ancient species on mountains worn down from Himalayan heights over millions of years is reward enough. He only hopes he can help shepherd brookies through this tumultuous moment toward whatever might come next.