Activism

/

October 21, 2025

After the government betrayed them by refusing to enforce a crucial workplace health rule, a group of coal miners traveled to DC to put Trump on notice.

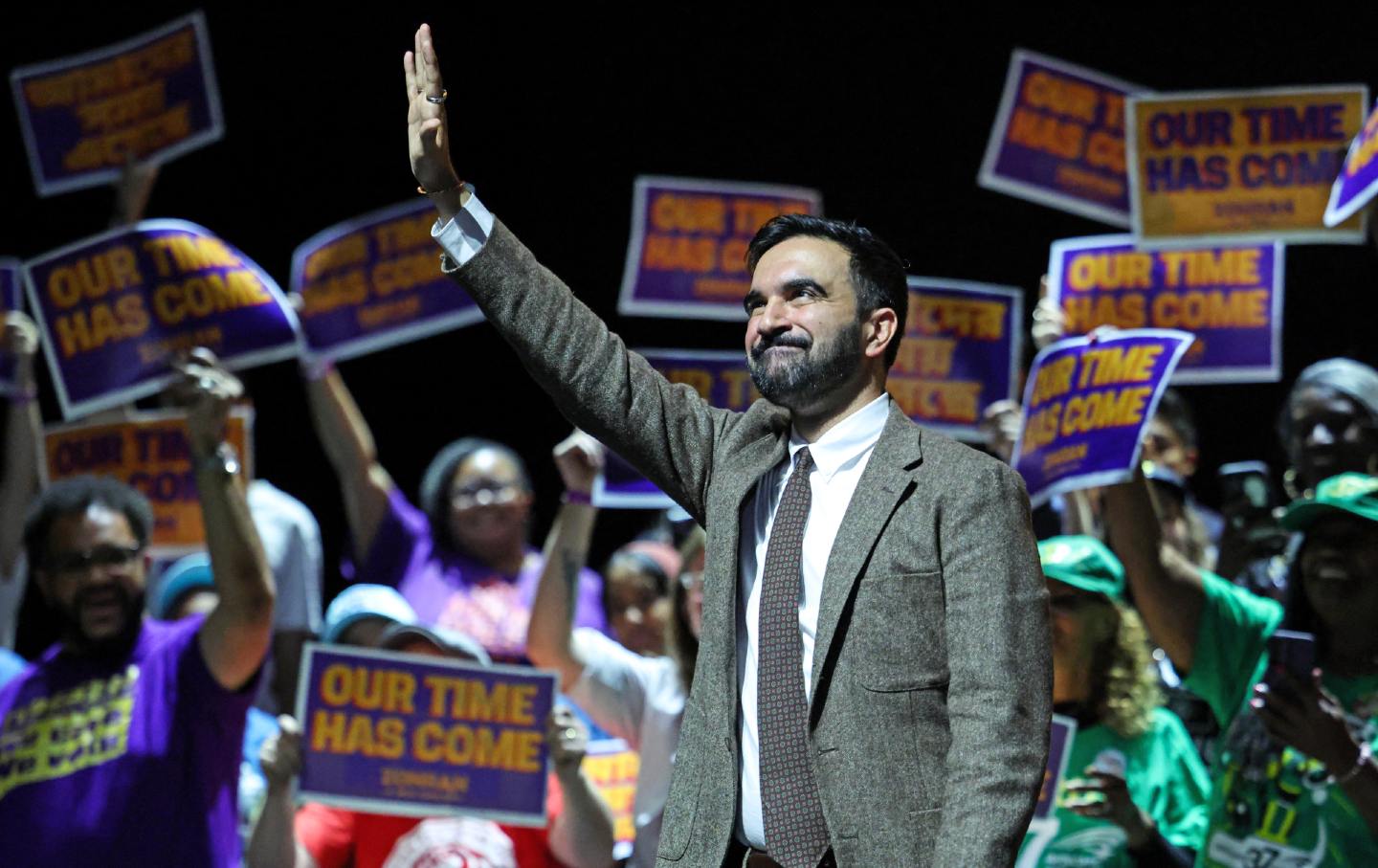

Protesters at the coal miners’ rally in Washington on October 14, 2025.

(Chelsea Barnes)

Last Tuesday, a small group of retired coal miners gathered in front of the headquarters of the Department of Labor with a rather ambitious goal: to get Donald Trump’s attention.

Due to the ongoing government shutdown, the streets of downtown Washington, DC, were far from bustling, but a few passersby still stopped to peer at the 80 or so camo-clad demonstrators and read the signs they bore: “Silica Kills,” Stand With Us! Enforce the Silica Rule!,” “Coal Miners Lives Matter.” The protest was an act of both proud determination and brutal desperation. A hard-won federal rule limiting miners’ exposure to respirable crystalline silica was meant to go into effect on April 14, but the Trump administration has refused to enforce it. The Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA), which is nestled within Trump’s Labor Department and is now led by a former coal industry executive, voluntarily allowed this to happen.

As I reported for In These Times, the rule would have cut the allowable exposure level of the deadly dust—20 times more toxic than coal dust and a major cause of black lung disease among coal miners—in half. The Department of Labor had estimated in 2024 that, with proper implementation and enforcement, the rule would save thousands of lives. Instead, coal miners across Appalachia continue to suffer from its absence. United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) International President Cecil E. Roberts characterized the delay as “a death sentence for more miners.”

Former Acting Secretary of Labor Julie Su agrees. “We strengthened respiratory protection standards for miners against all airborne hazards — not just silica dust,” she wrote recently. “Trump’s DOL is not enforcing this rule, and because of that, workers will die. This isn’t just cruel to miners. If Trump’s DOL reverses protections on one of the most dangerous jobs, what protections are they willing to enforce?”

There is no good reason for the delay, even taking into account various coal and construction industry lobbyists’ insistence that the rule is too onerous to follow. This is not a new problem, as they are well aware, and this silica standard is not particularly radical. Miners and public health experts have argued that the new 50-microgram threshold it sets is still far too high, and have expressed concerns that the rule’s current form will allow mine operators far too much leeway in terms of inspections and engineering controls. It’s also about 50 years too late.

Back in 1974, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health began sounding the alarm on silica and the dire threat it posed to the nation’s coal miners. It still took until now for even a watered-down regulation to make it (almost) out of the gate—that is, until Trump’s Department of Labor stopped it in its tracks.

Current Issue

This issue is not unique to coal miners. The danger that silica poses to the human body has been felt far beyond Appalachia and across numerous industries, from construction and metal/non-metal mining to countertop installation and long-haul trucking. Silica exposure can lead to an array of serious respiratory ailments, including lung cancer, emphysema, silicosis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, as well as the most severe form of black lung: progressive massive fibrosis. Coal miners do have several unfair disadvantages here, though. The current allowable level of exposure for every other type of worker in the country is set to 50 micrograms per cubic meter during a 10-hour shift; for coal miners, that number is doubled. In Central Appalachia, thinned-out coal seams and technological advances in heavy machinery have forced miners to dig through more and more rock in pursuit of coal—and that rock is laden with silica particles, which are released into the air with every hammer blow. Taken together, that means that many coal miners (particularly those who work underground) are exposed to much higher levels of silica than anyone else in America. As a result, more of them are getting sicker, faster. Black lung is no longer an “old man’s disease”—now, it’s coming for the young too.

“Unfortunately we’ve seen miners who have complicated black lung, or progressive massive fibrosis, with less than 10 years of coal mining experience,” Dr. Leonard Go ,pulmonologist and assistant director of the Mining and Education Research Center at the University of Illinois Chicago School of Public Health, told The Nation after the rally. “That could be people in their 20s, people who are young enough to be thinking about lung transplants— exchanging one disease for another. And to get a lung transplant, you have to have what’s referred to as end-stage lung disease; in a way, it’s kind of like having died. You would not live to 70, 80 years old with that lung disease if you’re getting transplanted in your 40s.”

That harsh reality is exactly what miners and occupational health experts have been trying to avoid for decades. While this new silica rule is only a step in the right direction, the fact that it’s been left to languish has imbued those who fought for it with a renewed sense of purpose. They’ve worked too hard for too long to see it fall apart now, and this latest betrayal is nearly too much to bear, especially coming as it does from an administration that has sold itself as “pro-coal” and committed to “the American worker.” On the other side of the DOL building, an enormous banner of Trump’s face stared blankly into space as the miners spoke haltingly about their agonizing plight. Some of the older women held color photos of their late husbands, who they had had to watch die from the dreaded disease.

There were many widows in attendance, but there was at least one retired miner there representing the industry’s strong but small female minority. 77-year-old Brenda Ellis spent 24 years working underground in the mines in her native Wyoming County, West Virginia. Nine years ago, she started to realize that something was wrong. “I was out of breath, I had no energy, gained all this weight and it just keeps on piling on,” she told me, wrinkling her nose. It took her six years to get diagnosed properly and access her black lung benefits. She’ll be starting oxygen soon, and will have to wheel around a tank of her own. That day, she was in DC representing her union, UMWA Local 1713 in Pineville, West Virginia, where she is the recording secretary and a fervent voice in the fight against black lung. She steadied herself on my arm, and looked up at me with a mischievous glint in her blue eyes. “I guess I’ll take it easy the day after I die!”

Ellis and most of the other miners had traveled long distances from their homes in various pockets of Appalachia in order to be there; they came by bus and by car, joined by union officials, advocates from the nonprofit Appalachian Voices and BlueGreen Alliance, members of the Steelworkers, and family members. A number of them were elderly and sported the telltale signs of severe lung disease: nasal cannulas and oxygen tanks. Some spoke in a gasping wheeze, straining for each breath. Others relied on mobility aids like canes and wheelchairs to find their positions, their lungs unable to power them for more than a few steps at a time. Hidden beneath their skull-adorned “Black Lung Kills” T-shirts were layers of damaged lung tissue that had been pocked and scarred by toxic dust. Black lung disease—known officially as coal workers’ pneumoconiosis (CWP), and by the old timers as miners’ asthma—is a devil they knew very, very well, and they’d made the difficult trek up to Washington to try and stop it from claiming a whole new generation of miners.

“We’re tired of seeing 28-year-olds with complicated black lung,” Vonda Robinson, Vice President of the National Black Lung Association, told the crowd. Her husband, John, is a retired miner who’s been struggling with black lung for years and is in need of a lung transplant. “We saw a 35-year-old die last week. These people are not going to see their children grow up…. We’re asking President Trump, Vice President Vance, and Congressman Griffith to get this done. We need your Republican support to get this passed because, without this, it’s an early death sentence for our miners. And they deserve to be able to breathe, they deserve to be able to go home to their families. We’re here to make America healthy again, too. We need that for our miners. We need your help with this rule.”

By calling on Trump by name, Robinson and the other speakers emphasized the outsize role that coal has played in the president’s carefully crafted public mythos (as well as that of his underling Vice President JD Vance, a self-styled son of Appalachia who has not said a single word about the black lung crisis). In 2016, Trump was balancing a miner’s helmet atop his ramshackle coif and grandly proclaiming, “Trump digs coal!” at a campaign rally in West Virginia; nearly a decade later, the coal industry is in a death spiral and the nation’s 33,000 remaining coal miners are staring down the barrel of a brutal early death unless his administration takes action on one simple obligation. Trump failed to “bring back coal” the way he promised during his first term, and while many voters in Appalachia’s coal country still gave him a second chance, it’s become apparent that all of his promises were worth about as much as a truckload of coal dust.

“I’ve been coming up here for 20-some years to get this silica rule and get it enforced,” Gary Hairston, president of the National Black Lung Association, said during the rally, his breath catching in his throat after every few words. “Congress y’all ain’t doing nothing for us. We need you all to stand up for us coal miners. You have us stand beside you when you run for election, and now we need your help. We need your help right now. We need the silica rule. We need it enforced.”

Brian Sanson, the UMWA’s international secretary-treasurer, was even more frank. Under the new regime, MSHA has not only stonewalled the union on communications, it has also canceled long-standing grants for miners’ health and safety education (reread the name of the agency, then read that again). In Sanson’s estimation, Trump’s claims of caring about coal miners are pure bunk. “This administration loves coal companies—I think there’s a difference.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

“Look, this is from the top down,” he explained to The Nation. “This is a systematic cancer in our government that needs to be purged. It’s a lack of enforcement, it’s a lack of safety rules and regulations. Workers’ health and safety has definitely gone by the wayside under this administration.”

For now, Sanson and everyone else there that morning are hoping that they’ll be able to catch the president’s attention and remind him of what he owes them.

“We petition the president of the United States, the director of MSHA, and the secretary of labor to stand and fight for the people of Appalachia,” boomed UMWA’s president, sixth-generation coal miner Cecil Roberts, in his well-practiced preacher’s roar. “We want representation, we want healthcare, we want to end this plague that’s going on in the coalfields of the United States. Let’s lift those up today who are suffering from pneumoconiosis, those on oxygen, those in wheelchairs. We ask our government to see us, see us and do something for us. Let’s stop the killing in Appalachia. All we want is justice. We want fairness. And we want it right now.”

This coal miners’ gathering, like so many others, ended with a sermon and a prayer—to the president, to Congress, and to anybody else out there who was listening. “We declare that you have a moral imperative to make this happen,” the Rev. Brad Davis, a pastor who serves coalfield communities in McDowell County, West Virginia, thundered as the rally came to an end. “Then and only then will we echo the late, grea tHazel Dickens, “Black lung, black lung, you’re just biding your time. Soon all of your suffering will be less.”

More from The Nation

The decisive factor isn’t his ads or charisma. It is the public financing of election campaigns, and it should be replicated across the United States.

David Sirota

Brewster’s rally drew more than 4,000 people for a rousing refutation of Donald Trump. Should the district’s GOP House Representative Mike Lawler, up for reelection in November, w…

Joan Walsh

The president’s scatological No Kings post expresses the ugly emotion fueling his authoritarian rule.

Jeet Heer