rom the Greek wars chronicled by Thucydides in the 5th Century BCE to the nuclear brinkmanship of the 20th Century, power has been synonymous with ‘firepower;’ it was mostly measured in the number of battalions and the size of battleships.

“The strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must,” wrote the Greek historian, Thucydides in his magnum opus A History of the Peloponnesian War, describing a worldview that would shape the thinking of most power-wielders through millennia. Examining the world from the same lens as Thucydides did, the German-American jurist and political scientist, also known as the father of modern realism, offered a similar verdict “International Politics, like all other politics, is a struggle for power.”

The British Historian AJP Taylor,s who wrote and lectured extensively on military and war history, further narrowed the domain of power “The object of being a great power is to be able to fight a great war…” he theorised in his 1954 book The Struggle for Mastery in Europe 1848-1918. However, he also advised that the only way to remain a great power was “not to fight a war.”

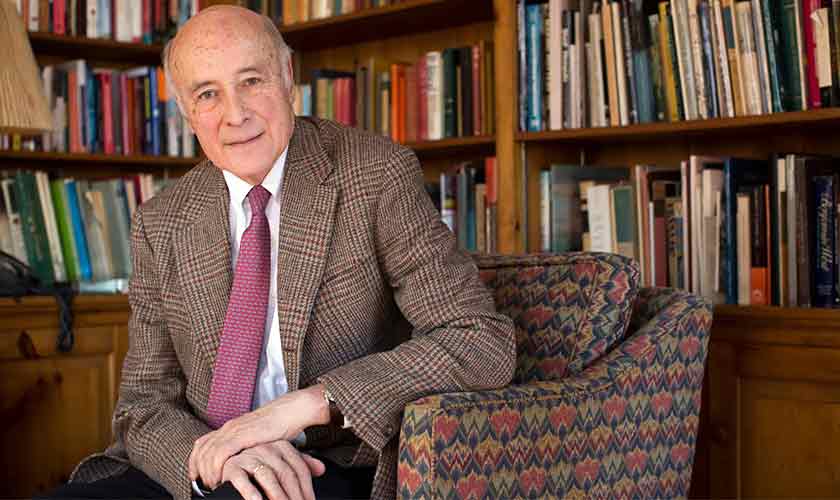

In the late 1980s, an American political scientist and professor at Harvard Kennedy School, Joseph S Nye Jr, was not convinced by the worldview held by these towering figures in the fields of history and politics. “Power is like weather. Everyone depends on it and talks about it, but few understand it,” wrote Nye, who, besides teaching at Harvard’s Kennedy School, served in key positions in the Carter and Clinton administrations, including the chairman of the National Intelligence Council from 1993 to ’94.

Nye was obsessed with exploring the softer and moral aspects of power. He spent the last 50 years of his life explaining it to the world through his books, articles and lectures.

In 1977, Nye collaborated with Robert O Keohane, a professor of political science at Stanford University, in authoring Power and Interdependence, a groundbreaking work that brought international political economy (IPE) into the fold of international relations (IR). The theory they presented was labelled as ‘neo-liberalism’ in the canon of IR. Nye, along with Keohane, criticised the ‘realist’ approach towards state relations and their belief that interstate relations are mostly characterised by distrust and competition. In response to the neo-realist notion of a zero-sum game, where they consider the gain of one state as the ultimate loss of another, Nye argued that besides security matters, states pursue mutually beneficial activities like trade or environmental protection. Besides states, Nye and Keohane included multinational corporations and intergovernmental Organisations as key actors in the global system.

Though Professor Nye wrote on numerous subjects, including the role of morality in global politics, nuclear ethics and the role of morality in political leadership, it was his theory of ‘soft power’ that made him famous around the world. Before delving into his soft power theory, it seems appropriate to shed some light on the context in which the theory emerged.

It was the final decade of the Cold War, and the American intelligentsia, particularly those specialising in global history and global politics, were locked in a fierce debate about the possible future of the American empire. “Whether the US will remain as powerful as it is? Will it even grow more powerful, or will it go down the path of other empires that have disappeared in the pages of history?” These questions gripped the imaginations of international relations scholars, dividing them into two groups. One group was dubbed as the ‘declinists’ because they saw the US going through the path of decline like that of Rome and Great Britain, while the other group, dubbed as ‘anti-declinists, optimists or resilienists’ consisted of scholars who saw the US role in the global system as transformative and resilient.

Meanwhile, Paul Kennedy, a British historian who was teaching at Yale entered the debate and put his long argument in the form of The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (1987). Kennedy imbibed on the five hundred years history of great powers from 1500 to 1980, scanning for the common elements that enabled the rise of empires and the possible reasons behind their decline. Kennedy found that military ‘over-stretch’ and imperial expansion had often caused the great powers to decline. While discussing the Pax Americana, Kennedy, though very cautiously and prudently, hinted that the American empire had reached its military ‘overstretch’ and may fall like its predecessors. Kennedy’s book became a hit, sparking a heated debate among the scholars and practitioners of global politics. You can imagine the popularity of his book from the fact that, according to a list of books released by the US government in 2015, a copy of The Rise and Fall of Great Powers was found on Osama’s bookshelf in his compound in Abbottabad.

“Power is like love — easier to experience than to define or measure it.”

Kennedy was not alone in holding this opinion, similar views were expressed by numerous scholars, collectively dubbed as the ‘declinists.’ Notable among them were: Robert Gilpin who, in his War and Change in World Politics (1981), theorised that hegemonic powers rise and fall in cycles and predicted a possible decline of US dominance. There was Immanuel Wallerstein, a Marxist structuralist who saw the US power tied to a capitalist world order, which was, according to Wallerstein, in terminal decline.

The most vocal and fierce, yet less popular, among the declinists was Chalmers Johnson- the American political sScientist and professor emeritus at the University of California, San Diego. Johnson’s famous critique of the American empire came in the form of a trilogy he wrote between 2000 and 2007. The first book in the trilogy was titled The Blowback (2000). In it he argued that American foreign intervention will have unintended consequences at home. Even though the book didn’t get much attention when it was first published in 2000, it was later hailed as ‘prophetic’ when the ‘blowback’ occurred in the form of the 9/11 attacks a year after he had mentioned the possibility.

In the second book of the trilogy, The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic (2004), Johnson surveyed the global expansion of the US military, counting over 700 overseas bases and criticised the growing militarisation of American society and foreign policy.

In his concluding volume of the trilogy titled Nemesis: The Last Days of the American Republic (2007), Johnson claimed that the US had become a ‘military empire’ incompatible with constitutional democracy. Drawing comparisons with historical empires like Rome, Johnson warned that unless the US renounced its obsession with military empire-building, its fate as a republic was doomed.

While the declinists attracted many fans and convinced many minds, Professor Nye wasn’t among them. Nye argued that the declinists are measuring power specifically in military hardware and economic output, which Nye later categorised as ‘hard-power.’ The declinists were missing a key point, according to Nye, as they didn’t consider the attraction of American culture, its Hollywood and Harvard; its Jazz and jeans; its Macdonalds and Microsoft; its TIME and The New York Times.

In 1990, Nye introduced his theory, first in an article published in the Foreign Policy magazine and then in a book titled Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power. As the title of the book suggests, it was a rebuttal of the declinists like Kennedy.

Nye defined power as “the ability to get what you want.” He mentioned three basic ways through which one can do that: a. coercion (sticks) b. payments (carrots), (both are forms of hard power) and c. attraction (soft power). In 2004, he presented a more detailed elaboration of his theory in Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics, where he clearly differentiated between hard (coercive) power and soft (attractive) power. In this book, Nye also introduced a third, hybrid form of power that he called smart power – that is a strategic combination of hard and soft power; knowing when to use persuasion, when to use force and when to calibrate the two. While hard power can force others to do what you want, Nye argued, soft power is the ability to make others want what you want, to shape their choices, preferences and desires.

Where does soft power come from? Nye mentioned three main sources of soft power: the country’s culture (where it is attractive to others), its political values (when it lives up to them at home and abroad) and its foreign policy (when it is seen by others as legitimate and having moral authority).

In the 2000s, the idea of soft power that Nye conceived of while “scribbling on the yellow pages of a notepad in his kitchen” had gone global. The concept of soft power was taken seriously by policymakers from Brussels to Beijing, and papers had started to pour in from academia applying Nye’s theory to various contexts.

In 2007, former Chinese president Hu Jintao told the 17th Communist Party Congress that China must “enhance culture as part of the soft power of our country.” Thus, China invested billions of dollars into establishing Confucious Institutes around the World, launching Global Broadcast Services and entering into aid diplomacy. Japan stepped in with its anime, fashion, cuisines and pop culture. South Korea strategically used its dramas, and K. pop to export national identity and Korean culture – a phenomenon dubbed as the “K-wave” or “Hallyu,” referring to the global popularity of Korean culture. India used its Bollywood, yoga, cricket and its diverse and influential diaspora to project its soft power abroad. There were Qatar, Dubai and Turkey, all competing to project a soft image of themselves and make others want what they want.

However, with the return of Donald Trump in the US and many hardliners around the world, Joseph Nye’s theory seems to be in retreat, ceding ground to the ‘realist’ worldview anticipated by Thucydides 3000 years ago.

For centuries, scholars have struggled to understand the nature and behaviour of power. So did Nye, who concluded: “Power is like love — easier to experience than to define or measure it.”

Joseph Nye died at the age of 88 on May 6, 2025.

The writer has a background in English literature, history and politics. He can be reached at [email protected].