So far, the U.S. has tapped only about 0.7 percent of its own geothermal potential, providing just 0.4 percent of the nation’s power.

By 2050, estimates suggest that the global geothermal industry could produce 6,000 terawatt-hours per year, or enough electricity to satisfy the current demands of the U.S. and India combined. So far, however, the U.S. has tapped only about 0.7 percent of its own geothermal potential, providing just 0.4 percent of the nation’s power. This is partly because federal clean energy policies have historically favored wind, solar, and battery manufacturing, industries that cost less to build and are easier to deploy.

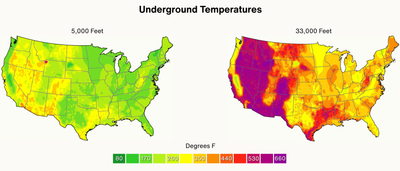

Geothermal is comparatively risky. It has so far been reliant on both naturally occurring water and extremely hot rocks in shallow, permeable reservoirs — a precise geologic cocktail usually confined to volcanically active Western states. Such locations can be tough to locate and even harder to drill down to. Boring through rock can be extremely expensive, as is running transmission lines to sites that tend to be built out in the desert.

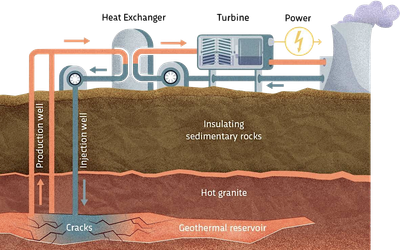

This is changing, however, thanks to a series of technological breakthroughs that began in 2013 with the first commercial enhanced geothermal system, or EGS. Heat is everywhere on Earth if you drill deep enough; but rather than searching for the ideal geothermal conditions, EGS creates them by injecting a pressurized fluid — primarily water — to fracture hot rocks and create a subsurface reservoir. The process borrows heavily from the oil industry’s experience fracking for natural gas in shale deposits. Today, “next-generation” geothermal technologies, led by the Department of Energy (DOE)’s FORGE program and companies including Fervo Energy, Sage Geosystems, XGS Energy, and Eavor, are taking the process even farther by drilling deeper and avoiding the need to fracture rocks altogether.

Enhanced Geothermal

Jeotermal Enerji

“What has changed is the ubiquitous aspect of this abundant energy source,” says Terra Rogers, a program director for the Clean Air Task Force.

Fervo Energy, based in Houston, is building the world’s largest example of this technology in the Utah desert, where engineers are boring down more than 15,000 feet, then continuing horizontally through rock that reaches 520 degrees F, pumping cold water into the hole, and bringing it up piping hot to spin a turbine. The company says the project will be completed sometime after 2028 and that it expects the system to generate 2 gigawatts of electricity, or about as much as the Hoover Dam.

This technology has been in the works for some time, but the industry got a recent shot in the arm from the incentives and tax breaks of President Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). More than 150 geothermal startups have been established since the bill was signed in 2022, and each is working toward extending the reach of what had been seen as a power source limited to a few states. Their success will require drilling deeper to hotter rocks, Rogers says, and already “we are seeing engineering feats that demonstrate that depths as great as [40,000 feet] are reasonable in the next 10 to 15 years.”

A major project outside the intermountain West and California could show that geothermal is no longer limited to volcanic hotspots.

Today, the U.S. generates about 4 megawatts of geothermal power, accounting for more than 20 percent of the world’s total geothermal production. The DOE predicts that EGS could push generation to 300 gigawatts by 2050 while lowering costs by some 90 percent to $45 per megawatt-hour by 2035, making it competitive with land-based wind power. As the technology matures, investors are jockeying for a piece of the emerging market.

“Geothermal hasn’t received the same level of financial support as things like hydrogen, carbon capture, or nuclear,” says Matt Mailloux, director of clean energy and permitting for the conservative energy think tank, ClearPath. “And even in the absence, we’ve seen tremendous results and corporate commitments to purchase geothermal uptake.”

Fervo’s commercial pilot project in Utah came online in late 2023 with help from Google, which first invested in the company in 2021 to secure clean power for some of its data centers. In April, Shell Energy committed to buying 31 megawatts of the company’s geothermal power for 15 years and supplying it to the grid beginning next year. Then, in June, Fervo raised an additional $244 million in new investment led by an Oklahoma-based oil company, which will help it complete its Utah project.

A drilling rig bores down more than 15,000 feet for a geothermal project in Beaver County, Utah.

Fervo Energy

But Fervo is not alone. XGS Energy, which is developing a way to generate power without significant water use, recently announced a partnership with Meta to power its data centers, in addition to homes in New Mexico. This would be the first major project outside the intermountain West and California, showing that geothermal is no longer limited to volcanic hotspots.

In February, the Defense Department announced that it was expediting the process to build geothermal power on U.S. military bases and included startups like XGS, alongside energy behemoths Baker Hughes and SLB, on a short list of companies it had pre-approved to bid on projects. For XGS, which has raised about $60 million in venture capital to date, these partnerships represent a critical step toward mainstream commercialization, even if its New Mexico project isn’t expected to supply the grid until 2030.

“We’ve got strong market demand, strong financial support, strong community support to do these projects,” says Lucy Darago, chief commercial officer for XGS, “but we’re not yet at a stage of maturity where a bank would look at us and say it feels confident underwriting this project.”

Since the start of 2025, at least $15.5 billion in clean energy projects and factories have been cancelled or downsized, and 12,000 jobs lost.

The DOE suggested in a 2024 report that this “commercial liftoff” could happen once the industry has built 10 power-generating facilities in diverse geological conditions using $5 billion in public and private funding. That investment was on track thanks to the IRA, and the speed at which the industry ramps up now hinges on the outcome of the reconciliation discussions now underway in Congress.

In its draft of Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act, the House proposed quickly dismantling, among other things, some $740 billion of IRA tax credits for clean energy projects, including geothermal. Facing what would be a serious blow for an industry that’s finally picking up momentum, geothermal leaders and advocates are lobbying to keep the tax credits and are finding support from the GOP.

Republican lawmakers from states with untapped geothermal potential and strong links to the fossil fuel industry, including Senator John Curtis, of Utah, have called for maintaining protections for geothermal in the reconciliation bill.

Source: Blackwell et al.

SMU Geothermal Laboratory / Adapted by Yale Environment 360

“We simply cannot afford to treat good policy ideas as guilty by political association,” Curtis wrote in a recent op-ed. “Businesses from across the energy spectrum — oil and gas, nuclear, renewables — have already made billions in long-term investments based on these policies.”

The uncertain fate of the country’s clean energy programs has already led some investors to pull up stakes: Since the start of 2025, at least $15.5 billion in clean energy projects and factories have been cancelled or downsized, and 12,000 jobs were lost, according to a report from E2, a nonpartisan advocacy and research group. And Republican-dominated districts saw the worst of it, losing more than $6 billion of investment and more than 10,000 jobs. However, the only geothermal project that stuttered during that time was the Black Rock Geothermal Project, at the Salton Sea, which was suspended due to prolonged regulatory delays and transmission hurdles.

GOP lawmakers, including John Hoeven of North Dakota and Nick Begich of Alaska, have praised geothermal as a source of baseload power — the minimum consistent supply needed to keep the lights on day and night, regardless of weather or foreign wars.

For geothermal startups, investment from oil companies can help overcome the enormous upfront cost of development.

During the reconciliation debates, conservatives have also argued that government support should be reserved for new technologies to prove they work and can be scaled up. “The opportunity here is to help technologies like nuclear and geothermal stand on their own two feet,” ClearPath’s Mailloux says. The sense among the GOP is that wind and solar have matured enough to do that.

Geothermal’s direct links with and support from the fossil fuel industry have made it a comparatively palatable renewable option for an administration that has shown antipathy for other forms of clean energy. Geothermal uses natural gas drilling technology; it offers opportunities for fossil fuel workers and manufacturers, as well as a new source of revenue for fossil fuel energy producers; and it is often developed in red states and rural communities. This overlap has been crucial to winning support from Republican lawmakers in oil-rich districts who receive campaign donations from oil companies and consider anything that boosts that industry a win for national security.

Multinational drilling conglomerates like Shell, Halliburton, Baker Hughes, SLB, and Chevron are investing in geothermal startups and starting their own geothermal projects. Halliburton sponsored a recent lobbying push in Washington after the House released its draft of the reconciliation bill that would have axed tax incentives for geothermal. For these big companies, geothermal is a logical next step. For the geothermal startups, oil money can help overcome the enormous upfront cost of development, which is three to six times more expensive than starting an offshore wind farm. Both the startups and deep-pocketed investors were depending on the IRA’s incentives to help the next generation of geothermal technologies pencil out, just as federal tax incentives had done for the shalefracking boom in the 1980s.

An enhanced geothermal plant near Winnemucca, Nevada, generates power for Google data centers.

Google

If the IRA’s tax incentives disappear, “it wouldn’t kill the geothermal industry in the U.S., but it would halt certain projects from going forward,” says Katrina McLaughlin, a World Resources Institute researcher. And that would mean a slower path towards commercial viability.

Still, the technological advancements, the surge of recent investments, and the dire need to get more power online make McLaughlin confident that geothermal will move forward. “There have been other periods where it seemed like it was on the cusp of a big breakthrough,” she says, “I do think that it feels a little bit different this time.”

Regardless of the outcome of the reconciliation bill, Republican lawmakers in both the House and Senate have backed and sponsored separate bills that could help the geothermal industry by streamlining the permitting process for drilling and shortening environmental review timelines. These reforms would greatly improve investor confidence, industry analysts say, but financing remains the major barrier.

Although the U.S. has an edge in the geothermal space, there are growing concerns that a lack of funding could send innovation elsewhere. In May, the Canada-based startup Eavor announced that it had shortened a drilling process that used to take days down to minutes. The company is building a novel 8.2-megawatt geothermal power plant and heating system in Bavaria with support from European investors and the EU Innovation Fund. It could begin producing power this year. Advocates of the technology suggest that if Congress does not protect the sector’s incentives, the biggest loser won’t be the geothermal industry overall, but the geothermal industry in the U.S.